The Great Caliban

The Struggle Against the Rebel Body

Life is but a motion of limbs.... For what is the heart, but a spring; and the nerves, but so many strings; and the joints but so many wheels, giving motion to the whole body.

(Hobbes, Leviathan, 1650)

Yet I will be a more noble creature, and at the very time when my natural necessities debase me into the condition of the Beast, my Spirit shall rise and soar and fly up towards the employment of the angels.

(Cotton Mather, Diary, 1680-1708)

...take some Pity on me... for my Friends is very Poor, and my Mother is very sick, and I am to die next Wednesday Morning, so I hope you will be so good as to give my Friends a small Trifill of Money to pay for a Coffin and a Sroud, for to take my body a way from the Tree in that I am to die on... and dont be faint Hearted... so I hope you will take it into Consideration of my poor Body, consedar if it was your own Cace, you would be willing to have your Body saved from the Surgeons.

(Letter of Richard Tobin, condemned to death in London in 1739)

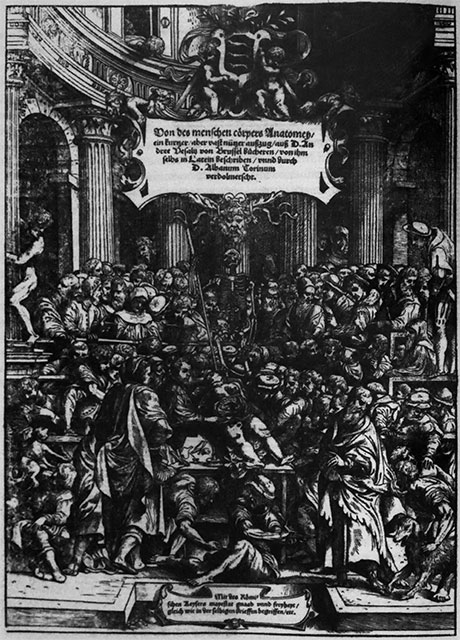

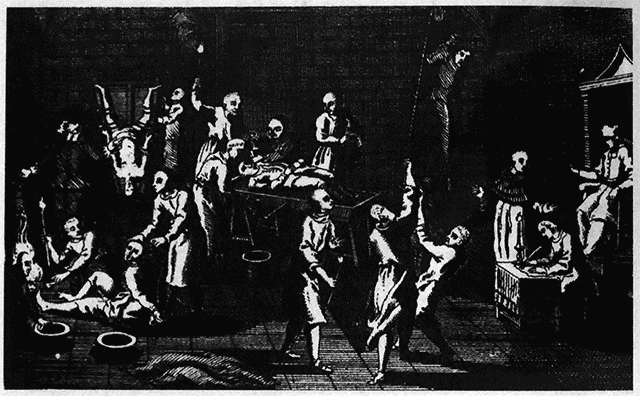

Title page of Andreas Vesalius' De Humani Corporis Fabrica (padua, 1543). The triumph of the male, upper class, patriarchal order through the constitution of the new anatomical theatre could not be more complete. Of the woman dissected and delivered to the public gaze, the author tells us that "in fear of being hanged [she] had declared herself pregnant," but after it was discovered that she was not, she was hung. The female figure in the back (perhaps a prostitute or a midwife) lowers her eyes, possibly ashamed in front of the obscenity of the scene and its implicit violence.

One of the preconditions for capitalist development was the process that Michel Foucault defined as the "disciplining of the body," which in my view consisted of an attempt by state and church to transform the individual's powers into labor-power. This chapter examines how this process was conceived and mediated in the philosophical debates of the time, and the strategic interventions which it generated.

It was in the 16th century, in the areas of Western Europe most affected by the Protestant Reformation and the rise of the mercantile bourgeoisie, that we see emerging in every field — the stage, the pulpit, the political and philosophical imagination — a new concept of the person. Its most ideal embodiment is the Shakespearean Prospero of the The Tempest (1612), who combines the celestial spirituality of Ariel and the brutish materiality of Caliban. Yet he betrays an anxiety over the equilibrium achieved that rules out any pride for "Man's" unique position in the Great Chain of Being.1 In defeating Caliban, Prospero must admit that "this thing of darkeness is mine," thus reminding his audience that our human partaking of the angel and the beast is problematic indeed.

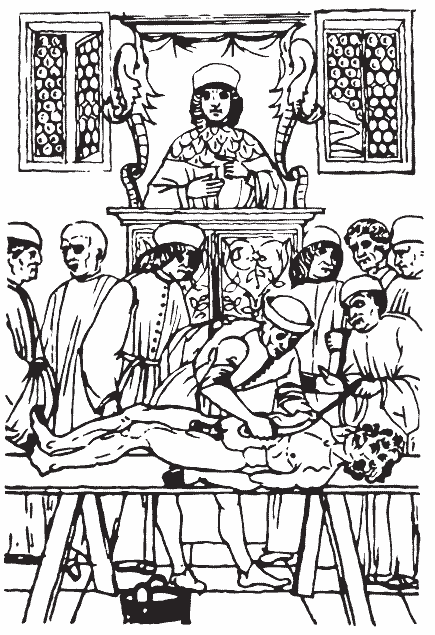

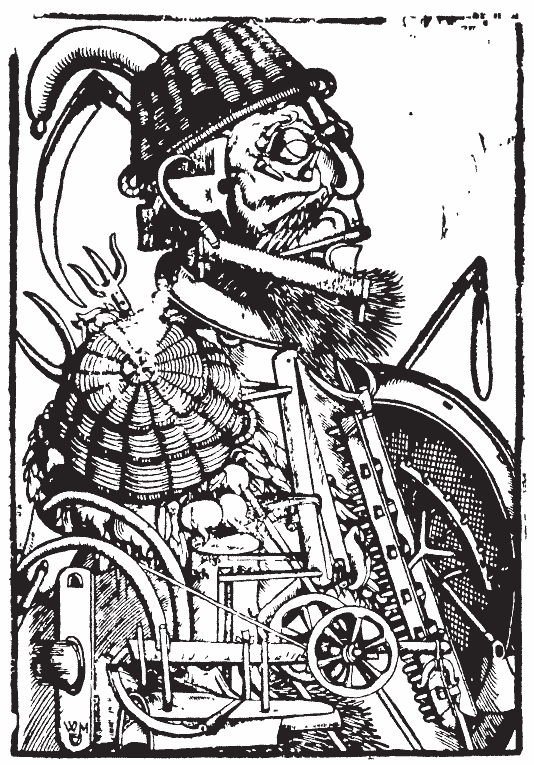

15th century woodcut, "The devil's assault on the dying man is a theme that pervades all the [medieval] popular tradition." (From Alfonso M. di Nola, 1987.)

In the 17th century, what in Prospero remains a subliminal foreboding is formalized as the conflict between Reason and the Passions of the Body, which reconceptualizes classic Judeo-Christian themes to produce a new anthropological paradigm. The outcome is reminiscent of the medieval skirmishes between angels and devils for the possession of the departing soul. But the conflict is now staged within the person who is reconstructed as a battlefield, where opposite elements clash for domination. On the one side, there are the "forces of Reason": parsimony, prudence, sense of responsibility.; self-control. On the other, the "low instincts of the Body": lewdness, idleness, systematic dissipation of ones vital energies. The battle is fought on many fronts because Reason must be vigilant against the attacks of the carnal self, and prevent "the wisdom of the flesh" (in Luther's words) from corrupting the powers of the mind. In the extreme case, the person becomes a terrain for a war of all against all:

Let me be nothing, if within the compass of my self I do not find the battail of Lepanto: Passions against Reason, Reason against Faith, Faith against the Devil, and my Conscience against all.

(Thomas Browne 1928: 76)

In the course of this process a change occurs in the metaphorical field, as the philosophical representation of individual psychology borrows images from the body-politics of the state, disclosing a landscape inhabited by "rulers" and "rebellious subjects," "multitudes" and "seditions," "chains" and "imperious commands" and (with Thomas Browne) even the executioner (ibid.: 72).2 As we shall see, this conflict between Reason and the Body, described by the philosophers as a riotous confrontation between the "better" and the "lower sorts," cannot be ascribed only to the baroque taste for the figurative, later to be purged in favor of a "more masculine" language.3 The battle which the 17th-century discourse on the person imagines unfolding in the microcosm of the individual has arguably a foundation in the reality of the time. It is an aspect of that broader process of social reformation, whereby, in the "Age of Reason," the rising bourgeoisie attempted to remold the subordinate classes in conformity with the needs of the developing capitalist economy.

It was in the attempt to form a new type of individual that the bourgeoisie engaged in that battle against the body that has become its historic mark. According to Max Weber, the reform of the body is at the core of the bourgeois ethic because capitalism makes acquisition "the ultimate purpose of life," instead of treating it as a means for the satisfaction of our needs; thus, it requires that we forfeit all spontaneous enjoyment of life (Weber 1958: 53). Capitalism also attempts to overcome our "natural state," by breaking the barriers of nature and by lengthening the working day beyond the limits set by the sun, the seasonal cycles, and the body itself, as constituted in pre-industrial society.

Marx, too, sees the alienation from the body as a distinguishing trait of the capitalist work-relation. By transforming labor into a commodity, capitalism causes workers to submit their activity to an external order over which they have no control and with which they cannot identify. Thus, the labor process becomes a ground of selfestrangement: the worker "only feels himself outside his work, and in his work feels outside himself. He is at home when he is not working and when he is working is not at home" (Marx 1961:72). Furthermore, with the development of a capitalist economy, the worker becomes (though only formally) the "free owner" of "his" labor-power, which (unlike the slave) he can place at the disposal of the buyer for a limited period of time. This implies that "[h]e must constantly look upon his labour-power" (his energies, his faculties) "as his own property, his own commodity" (Marx 1906,Vol. 1:186).4 This too leads to a sense of dissociation from the body, which becomes reified, reduced to an object with which the person ceases to be immediately identified.

The image of a worker freely alienating his labor, or confronting his body as capital to be delivered to the highest bidder, refers to a working class already molded by the capitalist work-discipline. But only in the second half of the 19th century can we glimpse that type of worker — temperate, prudent, responsible, proud to possess a watch (Thompson 1964), and capable of looking upon the imposed conditions of the capitalist mode of production as "self-evident laws of nature" (Marx 1909, Vol. 1:809) — that personifies the capitalist utopia and is the point of reference for Marx.

The situation was radically different in the period of primitive accumulation when the emerging bourgeoisie discovered that the "liberation of labor-power" — that is, the expropriation of the peasantry from the common lands — was not sufficient to force the dispossessed proletarians to accept wage-labor. Unlike Milton's Adam, who, upon being expelled from the Garden of Eden, set forth cheerfully for a life dedicated to work,5 the expropriated peasants and artisans did not peacefully agree to work for a wage. More often they became beggars, vagabonds or criminals. A long process would be required to produce a disciplined work-force. In the 16th and 17th centuries, the hatred for wage-labor was so intense that many proletarians preferred to risk the gallows, rather than submit to the new conditions of work (Hill 1975:219—39).6

Woman selling rags and vagabond. The expropriated peasants and artisans did not peacefully agree to work for a wage. More often they became beggars, vagabonds or criminals. Design by Louis-Leopold Boilly (1761-1845).

This was the first capitalist crisis, one far more serious than all the commercial crises that threatened the foundations of the capitalist system in the first phase of its development.7 As is well-known, the response of the bourgeoisie was the institution of a true regime of terror, implemented through the intensification of penalties (particularly those punishing the crimes against property), the introduction of "bloody laws" against vagabonds, intended to bind workers to the jobs imposed on them, as once the serfs had been bound to the land, and the multiplication of executions. In England alone, 72,000 people were hung by Henry the VIII during the thirty-eight years of his reign; and the massacre continued into the late 16th century. In the 1570s, 300 to 400 "rogues" were "devoured by the gallows in one place or another every year" (Hoskins 1977: 9; Holinshed, 1577). In Devon alone, seventy-four people were hanged just in 1598 (ibid.).

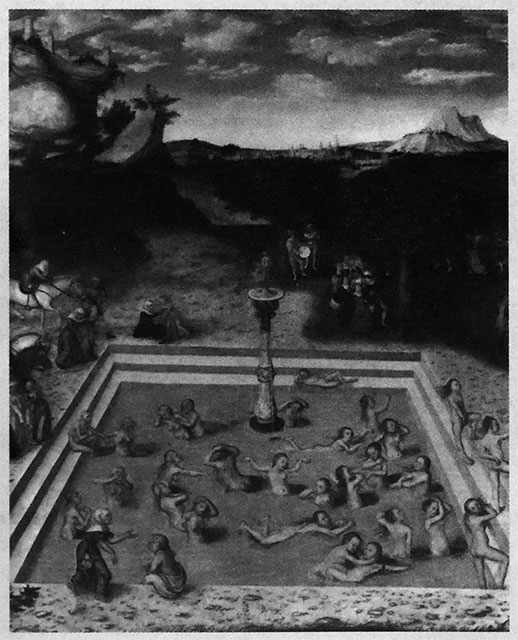

But the violence of the ruling class was not confined to the repression of transgressors. It also aimed at a radical transformation of the person, intended to eradicate in the proletariat any form of behavior not conducive to the imposition of a stricter work-discipline. The dimensions of this attack are apparent in the social legislation that, by the middle of the 16th century, was introduced in England and France. Games were forbidden, particularly games of chance that, besides being useless, undermined the individual's sense of responsibility and "work ethic." Taverns were closed, along with public baths.

Nakedness was penalized, as were many other "unproductive" forms of sexuality and sociality. It was forbidden to drink, swear, curse.8

It was in the course of this vast process of social engineering that a new concept of the body and a new policy toward it began to be shaped. The novelty was that the body was attacked as the source of all evils, and yet it was studied with the same passion that, in the same years, animated the investigation of celestial motion.

Why was the body so central to state politics and intellectual discourse? One is tempted to answer that this obsession with the body reflects the fear that the proletariat inspired in the ruling class.9 It was the fear felt by the bourgeois or the nobleman alike who, wherever they went, in the streets or on their travels, were besieged by a threatening crowd, begging them or preparing to rob them. It was also the fear felt by those who presided over the administration of the state, whose consolidation was continuously undermined — but also determined — by the threat of riots and social disorders.

Yet, there was more. We must not forget that the beggarly and riotous proletariat — who forced the rich to travel by carriage to escape its assaults, or to go to bed with two pistols under the pillow — was the same social subject who increasingly appeared as the source of all wealth. It was the same of whom the mercantilists, the first economists of capitalist society, never tired of repeating (though not without second thoughts) that "the more the better," often deploring that so many bodies were wasted on the gallows.10

Many decades were to pass before the concept of the value of labor entered the pantheon of economic thought. But that work ("industry"), more than land or any other "natural wealth," is the primary source of accumulation was a truth well understood at a time when the low level of technological development made human beings the most important productive resource. As Thomas Mun (the son of a London merchant and spokesman for the mercantilist position) put it:

.. .we know that our own natural wares do not yield us so much profit as our industry....For Iron in the Mines is of no great worth, when it is compared with the employment and advantage it yields being digged, tried, transported, bought, sold, cast into Ordnance, Muskets....wrought into Anchors, bolts, spikes, nails and the like, for the use of Ships, Houses, Carts, Coaches, Ploughs, and other instruments for Tillage.

(Abbott 1946:2)

Even Shakespeare's Prospero insists on this crucial economic fact in a little speech on the value of labor, which he delivers to Miranda after she manifests her utter disgust with Caliban:

But, as ‘tis

We cannot miss him. He does make our fire Fetch in our wood, and serves in office

That profit us.

(The Tempest, Act I, Scene 2)

The body, then, came to the foreground of social policies because it appeared not only as a beast inert to the stimuli of work, but also as the container of labor-power, a means of production, the primary work-machine. This is why, in the strategies adopted by the state towards it, we find much violence, but also much interest; and the study of bodily motions and properties becomes the starting point for most of the theoretical speculation of the age — whether aiming, with Descartes, to assert the immortality of the soul, or to investigate, with Hobbes, the premises of social governability.

Indeed, one of the central concerns of the new Mechanical Philosophy was the mechanics of the body; whose constitutive elements — from the circulation of the blood to the dynamics of speech, from the effects of sensations to voluntary and involuntary motions — were taken apart and classified in all their components and possibilities. Descartes Treatise of Man (published in 1664)11 is a true anatomical handbook, though the anatomy it performs is as much psychological as physical. A basic task of Descartes' enterprise is to institute an ontological divide between a purely mental and a purely physical domain. Every manner, attitude, and sensation is thus defined; their limits are marked, their possibilities weighed with such a thoroughness that one has the impression that the "book of human nature" has been opened for the first time or, more likely, that a new land has been discovered and the conquistadors are setting out to chart its paths, compile the list of its natural resources, assess its advantages and disadvantages.

In this, Hobbes and Descartes were representatives of their time. The care they display in exploring the details of corporeal and psychological reality reappears in the Puritan analysis of inclinations and individual talents,12 which was the beginning of a bourgeois psychology, explicitly studying, in this case, all human faculties from the viewpoint of their potential for work and contribution to discipline. A further sign of a new curiosity about the body and "of a change in manners and customs from former times whereby the body can be opened" (in the words of a 17th-century physician) was also the development of anatomy as a scientific discipline, following its long relegation to the intellectual underground in the Middle Ages (Wightman 1972:90-92; Galzigna 1978).

The anatomy lesson at the University of Padova. The anatomy theatre disclosed to the public eye a disenchanted desecreated body. In De Fasciculo de Medicina. Venezia (1494).

But while the body emerged as the main protagonist in the philosophical and medical scenes, a striking feature of these investigations is the degraded conception they formed of it. The anatomy "theatre"13 discloses to the public eye a disenchanted, desecrated body, which only in principle can be conceived as the site of the soul, but actually is treated as a separate reality (Galzigna 1978:163—64).14 To the eye of the anatomist the body is a factory, as shown by the title that Andreas Vesalius gave to his epochal work on the "dissecting industry": De humani corporis fabrica (1543). In Mechanical Philosophy, the body is described by analogy with the machine, often with emphasis on its inertia. The body is conceived as brute matter, wholly divorced from any rational qualities: it does not know, does not want, does not feel. The body is a pure "collection of members" Descartes claims in his 1634 Discourse on Method (1973,Vol. I, 152). He is echoed by Nicholas Malebranche who, in the Dialogues on Metaphysics and on Religion (1688), raises the crucial question "Can a body think?" to promptly answer, "No, beyond a doubt, for all the modifications of such an extension consist only in certain relations of distance; and it is obvious that such relations are not perceptions, reasonings, pleasures, desires, feelings, in a word, thoughts" (Popkin 1966: 280). For Hobbes, as well, the body is a conglomerate of mechanical motions that, lacking autonomous power, operates on the basis of an external causation, in a play of attractions and aversions where everything is regulated as in an automaton (Leviathan Part I, Chapter VI).

It is true, however, of Mechanical Philosophy what Michel Foucault maintains with regard to the 17th and l8th-century social disciplines (Foucault 1977:137). Here, too, we find a different perspective from that of medieval asceticism, where the degradation of the body had a purely negative function, seeking to establish the temporal and illusory nature of earthly pleasures and consequently the need to renounce the body itself.

In Mechanical Philosophy we perceive a new bourgeois spirit that calculates, classifies, makes distinctions, and degrades the body only in order to rationalize its faculties, aiming not just at intensifying its subjection but at maximizing its social utility (Ibid.: 137—38). Far from renouncing the body, mechanical theorists seek to conceptualize it in ways that make its operations intelligible and controllable. Thus the sense of pride (rather than commiseration) with which Descartes insists that "this machine" (as he persistently calls the body in the Treatise of Man) is just an automaton, and its death is no more to be mourned than the breaking of a tool.15

Certainly, neither Hobbes nor Descartes spent many words on economic matters, and it would be absurd to read into their philosophies the everyday concerns of the English or Dutch merchants. Yet, we cannot fail to see the important contribution which their speculations on human nature gave to the emerging capitalist science of work. To pose the body as mechanical matter, void of any intrinsic teleology — the "occult virtues" attributed to it by both Natural Magic and the popular superstitions of the time — was to make intelligible the possibility of subordinating it to a work process that increasingly relied on uniform and predictable forms of behavior.

Once its devices were deconstructed and it was itself reduced to a tool, the body could be opened to an infinite manipulation of its powers and possibilities. One could investigate the vices and limits of imagination, the virtues of habit, the uses of fear, how certain passions can be avoided or neutralized, and how they can be more rationally utilized. In this sense, Mechanical Philosophy contributed to increasing the ruling-class control over the natural world, control over human nature being the first, most indispensable step. Just as nature, reduced to a "Great Machine," could be conquered and (in Bacon's words) "penetrated in all her secrets," likewise the body, emptied of its occult forces, could be "caught in a system of subjection," whereby its behavior could be calculated, organized, technically thought and invested of power relations" (Foucault 1977:26).

In Descartes, body and nature are identified, for both are made of the same particles and act in obedience to uniform physical laws set in motion by God's will. Thus, not only is the Cartesian body pauperized and expropriated from any magical virtue; in the great ontological divide which Descartes institutes between the essence of humanity and its accidental conditions, the body is divorced from the person, it is literally dehumanized. "I am not this body" Descartes insists throughout his Meditations (1641). And, indeed, in his philosophy the body joins a continuum of clock-like matter that the unfettered will can now contemplate as the object of its domination.

As we will see, Descartes and Hobbes express two different projects with respect to corporeal reality. In Descartes, the reduction of the body to mechanical matter allows for the development of mechanisms of self-management that make the body the subject of the will. In Hobbes, by contrast, the mechanization of the body justifies the total submission of the individual to the power of the state. In both, however, the outcome is a redefinition of bodily attributes that makes the body, ideally, at least, suited for the regularity and automatism demanded by the capitalist work-discipline.16 I emphasize "ideally" because, in the years in which Descartes and Hobbes were writing their treatises, the ruling class had to confront a corporeality that was far different from that appearing in their prefigurations.

It is difficult, in fact, to reconcile the insubordinate bodies that haunt the social literature of the "Iron Century" with the clock-like images by which the body is represented in Descartes' and Hobbes' works. Yet, though seemingly removed from the daily affairs of the class struggle, it is in the speculations of the two philosophers that we find first conceptualized the development of the body into a work-machine, one of the main tasks of primitive accumulation. When, for example, Hobbes declares that "the heart (is) but a spring... and the joints so many wheels," we perceive in his words a bourgeois spirit, whereby not only is work the condition and motive of existence of the body, but the need is felt to transform all bodily powers into work powers.

This project is a clue to understanding why so much of the philosophical and religious speculation of the 16th and 17th centuries consists of a true vivisection of the human body, whereby it was decided which of its properties could live and which, instead, had to die. It was a social alchemy that did not turn base metals into gold, but bodily powers into work-powers. For the same relation that capitalism introduced between land and work was also beginning to command the relation between the body and labor. While labor was beginning to appear as a dynamic force infinitely capable of development, the body was seen as inert, sterile matter that only the will could move, in a condition similar to that which Newton's physics established between mass and motion, where the mass tends to inertia unless a force is applied to it. Like the land, the body had to be cultivated and first of all broken up, so that it could relinquish its hidden treasures. For while the body is the condition of the existence of labor-power, it is also its limit, as the main element of resistance to its expenditure. It was not sufficient, then, to decide that in itself the body had no value. The body had to die so that labor-power could live.

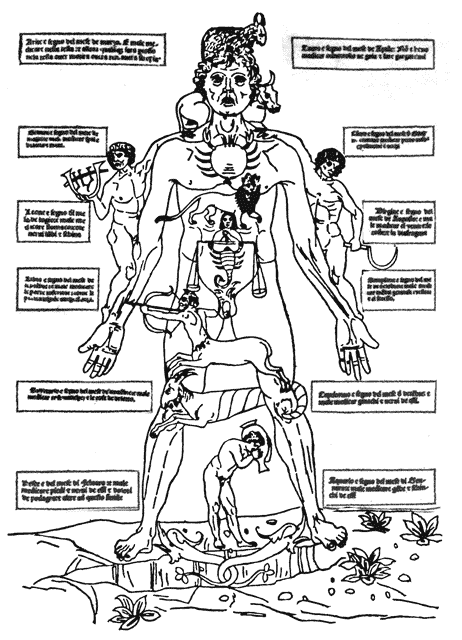

The conception of the body as a receptacle of magical powers largely derived from the belief in a correspondence between the microcosm of the individual and the macrocosm of the celestial workd, as illustrated in this 16th-century image of the "zodiacal man."

What died was the concept of the body as a receptacle of magical powers that had prevailed in the medieval world. In reality, it was destroyed. For in the background of the new philosophy we find a vast initiative by the state, whereby what the philosophers classified as "irrational" was branded as crime. This state intervention was the necessary "subtext" of Mechanical Philosophy. "Knowledge" can only become "power" if it can enforce its prescriptions. This means that the mechanical body, the body-machine, could not have become a model of social behavior without the destruction by the state of a vast range of pre-capitalist beliefs, practices, and social subjects whose existence contradicted the regularization of corporeal behavior promised by Mechanical Philosophy. This is why, at the peak of the "Age of Reason" — the age of scepticism and methodical doubt — we have a ferocious attack on the body, well-supported by many who subscribed to the new doctrine.

This is how we must read the attack against witchcraft and against that magical view of the world which, despite the efforts of the Church, had continued to prevail on a popular level through the Middle Ages. At the basis of magic was an animistic conception of nature that did not admit to any separation between matter and spirit, and thus imagined the cosmos as a living organism, populated by occult forces, where every element was in "sympathetic" relation with the rest. In this perspective, where nature was viewed as a universe of signs and signatures, marking invisible affinities that had to be deciphered (Foucault 1970:26-27), every element — herbs, plants, metals, and most of all the human body — hid virtues and powers peculiar to it. Thus, a variety of practices were designed to appropriate the secrets of nature and bend its powers to the human will. From palmistry to divination, from the use of charms to sympathetic healing, magic opened a vast number of possibilities. There was magic designed to win card games, to play unknown instruments, to become invisible, to win somebody's love, to gain immunity in war, to make children sleep (Thomas 1971; Wilson 2000).

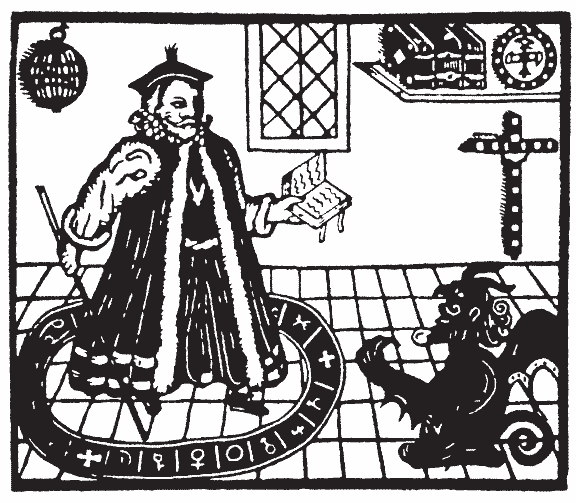

Frontispiece to the first edition of Christopher Marlowe's Doctor Faustus (1604), picturing the magician conjuring the Devil from the protected space of his magical circle.

Eradicating these practices was a necessary condition for the capitalist rationalization of work, since magic appeared as an illicit form of power and an instrument to obtain what one wanted without work, that is, a refusal of work in action. "Magic kills industry," lamented Francis Bacon, admitting that nothing repelled him so much as the assumption that one could obtain results with a few idle expedients, rather than with the sweat of one's brow (Bacon 1870:381).

Magic, moreover, rested upon a qualitative conception of space and time that precluded a regularization of the labor process. How could the new entrepreneurs impose regular work patterns on a proletariat anchored in the belief that there are lucky and unlucky days, that is, days on which one can travel and others on which one should not move from home, days on which to marry and others on which every enterprise should be cautiously avoided? Equally incompatible with the capitalist work-discipline was a conception of the cosmos that attributed special powers to the individual: the magnetic look, the power to make oneself invisible, to leave one's body, to chain the will of others by magical incantations.

It would not be fruitful to investigate whether these powers were real or imaginary. It can be said that all precapitalist societies have believed in them and, in recent times, we have witnessed a revaluation of practices that, at the time we refer to, would have been condemned as witchcraft. Let us mention the growing interest in parapsychology and biofeedback practices that are increasingly applied even by mainstream medicine. The revival of magical beliefs is possible today because it no longer represents a social threat. The mechanization of the body is so constitutive of the individual that, at least in industrialized countries, giving space to the belief in occult forces does not jeopardize the regularity of social behavior. Astrology too can be allowed to return, with the certainty that even the most devoted consumer of astral charts will automatically consult the watch before going to work.

However, this was not an option for the 17th-century ruling class which, in this initial and experimental phase of capitalist development, had not yet achieved the social control necessary to neutralize the practice of magic, nor could they functionally integrate magic into the organization of social life. From their viewpoint it hardly mattered whether the powers that people claimed to have, or aspired to have, were real or not, for the very existence of magical beliefs was a source of social insubordination.

Take, for example, the widespread belief in the possibility of finding hidden treasures by the help of magical charms (Thomas 1971:234-37). This was certainly an impediment to the institution of a rigorous and spontaneously accepted work-discipline. Equally threatening was the use that the lower classes made of prophecies, which, particularly during the English Civil War (as already in the Middle Ages), served to formulate a program of struggle (Elton 1972:142ff). Prophecies are not simply the expression of a fatalistic resignation. Historically they have been a means by which the "poor" have externalized their desires, given legitimacy to their plans, and have been spurred to action. Hobbes recognized this when he warned that "There is nothing that... so well directs men in their deliberations, as the foresight of the sequels of their actions; prophecy being many times the principal cause of the events foretold" (Hobbes, "Behemot," Works VI: 399).

But regardless of the dangers which magic posed, the bourgeoisie had to combat its power because it undermined the principle of individual responsibility, as magic placed the determinants of social action in the realm of the stars, out of their reach and control. Thus, in the rationalization of space and time that characterized the philosophical speculation of the 16th and 17th centuries, prophecy was replaced with the calculation of probabilities whose advantage, from a capitalist viewpoint, is that here the future can be anticipated only insofar as the regularity and immutability of the system is assumed; that is, only insofar as it is assumed that the future will be like the past, and no major change, no revolution, will upset the coordinates of individual decision-making. Similarly, the bourgeoisie had to combat the assumption that it is possible to be in two places at the same time, for the fixation of the body in space and time, that is, the individual's spatio-temporal identification, is an essential condition for the regularity of the work-process.17

The incompatibility of magic with the capitalist work-discipline and the requirement of social control is one of the reasons why a campaign of terror was launched against it by the state — a terror applauded without reservations by many who are presently considered among the founders of scientific rationalism: Jean Bodin, Mersenne, the mechanical philosopher and member of the Royal Society Richard Boyle, and Newton's teacher, Isaac Barrow.18 Even the materialist Hobbes, while keeping his distance, gave his approval. "As for witches," he wrote, "I think not that their witchcraft is any real power; but yet that they are justly punished, for the false belief they have that they can do such mischief, joined with their purpose to do it if they can" (Leviathan 1963; 67). He added that if these superstitions were eliminated, "men would be much more fitted than they are for civil obedience" (ibid.), Hobbes was well advised. The stakes on which witches and other practitioners of magic died, and the chambers in which their tortures were executed, were a laboratory in which much social discipline was sedimented, and much knowledge about the body was gained. Here those irrationalities were eliminated that stood in the way of the transformation of the individual and social body into a set of predictable and controllable mechanisms. And it was here again that the scientific use of torture was born, for blood and torture were necessary to "breed an animal" capable of regular, homogeneous, and uniform behavior, indelibly marked with the memory of the new rules (Nietzsche 1965:189—90).

The torture chamber. 1809 engraving by Manet in Joseph Lavallee, Histories des Inquisitions Religieuses d'Italie, d'Espagne et de Portugal.

A significant element in this context was the condemnation as maleficium of abortion and contraception, which consigned the female body — the uterus reduced to a machine for the reproduction of labor — into the hands of the state and the medical profession. I will return later to this point, in the chapter on the witch-hunt, where I argue that the persecution of the witches was the climax of the state intervention against the proletarian body in the modern era.

Here let us stress that despite the violence deployed by the state, the disciplining of the proletariat proceeded slowly throughout the 17th century and into the 18th century in the face of a strong resistance that not even the fear of execution could overcome. An emblematic example of this resistance is analyzed by Peter Linebaugh in "The Tyburn Riots Against the Surgeons." Linebaugh reports that in early l8th -century London, at the time of an execution, a battle was fought by the friends and relatives of the condemned to prevent the assistants of the surgeons from seizing the corpse for use in anatomical studies (Linebaugh 1975). This battle was fierce, because the fear of being dissected was no less than the fear of death. Dissection eliminated the possibility that the condemned might revive after a poorly executed hanging, as often occurred in 18th-century England (ibid.: 102-04). A magical conception of the body was spread among the people according to which the body continued to live after death, and by death was enriched with new powers. It was believed that the dead possessed the power to "come back again" and exact their last revenge upon the living. It was also believed that a corpse had healing virtues, so that crowds of sick people gathered around the gallows, expecting from the limbs of the dead effects as miraculous as those attributed to the touch of the king (ibid.: 109-10).

Dissection thus appeared as a further infamy, a second and greater death, and the condemned spent their last days making sure that their body should not be abandoned into the hands of surgeons. This battle, significantly occurring at the foot of the gallows, demonstrates both the violence that presided over the scientific rationalization of the world, and the clash of two opposite concepts of the body, two opposite investments in it. On one side, we have a concept of the body that sees it endowed with powers even after death; the corpse does not inspire repulsion, and is not treated as something rotten or irreducibly alien. On the other, the body is seen as dead even when still alive, insofar as it is conceived as a mechanical device, to be taken apart just like any machine. "At the gallows, standing at the conjunction of the Tyburn and Edgware roads," Peter Linebaugh writes, "we find that the history of the London poor and the history of English science intersect." This was not a coincidence; nor was it a coincidence that the progress of anatomy depended on the ability of the surgeons to snatch the bodies of the hanged at Tyburn.19 The course of scientific rationalization was intimately connected to the attempt by the state to impose its control over an unwilling workforce.

This attempt was even more important, as a determinant of new attitudes towards the body, than the development of technology. As David Dickson argues, connecting the new scientific worldview to the increasing mechanization of production can only hold as a metaphor (Dickson 1979: 24). Certainly, the clock and the automated devices that so much intrigued Descartes and his contemporaries (e.g. hydraulically moved statues), provided models for the new science, and for the speculations of Mechanical Philosophy on the movements of the body. It is also true that starting from the 17th century, anatomical analogies were drawn from the workshops of the manufacturers: the arms were viewed as levers, the heart as a pump, the lungs as bellows, the eyes as lenses, the fist as a hammer (Mumford 1962:32). But these mechanical metaphors reflect not the influence of technology per se, but the fact that the machine was becoming the model of social behavior.

A telling example of the new mechanical conception of the body is this 16th-century German engraving where the peasant is represented as nothing more than a means of production, with his body composed entirely of agricultural implements.

The inspirational force of the need for social control is evident even in the field of astronomy. A classic example is that of Edmond Halley (the secretary of the Royal Society), who, in concomitance with the appearance in 1695 of the comet later named after him, organized clubs all over England in order to demonstrate the predictability of natural phenomena, and to dispel the popular belief that comets announced social disorders. That the path of scientific rationalization intersected with the disciplining of the social body is even more evident in the social sciences. We can see, in fact, that their development was premised on the homogenization of social behavior, and the construction of a prototypical individual to whom all would be expected to conform. In Marx's terms, this is an "abstract individual," constructed in a uniform way, as a social average, and subject to a radical decharacterization, so that all of its faculties can be grasped only in their most standardized aspects. The construction of this new individual was the basis for the development of what William Petty would later call (using Hobbes' terminology) Political Arithmetics — a new science that was to study every form of social behavior in terms of Numbers, Weights, and Measures. Petty's project was realized with the development of statistics and demography (Wilson 1966; Cullen 1975) which perform on the social body the same operations that anatomy performs on the individual body, as they dissect the population and study its movements — from natality to mortality rates, from generational to occupational structures — in their most massified and regular aspects. Also from the point of view of the abstraction process that the individual underwent in the transition to capitalism, we can see that the development of the "human machine" was the main technological leap, the main step in the development of the productive forces that took place in the period of primitive accumulation. We can see, in other words, that the human body and not the steam engine, and not even the clock, was the first machine developed by capitalism.

J. Case. Compendium Anatomicum (1696). In contast to the "mechanical man" is this image of the "vegetable man" in which the blood vessels are seen as twigs growing out of the human body.

But if the body is a machine, one problem immediately emerges: how to make it work? Two different models of body-government derive from the theories of Mechanical Philosophy. On one side, we have the Cartesian model that, starting from the assumption of a purely mechanical body, postulates the possibility of developing in the individual mechanisms of self-discipline, self-management, and self-regulation allowing for voluntary work-relations and government based on consent. On the other side, there is the Hobbesian model that, denying the possibility of a body-free Reason, externalizes the functions of command, consigning them to the absolute authority of the state.

The development of a self-management theory, starting from the mechanization of the body, is the focus of the philosophy of Descartes, who (let us remember it) completed his intellectual formation not in the France of monarchical absolutism but in the bourgeois Holland so congenial to his spirit that he elected it as his abode. Descartes' doctrines have a double aim: to deny that human behavior can be influenced by external factors (such as the stars, or celestial intelligences), and to free the soul from any bodily conditioning, thus making it capable of exercising an unlimited sovereignty over the body.

Descartes believed that he could accomplish both tasks by demonstrating the mechanical nature of animal behavior. Nothing, he claimed in his Le Monde (1633), causes so many errors as the belief that animals have a soul like ours. Thus, in preparation for his Treatise of Man, he devoted many months to studying the anatomy of animal organs; every morning he went to the butcher to observe the quartering of the beasts.20 He even performed many vivisections, likely comforted by his belief that, being mere brutes "destitute of Reason," the animals he dissected could not feel any pain (Rosenfield 1968:8).21

To be able to demonstrate the brutality of animals was essential for Descartes, because he was convinced that here he could find the answer to his questions concerning the location, nature, and extent of the power controlling human conduct. He believed that in the dissected animal he would find proof that the body is only capable of mechanical, and involuntary actions; that, consequently, it is not constitutive of the person; and that the human essence, therefore, resides in purely immaterial faculties. The human body, too, is an automaton for Descartes, but what differentiates "man" from the beast and confers upon "him" mastery over the surrounding world is the presence of thought. Thus, the soul, which Descartes displaces from the cosmos and the sphere of corporeality, returns at the center of his philosophy endowed with infinite power under the guise of individual reason and will.

Placed in a soulless world and in a body-machine, the Cartesian man, like Prospero, could then break his magic wand, becoming not only responsible for his own actions, but seemingly the center of all powers. In being divorced from its body, the rational self certainly lost its solidarity with its corporeal reality and with nature. Its solitude, however, was to be that of a king: in the Cartesian model of the person, there is no egalitarian dualism between the thinking head and the body-machine, only a master/slave relation, since the primary task of the will is to dominate the body and the natural world. In the Cartesian model of the person, then, we see the same centralization of the functions of command that in the same period was occurring at the level of the state: as the task of the state was to govern the social body, so the mind became sovereign in the new personality.

Descartes concedes that the supremacy of the mind over the body is not easily achieved, as Reason must confront its inner contradictions. Thus, in The Passions of the Soul (1650), he introduces us to the prospect of a constant battle between the lower and higher faculties of the soul which he describes in almost military terms, appealing to our need to be brave, and to gain the proper arms to resist the attacks of our passions. We must be prepared to suffer temporary defeats, for our will might not always be capable of changing or arresting its passions. It can, however, neutralize them by diverting its attention to some other thing, or it can restrain the movements to which they dispose the body. It can, in other words, prevent the passions from becoming actions (Descartes 1973,1:354-55).

With the institution of a hierarchical relation between mind and body, Descartes developed the theoretical premises for the work-discipline required by the developing capitalist economy. For the mind's supremacy over the body implies that the will can (in principle) control the needs, reactions, reflexes of the body; it can impose a regular order on its vital functions, and force the body to work according to external specifications, independently of its desires.

Most importantly, the supremacy of the will allows for the interiorization of the mechanisms of power. Thus, the counterpart of the mechanization of the body is the development of Reason in its role as judge, inquisitor, manager, administrator. We find here the origins of bourgeois subjectivity as self-management, self-ownership, law, responsibility, with its corollaries of memory and identity. Here we also find the origin of that proliferation of "micro-powers" that Michel Foucault has described in his critique of the juridico-discursive model of Power (Foucault 1977). The Cartesian model shows, however, that Power can be decentered and diffused through the social body only to the extent that it is recentered in the person, which is thus reconstituted as a micro-state. In other words, in being diffused, Power does not lose its vectors that is, its content and its aims — but simply acquires the collaboration of the Self in their promotion.

Consider, in this context, the thesis proposed by Brian Easlea, according to which the main benefit that Cartesian dualism offered to the capitalist class was the Christian defense of the immortality of the soul, and the possibility of defeating the atheism implicit in Natural Magic, which was loaded with subversive implications (Easlea 1980: 132ff). Easlea argues, in support of this view, that the defense of religion was a central theme in Cartesianism, which, particularly in its English version, never forgot that "No Spirit, No God; No Bishop, No King" (ibid.: 202). Easlea's argument is attractive; yet its insistence on the "reactionary" elements in Descartes's thought makes it impossible for Easlea to answer a question that he himself raises. Why was the hold of Cartesianism in Europe so strong that, even after Newtonian physics dispelled the belief in a natural world void of occult powers, and even after the advent of religious tolerance, Cartesianism continued to shape the dominant worldview? I suggest that the popularity of Cartesianism among the middle and upper class was directly related to the program of self-mastery that Descartes' philosophy promoted. In its social implications, this program was as important to Descartes's elite contemporaries as the hegemonic relation between humans and nature that is legitimized by Cartesian dualism.

The development of self-management (i.e., self-government, self-development) becomes an essential requirement in a capitalist socio-economic system in which selfownership is assumed to be the fundamental social relation, and discipline no longer relies purely on external coercion. The social significance of Cartesian philosophy lies in part in the fact that it provides an intellectual justification for it. In this way, Descartes' theory of self-management defeats but also recuperates the active side of Natural Magic. For it replaces the unpredictable power of the magician (built on the subtle manipulation of astral influences and correspondences) with a power far more profitable — a power for which no soul has to be forfeited — generated only through the administration and domination of one's body and, by extension, the administration and domination of the bodies of other fellow beings. We cannot say, then, as Easlea does (repeating a criticism raised by Leibniz), that Cartesianism failed to translate its tenets into a set of practical regulations, that is, that it failed to demonstrate to the philosophers — and above all to the merchants and manufacturers — how they would benefit from it in their attempt to control the matter of the world (ibid.: 151).

If Cartesianism failed to give a technological translation of its precepts, it nonetheless provided precious information with regard to the development of "human technology." Its insights into the dynamics of self-control would lead to the construction of a new model of the person, wherein the individual would function at once as both master and slave. It is because it interpreted so well the requirements of the capitalist work-discipline that Descartes' doctrine, by the end of the 17th century, had spread throughout Europe and survived even the advent of vitalistic biology as well as the increasing obsolescence of the mechanistic paradigm.

The reasons for Descartes' triumph are clearest when we compare his account of the person with that of his English rival, Thomas Hobbes. Hobbes' biological monism rejects the postulate of an immaterial mind or soul that is the basis of Descartes' concept of the person, and with it the Cartesian assumption that the human will can free itself from corporeal and instinctual determinism.22 For Hobbes, human behavior is a conglomerate of reflex actions that follow precise natural laws, and compel the individual to incessantly strive for power and domination over others (Leviathan: 141ff). Thus the war of all against all (in a hypothetical state of nature), and the necessity for an absolute power guaranteeing, through fear and punishment, the survival of the individual in society.

For the laws of nature, as justice, equity, modesty, mercy, and, in sum, doing to others as we would be done to, of themselves, without the terror of some power to cause them to be observed, are contrary to our natural passions, that carry us to partiality, pride, revenge and the like (ibid.: 173).

As is well known, Hobbes' political doctrine caused a scandal among his contemporaries, who considered it dangerous and subversive, so much so that, although he strongly desired it, Hobbes was never admitted to the Royal Society (Bowie 1952:163).

Against Hobbes, it was the Cartesian model that prevailed, for it expressed the already active tendency to democratize the mechanisms of social discipline by attributing to the individual will that function of command which, in the Hobbesian model, is left solely in the hands of the state. As many critics of Hobbes maintained, the foundations of public discipline must be rooted in the hearts of men, for in the absence of an interior legislation men are inevitably led to revolution (quoted in Bowie 1951: 97—98). "In Hobbes," complained Henry Moore, "there is no freedom of will and consequently no remorse of conscience or reason, but only what pleases the one with the longest sword" (quoted in Easiest 1980; 159). More explicit was Alexander Ross, who observed that "it is the curb of conscience that restrains men from rebellion, there is no outward law or force more powerful... there is no judge so severe, no torturer so cruel as an accusing conscience" (quoted in Bowie 1952:167).

The contemporaneous critique of Hobbes' atheism and materialism was clearly not motivated purely by religious concerns. His view of the individual as a machine moved only by its appetites and aversions was rejected not because it eliminated the concept of the human creature made in the image of God, but because it eliminated the possibility of a form of social control not depending wholly on the iron rule of the state. Here, I argue, is the main difference between Hobbes' philosophy and Cartesianism. This, however, cannot be seen if we insist on stressing the feudal elements in Descartes' philosophy, and in particular its defense of the existence of God with all that this entailed, as a defense of the power of the state. If we do privilege the feudal Descartes we miss the fact that the elimination of the religious element in Hobbes (i.e. the belief in the existence of incorporeal substances) was actually a response to the democratization implicit in the Cartesian model of self-mastery which Hobbes undoubtedly distrusted. As the activism of the Puritan sects during the English Civil War had demonstrated, self-mastery could easily turn into a subversive proposition. For the Puritans' appeal to return the management of one's behavior to the individual conscience, and to make of one's conscience the ultimate judge of truth, had become radicalized in the hands of the sectaries into an anarchic refusal of established authority.23 The example of the Diggers and Ranters, and of the scores of mechanic preachers who, in the name of the "light of conscience," had opposed state legislation as well as private property, must have convinced Hobbes that the appeal to "Reason" was a dangerously double-edged weapon.24

The conflict between Cartesian "theism" and Hobbesian "materialism" was to be resolved in time in their reciprocal assimilation, in the sense that (as always in the history of capitalism) the decentralization of the mechanisms of command, through their location in the individual, was finally obtained only to the extent that a centralization occurred in the power of the state. To put this resolution in the terms in which the debate was posed in the course of the English Civil War; "neither the Diggers nor Absolutism," but a well-calculated mixture of both, whereby the democratization of command would rest on the shoulders of a state always ready, like the Newtonian God, to reimpose order on the souls who proceeded too far in the ways of self-determination. The crux of the matter was lucidly expressed by Joseph Glanvil, a Cartesian member of the Royal Society who, in a polemic against Hobbes, argued that the crucial issue was the control of the mind over the body. This, however, did not simply imply the control of the ruling class (the mind par excellence) over the body-proletariat, but, equally important, the development of the capacity for self-control within the person.

As Foucault has demonstrated, the mechanization of the body did not only involve the repression of desires, emotions, or forms of behavior that were to be eradicated. It also involved the development of new faculties in the individual that would appear as other with respect to the body itself, and become the agents of its transformation. The product of this alienation from the body; in other words, was the development of individual identity, conceived precisely as "otherness" from the body, and in perennial antagonism with it.

The emergence of this alter ego, and the determination of a historic conflict between mind and body, represent the birth of the individual in capitalist society. It would become a typical characteristic of the individual molded by the capitalist work-discipline to confront one's body as an alien reality to be assessed, developed and kept at bay, in order to obtain from it the desired results.

As we pointed out, among the "lower classes" the development of self-management as self-discipline remained, for a long time, an object of speculation. How little self-discipline was expected from the "common people" can be judged from the fact that, right into the 18th century, 160 crimes in England were punishable by death (Linebaugh 1992), and every year thousands of "common people" were transported to the colonies or condemned to the galleys. Moreover, when the populace appealed to reason, it was to voice anti-authoritarian demands, since self-mastery at the popular level meant the rejection of the established authority, rather than the interiorization of social rule.

Indeed, through the 17th century, self-management remained a bourgeois prerogative. As Easlea points out, when the philosophers spoke of "man" as a rational being they made exclusive reference to a small elite made of white, upper-class, adult males. "The great multitude of men," wrote Henry Power, an English follower of Descartes, "resembles rather Descartes' automata, as they lack any reasoning power, and only as a metaphor can be called men" (Easlea 1980:140).25 The "better sorts" agreed that the proletariat was of a different race. In their eyes, made suspicious by fear, the proletariat appeared as a "great beast," a "many-headed monster," wild, vociferous, given to any excess (Hill 1975: 181ff; Linebaugh and Rediker 2000). On an individual level as well, a ritual vocabulary identified the masses as purely instinctual beings. Thus, in the Elizabethan literature, the beggar is always "lusty," and "sturdy," "rude," "hot-headed," "disorderly" are the ever-recurrent terms in any discussion of the lower class.

In this process, not only did the body lose all naturalistic connotations, but a body-function began to emerge, in the sense that the body became a purely relational term, no longer signifying any specific reality, but identifying instead any impediment to the domination of Reason. This means that while the proletariat became a "body," the body became "the proletariat," and in particular the weak, irrational female (the "woman in us," as Hamlet was to say) or the "wild" African, being purely defined through its limiting function, that is through its "otherness" from Reason, and treated as an agent of internal subversion.

Yet, the struggle against this "great beast" was not solely directed against the "lower sort of people." It was also interiorized by the dominant classes in the battle they waged against their own "natural state." As we have seen, no less than Prospero, the bourgeoisie too had to recognize that "[t]his thing of darkness is mine," that is, that Caliban was part of itself (Brown 1988; Tyllard 1961:34—35). This awareness pervades the literary production of the 16th and 17th centuries. The terminology is revealing. Even those who did not follow Descartes saw the body as a beast that had to be kept incessantly under control.

Its instincts were compared to "subjects" to be "governed," the senses were seen as a prison for the reasoning soul.

O who shall, from this Dungeon, raise

A Soul inslav'd so many wayes?

asked Andrew Marvell, in his "Dialogue Between the Soul and the Body"

With bolts of Bones, that fetter'd stands

In Feet; and manacled in Hands.

Here blinded with an Eye; and there

Deaf with the drumming of an Ear.

A Soul hung up, as t'were, in

Chain Of Nerves, and Arteries, and Veins

(quoted by Hill 1964b: 345).

The conflict between appetites and reason was a key theme in Elizabethan literature (Tillyard 1961:75), while among the Puritans the idea began to take hold that the "Antichrist" is in every man. Meanwhile, debates on education and on the "nature of man" current among the "middle sort" centered around the body/mind conflict, posing the crucial question of whether human beings are voluntary or involuntary agents.

But the definition of a new relation with the body did not remain at a purely ideological level. Many practices began to appear in daily life to signal the deep transformations occurring in this domain: the use of cutlery, the development of shame with respect to nakedness, the advent of "manners" that attempted to regulate how one laughed, walked, sneezed, how one should behave at the table, and to what extent one could sing, joke, play (Elias 1978: 129ff). While the individual was increasingly dissociated from the body, the latter became an object of constant observation, as if it were an enemy. The body began to inspire fear and repugnance. "The body of man is full of filth," declared Jonathan Edwards, whose attitude is typical of the Puritan experience, where the subjugation of the body was a daily practice (Greven 1977:67). Particularly repugnant were those bodily functions that directly confronted "men" with their "animality." Witness the case of Cotton Mather who, in his Diary, confessed how humiliated he felt one day when, urinating against a wall, he saw a dog doing the same:

Thought I ‘what vile and mean Things are the Children of Men in this mortal State. How much do our natural Necessities abase us, and place us in some regard on the same level with the very Dogs'... Accordingly I resolved that it should be my ordinary Practice, whenever I step to answer the one or the other Necessity of Nature, to make it an Opportunity of shaping in my Mind some holy, noble, divine Thought (ibid.).

The great medical passion of the time, the analysis of excrements — from which manifold deductions were drawn on the psychological tendencies of the individual (vices, virtues) (Hunt 1970:143-46) — is also to be traced back to this conception of the body as a receptacle of filth and hidden dangers. Clearly, this obsession with human excrements reflected in part the disgust that the middle class was beginning to feel for the non-productive aspects of the body — a disgust inevitably accentuated in an urban environment where excrements posed a logistic problem, in addition to appearing as pure waste. But in this obsession we can also read the bourgeois need to regulate and cleanse the body-machine from any element that could interrupt its activity, and create "dead time" in the expenditure of labor. Excrements were so much analyzed and debased because they were the symbol of the "ill humors" that were believed to dwell in the body, to which every perverse tendency in human beings was attributed. For the Puritans they became the visible sign of the corruption of human nature, a sort of original sin that had to be combatted, subjugated, exorcised. Hence the use of purges, emetics, and enemas that were administered to children or the "possessed" to make them expel their devilries (Thorndike 1958:553ff).

In this obsessive attempt to conquer the body in its most intimate recesses, we see reflected the same passion with which, in these same years, the bourgeoisie tried to conquer — we could say "colonize"— that alien, dangerous, unproductive being that in its eyes was the proletariat. For the proletarian was the great Caliban of the time. The proletarian was that "material being by itself raw and undigested" that Petty recommended be consigned to the hands of the state, which, in its prudence, "must better it, manage it, and shape it to its advantage" (Fumiss 1957:17ff).

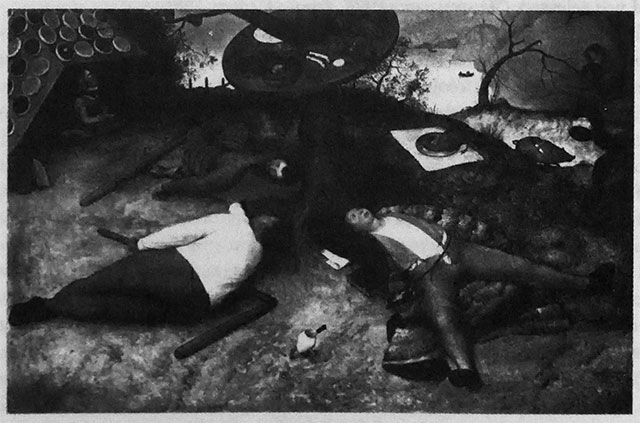

Like Caliban, the proletariat personified the "ill humors" that hid in the social body, beginning with the disgusting monsters of idleness and drunkenness. In the eyes of his masters, its life was pure inertia, but at the same time was uncontrolled passion and unbridled fantasy, ever ready to explode in riotous commotions. Above all, it was indiscipline, lack of productivity, incontinence, lust for immediate physical satisfaction; its utopia being not a life of labor, but the land of Cockaigne (Burke 1978; Graus 1987),26 where houses were made of sugar, rivers of milk, and where not only could one obtain what one wished without effort, but one was paid to eat and drink:

To sleep one hour

of deep sleep

without waking

one earns six francs;

and to drink well

one earns a pistol;

this country is jolly,

one earns ten francs a day

to make love (Burke: 190).

The idea of transforming this lazy being, who dreamt of life as a long Carnival, into an indefatigable worker, must have seemed a desperate enterprise. It meant literally to "turn the world upside down," but in a totally capitalist fashion, where inertia to command would be transformed into lack of desire and autonomous will, where vis erotica would become vis lavorativa, and where need would be experienced only as lack, abstinence, and eternal indigence.

Hence this battle against the body, which characterized the early phase of capitalist development, and which has continued, in different ways, to our day. Hence that mechanization of the body, which was the project of the new Natural Philosophy, and the focal point for the first experiments in the organization of the state. If we move from the witchhunt to the speculations of Mechanical Philosophy, and the Puritans' meticulous investigations of individual talents, we see that a single thread ties the seemingly divergent paths of social legislation, religious reform, and the scientific rationalization of the universe. This was the attempt to rationalize human nature, whose powers had to be rechannelled and subordinated to the development and formation of labor-power.

As we have seen, the body was increasingly politicized in this process; it was denaturalized and redefined as the "other," the outer limit of social discipline. Thus, the birth of the body in the 17th century also marked its end, as the concept of the body would cease to define a specific organic reality, and become instead a political signifier of class relations, and of the shifting, continuously redrawn boundaries which these relations produce in the map of human exploitation.

Endnotes

1. Prospero is a "new man." Didactically, his misfortunes are attributed by Shakespeare to his excessive interest in magic books, which in the end he renounces for a more active life in his native kingdom, where he will draw his power not from magic, but from the government of his subjects. But already in the island of his exile, his activities prefigure a new world order, where power is not gained through a magic wand but through the enslavement of many Calibans in far distant colonies. Prospero's exploitative management of Caliban prefigures the role of the future plantation master, who will spare no torture nor torment to force his subjects to work. ↩

2. "[E]very man is his own greatest enemy, and as it were, his own executioner,"Thomas Browne writes. Pascal, too, in the Pensee, declares that: "There is internal war in man between reason and the passions. If he had only reasons without passions....If he had only passions without reason....But having both, he cannot be without strife.... Thus he is always divided against, and opposed to himself (Pensee, 412:130). On the Passions/Reason conflict, and the "correspondences" between the human "microcosm" and the "body politic," in Elizabethan literature see Tillyard (1961:75-79; 94-99). ↩

3. The reformation of language — a key theme in 16th and 17th-century philosophy, from Bacon to Locke — was a major concern of Joseph Glanvil, who in his Vanity of Dogmatizing (1665), after proclaiming his adherence to the Cartesian world view, advocates a language fit to describe clear and distinct entities (Glanvil 1970: xxvi-xxx). As S. Medcalf sums it up in his introduction to Glanvils work, a language fit to describe such a world will bear broad similarities to mathematics, will have words of great generality and clarity; will present a picture of the universe according to its logical structure; will distinguish sharply between mind and matter, and between subjective and objective, and "will avoid metaphor as a way of knowing and describing, for metaphor depends on the assumption that the universe does not consist of wholly distinct entities and cannot therefore be fully described in positive distinct terms..." (ibid.: xxx). ↩

4. Marx does not distinguish between male and female workers in his discussion of the "liberation of labor-power." There is, however, a reason for maintaining the masculine in the description of this process. While "freed" from the commons, women were not channeled onto the path of the wage-labor market. ↩

5. "With labour I must earn / My bread; what harm? Idleness had been worse; / My labour will sustain me" is Adam's answer to Eve's fears at the prospect of leaving the blessed garden (Paradise Lost, verses 1054-56, p. 579). ↩

6. As Christopher Hill points out, until the 15th century, wage-labor could have appeared as a conquered freedom, because people still had access to the commons and had land of their own, thus they were not solely dependent on a wage. But by the 16th century, those who worked for a wage had been expropriated; moreover, the employers claimed that wages were only complementary, and kept them at their lowest level. Thus, working for a wage meant to fall to the bottom of the social ladder, and people struggled desperately to avoid this lot (Hill, 1975: 220-22). By the 17th century wage-labor was still considered a form of slavery, so much so that the Levelers excluded wage workers from the franchise, as they did not consider them independent enough to be able to freely choose their representatives (Macpherson 1962:107—59). ↩

7. When in 1622 Thomas Mun was asked by James I to investigate the causes of the economic crisis that had struck the country, he concluded his report by blaming the problems of the nation on the idleness of the English workers. He referred in particular to "the general leprosy of our piping, potting, feasting, factions and misspending of our time in idleness and pleasure" which, in his view, placed England at a disadvantage in its commercial competition with the industrious Dutch (Hill, 1975:125). ↩

8. (Wright 1960: 80-83; Thomas 1971; Van Ussel 1971: 25-92; Riley 1973: 19ff; Underdown 1985:7-72). ↩

9. The fear the lower classes (the "base," "meaner sorts," in the jargon of the time) inspired in the ruling class can be measured by this tale narrated in Social England Illustrated (1903). In 1580, Francis Hitchcock, in a pamphlet tided "New Year's Gift to England," forwarded the proposal to draft the poor of the country into the Navy, arguing: "the poorer sort of people are... apt to assist rebellion or to join with whomsoever dare to invade this noble island... then they are meet guides to bring soldiers or men of war to the rich mens wealth. For they can point with their finger ‘there it is', ‘yonder it is' and ‘He hath it', and so procure martyrdom with murder to many wealthy persons for their wealth...." Hitchcock's proposal, however, was defeated; it was objected that if the poor of England were drafted into the navy they would steal the ships or become pirates (Social England Illustrated 1903:85-86). ↩

10. Eli F. Heckscher writes that "In his most important theoretical work A Treatise of Taxes and Contributions (1662) [Sir William Petty] suggested the substitution of compulsory labour for all penalties, ‘which will increase labour and public wealth'." "Why [he inquired] should not insolvent Thieves be rather punished with slavery than death? So as being slaves they may be forced to as much labour, and as cheap fare, as nature will endure, and thereby become as two men added to the Commonwealth, and not as one taken away from it" (Heckscher 1962, II: 297). In France, Colbert exhorted the Court of Justice to condemn as many convicts as possible to the galleys in order to "maintain this corps which is necessary to the state" (ibid.: 298—99). ↩

11. The Treatise on Man (Traite de l'Homme), which was published twelve years after Descartes' death as L'Homme de Rent Descartes (1664), opens Descartes' "mature period." Here, applying Galileo's physics to an investigation of the attributes of the body, Descartes attempted to explain all physiological functions as matter in motion. "I desire you to consider" (Descartes wrote at the end of the Treatise) "...that all the functions that I have attributed to this machine... follow naturally... from the disposition of the organs — no more no less than do the movements of a clock or other automaton, from the arrangement of its counterweights and wheels" (Treatise: 113). ↩

12. It was a Puritan tenet that God has given "man" special gifts fitting him for a particular Calling; hence the need for a meticulous self-examination to resolve the Calling for which we have been designed (Morgan 1966:72-73; Weber 1958:47ff). ↩

13. As Giovanna Ferrari has shown, one of the main innovations introduced by the study of anatomy in 16th-century Europe was the "anatomy theater," where dissection was organized as a public ceremony, subject to regulations similar to those that governed theatrical performances: ↩

Both in Italy and abroad, public anatomy lessons had developed in modem times into ritualized ceremonies that were held in places specially set aside for them. Their similarity to theatrical performances is immediately apparent if one bears in mind certain of their features: the division of the lessons into different phases... the institution of a paid entrance ticket and the performance of music to entertain the audience, the rules introduced to regulate the behaviour of those attending and the care taken over the "production." W.S. Heckscher even argues that many general theater techniques were originally designed with the performance of public anatomy lessons in mind (Ferrari 1987:82—83).

14. According to Mario Galzigna, the epistemological revolution operated by anatomy in the 16th century is the birthplace of the mechanistic paradigm. It is the anatomical coupure that breaks the bond between microcosm and macrocosm, and posits the body both as a separate reality and as a place of production, in Vesalius' words: a factory (fabrica). ↩

15. Also in The Passions of the Soul (Article VI), Descartes minimizes "the difference that exists between a living body and a dead body": ↩

...we may judge that the body of a living man differs from that of a dead man just as does a watch or other automaton (i.e. a machine that moves of itself), when it is wound up and contains in itself the corporeal principle of those movements ... from the same watch or other machine when it is broken and when the principle of its movement ceases to act (Descartes 1973,Vol. I, ibid.).

16. Particularly important in this context was the attack on the "imagination" ("vis imaginativa") which in 16th and 17th-century Natural Magic was considered a powerful force by which the magician could affect the surrounding world and bring about "health or sickness, not only in its proper body, but also in other bodies" (Easlea 1980: 94ff). Hobbes devoted a chapter of the Leviathan to demonstrating that the imagination is only a "decaying sense," no different from memory, only gradually weakened by the removal of the objects of our perception (Part I, Chapter 2); a critique of imagination is also found in Sir Thomas Browne's Religio Medici (1642). ↩

17. Writes Hobbes: "No man therefore can conceive any thing, but he must conceive it in some place... not that anything is all in this place and all in another place at the same time; nor that two or more things can be in one and the same place at once" (Leviathan: 72). ↩

18. Among the supporters of the witch-hunt was Sir Thomas Browne, a doctor and reputedly an early defender of "scientific freedom," whose work in the eyes of his contemporaries "possessed a dangerous savour of skepticism" (Gosse 1905: 25). Thomas Browne contributed personally to the death of two women accused of being "witches" who, but for his intervention, would have been saved from the gallows, so absurd were the charges against them (Gosse 1905:147—49). For a detailed analysis of this trial see Gilbert Geis and Ivan Bunn (1997). ↩

19. In every country where anatomy flourished, in 16th-century Europe, statutes were passed by the authorities allowing the bodies of those executed to be used for anatomical studies. In England "the College of Physicians entered the anatomical field in 1565 when Elizabeth I granted them the right of claiming the bodies of dissected felons" (O'Malley 1964). On the collaboration between the authorities and anatomists in 16th and 17th-century Bologna, see Giovanna Ferrari (pp. 59, 60,64, 87-8), who points out that not only those executed but also the "meanest" of those who died at the hospital were set aside for the anatomists. In one case, a sentence to life was commuted into a death sentence to satisfy the demand of the scholars. ↩

20. According to Descartes' first biographer, Monsieur Adrien Baillet, in preparation for his Treatise of Man, in 1629, Descartes, while in Amsterdam, daily visited the slaughterhouses of the town, and performed dissections on various parts of animals: ↩

...he set about the execution of his design by studying anatomy, to which he devoted the whole of the winter that he spent in Amsterdam. To Father Mersenne he testified that his eagerness for knowledge of this subject had made him visit, almost daily, a butcher's, to witness the slaughter; and that he had caused to be brought thence to his dwelling whichever of the animals' organs he desired to dissect at greater leisure. He often did the same thing in other places where he stayed after that, finding nothing personally shameful, or unworthy his position, in a practice that was innocent in itself and that could produce quite useful results. Thus, he made fun of certain maleficent and envious person who... had tried to make him out a criminal and had accused him of "going through the villages to see the pigs killed" [H]e did not neglect to look at what Vesalius and the most experienced of other authors had written about anatomy. But he taught himself in a much surer way by personally dissecting animals of different species (Descartes 1972: xiii—xiv).

In a letter to Mersenne of 1633, he writes: "J'anatomize maintenant les tetes de divers animaux pour expliquer en quoi consistent l'imagination, la memoire..." (Cousin Vol.IV: 255). Also in a letter of January 20 he refers in detail to experiments of vivisection: "Apres avoir ouverte la poitrine d'un lapin vivant... en sorte que le tron et ie coeur de 1'aorte se voyent facilement.... Poursuivant la dissection de cet animal vivant je lui coupe cette partie du coeur qu'on nomme sa pointe" (ibid. Vol VII: 350). Finally, in June 1640, in response to Mersenne, who had asked him why animals feel pain if they have no soul, Descartes reassured him that they do not; for pain exists only with understanding, which is absent in brutes (Rosenfield 1968:8).

This argument effectively desensitized many of Descartes' scientifically minded contemporaries to the pain inflicted on animals by vivisection. This is how Nicholas Fontaine described the atmosphere created at Port Royal by the belief in animal automatism: "There was hardly a solitaire, who didn't talk of automata.... They administered beatings to dogs with perfect indifference and made fun of those who pitied the creatures as if they had felt pain. They said that animals were clocks; that the cries they emitted when struck were only the noise of a little spring which had been touched, but that the whole body was without feeling. They nailed poor animals on boards by their four paws to vivisect them and see the circulation of the blood which was a great subject of conversation" (Rosenfield 1968: 54).