- Return to book

- Review this book

- About the author

- Publishing Info

- 1. Contents

- 2. Acknowledgments

- 3. Introduction by Joy James

- 4. Author's Preface, 2007

- 5. Foreword: Police and Power in America

- 6. One: Police Brutality in Theory and Practice

- 7. Two: The Origins of American Policing

- 8. Three: The Genesis of a Policed Society

- 9. Four: Cops and Klan, Hand in Hand

- 10. Five: The Natural Enemy of the Working Class

- 11. Six: Police Autonomy and Blue Power

- 12. Seven: Secret Police, Red Squads, and the Strategy of Permanent Repression

- 13. Eight: Riot Police or Police Riots?

- 14. Nine: Our Friendly Neighborhood Police State

- 15. Afterword: Making Police Obsolete

- 16. Notes

- 17. Selected Bibliography

- 18. Index

- 19. About the Author

8

Riot Police or Police Riots?

Despite the efforts of the intelligence agencies, opposition movements continue to arise, occasionally developing to the point of unrest. Naturally, when uprisings occur, the authorities must put them down. Governments necessarily have a stake in controlling political protest, especially when it becomes forceful enough to disrupt the usual course of things - that is, when it becomes an effective threat to the status quo. No one with an interest in retaining power can allow things to go so far as to actually jeopardize their ability to rule. But this presents a problem for the rulers of an alleged democracy, with its promises of civil rights, free speech, popular assembly, and the pretense that the people are actually in the driver's seat. Open repression may exacerbate a crisis and undercut the state's claim to legitimacy, while acquiescence may make the government seem weak and will surely carry with it unfavorable policy implications. There can be no question of whether to control political protest, but there is a clear question as to how this may best be accomplished [1].

Seattle, 1999: Dance Party, Street Fight, No-Protest Zone

The 1999 Seattle demonstrations against the World Trade Organization (WTO) precipitated a sharp controversy in the theory of crowd control, calling into question police strategies of the previous twenty-five years.

On the morning of November 30, 1999, tens of thousands of people filled downtown Seattle in protest against the World Trade Organization. Protesters surrounded the venue for the WTO's ministerial conference, blocking the delegates' access to the meeting and shutting down a large portion of the city. The protests were overwhelmingly peaceful; many took the form of dance parties in the street. On the demonstrators' side, the much-decried "violence" and "rioting" amounted to only a few broken windows and some tear gas thrown back in the direction of the police.

For most of that day, the police were helpless to restore order. They stood in small groups, blocking random streets, accomplishing nothing. Occasionally tear gas was used, and the police would advance a block, but that was all. For one day, the streets belonged to jubilant crowds. Shops were not open, cars could not pass, the WTO meeting was stalled at the outset. By nightfall, a curfew was in place and the National Guard was on patrol. It was announced that no more demonstrations would be allowed in the area of the conference. Police chased a crowd from downtown to the nearby Capitol Hill neighborhood, attacking every one the street along the way. The residents of Capitol Hill fought back, and a pitched battle ensued. The fighting continued late into the night.

On December 1, the streets belonged to the cops. Early that morning, the police arrested more than 600 people just outside the "No-Protest Zone." Police were shown on national television indiscriminately firing tear gas, rubber bullets, and other "less-lethal" munitions. Beatings were common - not only protesters, but bystanders and reporters were attacked. Still the demonstrations continued. On December 2, several hundred people surrounded the jail, demanding their comrades be released; a compromise was reached when the authorities allowed lawyers in to see the prisoners - the first legal access since the arrests began.

In the end, the protesters won. The WTO meeting started late and ended in failure; no new trade agreements were reached. Most of those arrested were released, with charges dropped. And Norm Stamper, Seattle Chief of Police, resigned in disgrace. People-workers, students, environmentalists, human rights activists-stood together against the WTO, the city government, the police, the National Guard, and the corporate powers they all represent. And the people won. Before the smoke had even cleared, authorities around the country were asking what had gone wrong and, more importantly, how they could prevent it from happening again [2].

Assessing the Police Response: "What Not to Do"

Everyone agrees that the police action at the WTO was an unmitigated disaster. A city council committee charged with reviewing the events noted, "this city became the laboratory for how American cities will address mass protests. In many ways, it became a vivid demonstration of what not to do [3]."

From a civil rights perspective, the 1999 WTO ministerial was marked by a virtual prohibition on free speech, a plague of arbitrary arrests, and wide spread police brutality. The ACLU described the situation this way:

Realizing it had lost control of the scene, the City then over-reacted. It violated free speech rights in a large part of downtown. Under the direction of the Seattle Police Department, police from Seattle and nearby jurisdictions used chemical weapons on peaceful crowds and people walking by. Losing discipline, police officers committed individual acts of brutality. Protesters were improperly arrested and mistreated in custody [4].

The city council's description of the events bears the standard characteristics of a police riot:

Our inquiry found troubling examples of seemingly gratuitous assaults on citizens, including use of less-lethal weapons like tear gas, pepper gas, rubber bullets, and "beanbag guns," by officers who seemed motivated more by anger or fear than professional law enforcement [5].

And police commanders admit that they lost control, not only of the streets, but of their troops as well:

An essential element for the successful execution of any plan is the ability to control operations once officers are deployed. Unfortunately, in several respects the command and control arrangements for WTO broke down early in the operation [6].

Nevertheless, from the law-and-order side, the protests represented a vast sea of lawlessness, complete with attacks against police and property. The Seattle Police Department After Action Report describes the protests from the police perspective:

Numerous acts of property damage, looting, and assaults on police were committed. Officers were pelted with sticks, bottles, traffic cones, empty chemical irritant canisters, and other debris. Some protesters used their own chemical irritants against police, and a large fire was set in the intersection at 4th and Pike [7].

What's remarkable is not so much the dispute between the police and civil rights advocates (not to mention the protesters), but the level of conflict between the city council and the police. Some of this was surely opportunistic posturing, a typical political game, with politicians scrambling to cover their asses, point accusing fingers, and associate themselves with the winners. But the dispute also represents a sharp split between the perspective of the city council (as presented in its Accountability Committee Report) and that of the police (argued mostly by proxy, in a report prepared by an independent consulting firm - R. M. McCarthy and Associates). Not only are their analyses in conflict - in places, even the facts they cite are at odds - but their suggested remedies are in direct opposition.

Funded by the mayor's office, the McCarthy and Associates report was written primarily by three retired law enforcement officers from New York and Los Angeles. They describe every step of the SPD's WTO operation and urge a more forceful response when dealing with future civil disobedience. They recommend establishing the siege-like atmosphere of December 1 well before any demonstrations begin, arguing that

had a restrictive safety zone been established, protest areas designated outside of the zone, and additional personnel from other agencies been planned for and deployed in a pre-emptive manner on November 26, the results would likely have been different [8].

The report also suggests that the police response didn't go far enough in the suppression of civil rights. "The review team believes the decision to allow any previously scheduled marches or demonstrations to proceed after violence had erupted was unwise [9]." Furthermore, it recommends amending police policy by removing instructions that crowds be moved or dispersed "peacefully," and adding explicit orders to make as many arrests as possible [10].

Luckily, elected officials are likely to balk at such draconian measures. Describing the McCarthy report as a "crude and unsatisfying" document, the City Councils Review Committee reached almost entirely opposing conclusions [11]. Rather than pressing for a more forceful response, the city council's committee suggested that in many cases the police would have done better to have done nothing at all. "Members of the public, including demonstrators, were victims of ill-conceived and sometimes pointless police actions to 'clear the streets [12].'" Aside from its brutality, such an approach is often self-defeating. For example, "The unintended consequence of police actions on Capitol Hill was to bring sleepy residents out of their homes and mobilize them as 'resistors [13].'"

Despite the objections to the McCarthy report, its recommended tactics are by now familiar in the setting of any large anti-globalization event. We've seen this pattern repeated time and again in Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, and Los Angeles (as well as in Prague , Quebec City, Gothenburg, and Genoa) [14] - and, with variations, in more recent anti-war protests [15].

Early Strategies

There is more at stake in this debate than the blame for the WRO debacle. Each of these reports represents one side in an ongoing dispute over the principles of crowd control. Spanning slightly more than 100 years, this controversy has been shaped by a series of similar crises - instances in which the police orthodoxy proved disastrous.

Prior to the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, civil disturbances were essentially handled like any other military engagement, with the possible exception that crowds would be ordered to disperse before the police or militia charged with clubs or opened fire. During the Draft Riots of 1863, for example, New York Police Commissioner Thomas Acton ordered those under his command to "Take no prisoners." George Walling, the commander of the twelfth precinct was even more specific in his instructions: "Kill every man who has a club [16]." I will term this the strategy of "Maximum Force."

Such an approach may have had a certain efficacy against localized revolts, unplanned riots, or drunken mobs, but it met with greater difficulty in 1877 when more than 100,000 railroad workers, enraged by cuts to their already meager wages, went on strike and prevented the companies from moving their freight [17]. The turmoil was too vast for local police to control, and the militia proved unreliable.

"In Pittsburgh, the city where strike-related violence climaxed, militia displayed opposite extremes of indiscipline: fraternization and panic [18]." The commander of the Pittsburgh militia later testified:

Meeting on the field of battle you go there to kill ... but here you had men with fathers and mothers and brothers and relatives mingled in the crowd of rioters. The sympathy was with the strikers. We all felt that these men were not receiving enough wages [19].

The Philadelphia militia, which was also sent to Pittsburgh, displayed no such sympathy. The New York Times reported that they "fired indiscriminately into the crowd, among whom were many women and children [20]." Rather than fleeing, the crowd was enraged; the militia was forced to retreat. Likewise, in Reading, when troops killed eleven strikers, the general population only grew more furious. Strike supporters looted freight, tore up tracks, and armed themselves with rifles from the militia's own armory. When reinforcements arrived, they sided with the crowds and threatened their colleagues, "If you fire at the mob, we'll fire at you [21]."

These same problems arose in every city facing strikes. In Newark, Ohio, and Hornellsville, New York, militia men openly fraternized with strikers, much to the dismay of their commanders. In Martinsburg, West Virginia, the commander of the Beverly light Guards telegraphed the governor, worried by his troops' sympathy with the strikers. In Harrisburg, Morristown, and Altoona, Pennsylvania, the militias surrendered. Half of the soldiers in the Maryland Sixth Regiment broke into an undisciplined retreat during a Baltimore street fight. And in Lebanon, Pennsylvania, a company of militia mutinied [22].

In the end, a combination of attrition, fatigue, and military force won out over the striking workers [23]. But still, the authorities were very disappointed. They immediately set about building the militias into well-disciplined machines, capable of quelling riots or, more to the point, breaking up strikes. During this period, the state militias were reconstituted into the modern National Guard [25]. Military training was imposed and matters of discipline rigidly enforced, including inspections by regular Army officers. In addition, more emphasis was placed on recruitment, and armories were built throughout the North [26].

These changes in the organization, training, discipline, and culture of the Guard were accompanied by new articulations of crowd control strategies. A number of manuals suddenly appeared spelling out the strategy for stifling unrest. These books were generally unconcerned with the social causes of disorder, content to blame them on agitators of various sorts. Most continued to advocate the principle of Maximum Force: they predicted increased militancy among workers, and offered increased state violence as the remedy [27]. E. L. Molineux, the commander of the New York National Guard, wrote: "In its incipient stage a riot can be readily quelled ... if met bodily and resisted at once with energy and determination. Danger lurks in delay [28]."

A milder version of the doctrine did emerge, and gained popularity among local commanders. According to this "Show of Force" (my term) theory:

Strikes and riots were outbursts that could be controlled - perhaps even prevented - by shows of authority which even rowdy workers were presumed to respect, or by shows of force which workers would fear. From these premises it followed that the function of the militia on riot duty was as much demonstrative, even theatrical, as it was coercive. The goal was to disperse rioters, not - as General Vodges would have it - to corner them and wipe them out [29].

And if this could be accomplished without firing a shot, so much the better. One manual stated, "[A] strong display of a well-disciplined and skillfully handled force will in most instances be sufficient in itself to suppress a riot [30]."

This presumption was later shown to be false: a large police presence is not so much preventive as it is provocative. Such errors were at least partly a product of the theory's underlying premise that rioters are psychologically deranged rather than politically or economically motivated. In any case, the practical consequence of the Show of Force theory was a new demand for dress uniforms, public drilling, and parades [31]. It was not shown to reduce the likelihood of class conflict or to prevent strikes.

In the 1880s, a wave of immigration made the authorities less reluctant to use force against striking workers [32]. And after the Haymarket incident of 1886, the Show of Force approach was almost entirely abandoned in favor of more direct responses: "[T]acticians [came] to favor the use of force over shows of force [33]." Tellingly, racist comparisons between workers and Native Americans became more common. In 1892 the Army and Navy Register opined, "The red savage is pretty well subdued ... but there are white savages growing more numerous and dangerous as our great cities become greater [34]." This analogy was not merely rhetorical; many of the same units were used against strikers as against indigenous peoples.

The Maximum Force approach did have its disadvantages. "Fire tactics appropriate for conventional warfare ... jeopardized innocent lives, invited public condemnation, and ... simply did not work in the urban terrain where most riots took place [35]." As the National Guard's reputation for brutality grew, so did sympathy for those who opposed them - especially striking workers. At the same time, Maximum Force was out of step with the authorities' overall strategy in handling strikes, as the government and businesses came to rely more and more on the pacifying effects of concessions [36]. Nevertheless, and despite atrocities like the Ludlow Massacre [37], Maximum Force remained the dominant approach well into the twentieth century.

Rationalizing Force

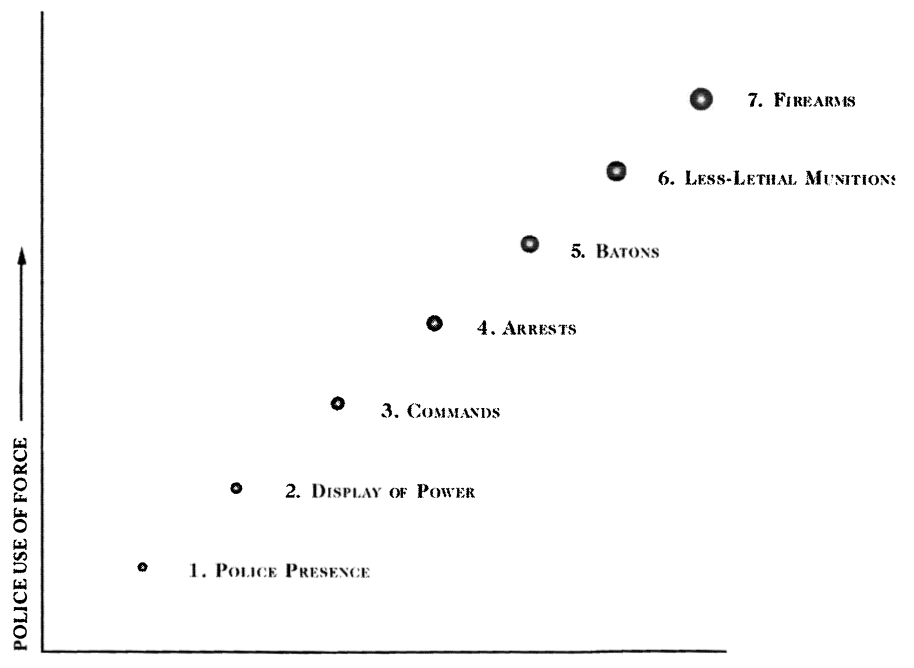

It was not until World War I and its accompanying Red Scare that the Maximum Force doctrine was revised. State violence was then rationalized - broken into discrete, ordered stages. This change represented one component in an early effort to take some of the conflict out of class conflict "In short, repealing bellicose post-Haymarket formulas for riot control was part of a multifaceted drive to wreck the Left, strip the working class of radical leaders, and put progressive managers in their place [38]."

Of the new crowd-control strategists, the most influential was Henry A Bellows, an officer in the Minnesota Home Guard and the author of A Manual for Local Defense (1919) and A Treatise on Riot Duty for the National Guard (1920). In these works, he drew a distinction between crowds and mobs, and argued that the key was to keep a crowd from becoming a mob. Ideally this could be accomplished by preventing crowds from forming in the first place or, failing that, by breaking up any crowd that did form and doing so before it had the chance to transform into a mob. The crowd should be dispersed with as little actual violence as possible, but without hesitating to use whatever force was necessary [39]. Bellows wrote, "Practically every riot can be prevented without bloodshed ... if sufficient force can be brought to bear on it in time [40]."

Army Major Richard Stockton and New Jersey National Guard Captain Saskett Dickson expressed a similar view in their Troops on Riot Duty: A Manual for the Use of the Armed Forces of the United States. They wrote:

Troops on riot duty should keep in mind the fact that they are called upon to put down disorder, absolutely and promptly, with as little force as possible, but it should be remembered, also, that in the majority of cases the way to accomplish these ends is to use at once every particle of force necessary to stop all disorder [41].

The new theorists sought a doctrine by which force would be prescribed in proportion to the difficulty of dispersing the crowd. They thus advocated using tactics suited to the particular situation.

In terms of tactics, giving priority to prevention demanded what later military thinkers would call doctrines of "sequence of force" or "flexible response." Simply put, the idea was to adapt levels of forces [sic] to levels of perceived menace, escalating to fire-power only as a last resort.... All of the writers of 1918-1920 endorsed the initial use of verbal warnings, bayonets, rifle butts, or hoses, as alternatives to firepower [42].

By 1940, the Show of Force doctrine had been reinserted as the first step of this progression [43].

In this way, the doctrine of Maximum Force was transformed into that of Escalated Force, which remained the standard approach to crowd control until the 1970s.

As its name indicates , the escalated force style of protest policing was characterized by the use of force as a standard way of dealing with demonstrations. Police confronted demonstrators with a dramatic show of force and followed with a progressively escalated use of force if demonstrators failed to abide by police instructions to limit or stop their activities [44].

Such force took different forms. Sometimes, arrests immediately followed even minor violations of the law, or were used to target and remove "agitators," whether or not a law had been broken. Other times, police used force instead of making arrests, either to break up the crowd or to punish those who disobeyed them [45].

The Applications and Implications of Escalated Force

According to the Escalated Force theory, violence is only used in proportion to the threat posed by the crowd. The reality is often quite different. The police response to protests is determined by something more than the behavior of protesters. In fact, the actions of the crowd may not even be the most important factor. Others may include police preparedness and discipline, the presence of counter-demonstrators, the number of participants, media coverage, and the political calculus surrounding the event - that is, what people with power, and the police leaders in particular, stand to gain or lose by attacking the event or letting it alone. These factors can be classed into six groups:

- the organizational features of the police;

- the configuration of political power;

- public opinion:

- the occupational culture of the police;

- the interaction between police and protesters; and,

- police knowledge [46].

Even when the police do respond in proportion to the threat, their victims often include peaceable demonstrators and innocent bystanders, along with the hooligans. Widespread violence is by its nature imprecise. And questions of "guilt" or "innocence," like those pertaining to constitutional rights are of secondary concern, if indeed they are considered relevant at all. Dispersal operations are not designed to uphold the law or to protect public safety; often the police action itself will represent the most serious violation of the law and constitute the greatest threat to the safety of the community. Instead of the law or public safety, the police are concerned with establishing control, maintaining power [47].

Well-known demonstrations in which police used the escalated force approach include those in the Birmingham civil rights campaign (May 1963), the 1968 Chicago Democratic National Convention, and the confrontation between student protesters and National Guard soldiers at Kent State University (May 1970). During each of these demonstrations, police or soldiers used force in an attempt to disperse demonstrators, even demonstrators who were peacefully attempting to exercise their First Amendment rights - as the vast majority of them were [48].

These events, while large in scope and attracting a great deal of media attention, were not uncharacteristic of Escalated Force operations. In many ways, they were sadly typical. While Kent State - where the victims were White - has come to symbolize the murder of student protesters, it was not the first or last time that students were shot in the name of keeping order. In May 1967 - three years before Kent State - a Black student was killed at Jackson State College in Mississippi. In February 1968, three students were killed at South Carolina State College. One was killed in Berkeley in May 1969, and another at North Carolina Agricultural and Mechanical College that same month. One was killed in Santa Barbara in February 1970. In March 1970, twelve were shot, but no one killed, at State University of New York, Buffalo. Most famously, in May 1970, four were murdered at Kent State. That same month, twenty were shot just down the road at Ohio State (all survived), and fourteen were shot (again) at Jackson State, two of whom died. In July 1970, one was killed at the University of Kansas, Lawrence, and another at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. Two years later, in November 1972, two more students were killed at the University of New Orleans [49].

Predictably, urban Black people received even worse treatment. In the Detroit uprising of 1967, forty-three people were killed, thirty-six of whom were Black. Twenty-nine of these deaths were definitely attributable to police, National Guard troops, or the Army. The remaining thirteen died from any of a variety of causes: some were shot by store owners, some died in fires, two were electrocuted by fallen power lines. No deaths were directly attributable to the violence of the crowds. Despite the rhetoric surrounding them, Black uprisings in the sixties "were marked by a relative absence of violence committed by rioters against people. Careful examination of the casualty lists shows that police and military inflicted the vast majority of fatalities and injuries on blacks in the riot area [50]."

A Glimpse at 1968

These facts speak to the level of police violence, but they say very little about its prevalence in crowd control situations. For that, we should consider a sample of police actions during a specific time frame - for example, during the year 1968, a banner year remembered for producing rebellions around the world. While in this respect 1968 is exceptional, it may also (for the same reasons) be seen to typify the official response to unrest. It certainly provided numerous, widely varied examples for comparison.

In January 1968, San Francisco police broke ranks and charged into the crowd at an anti-war demonstration, beating protesters. San Francisco also saw numerous rampages by the police department's Tactical Squad throughout the year, especially in the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood. During one such attack, a Black plainclothes officer was beaten by his White colleagues. During another, off-duty Tactical Squad officers moved through the Mission district, clearing sidewalks and assaulting pedestrians. Two officers went to trial for that stunt [51].

Three Black people were killed and almost fifty others injured when police and National Guard troops opened fire at a February demonstration against a White-only bowling alley in Orangeburg, South Carolina. Most of the wounded were shot in the back [52].

In March, New York City police attacked a Yippie demonstration at Grand Central Station. Offering no opportunity for the crowd to disperse, they indiscriminately beat members of the crowd that had gathered. The same tactic was repeated at another Yippie march in April, this time in Washington Square [53]. Later that same month, Students for a Democratic Society held a demonstration at Rockefeller Center. Jeff Jones, an SDS organizer, described the event as "very militant, it turned into a street fight. I think there were eight felony and fourteen misdemeanour [sic] arrests. There were beatings on both sides [54]." A week later, on April 29, 1968, New York City police used clubs to clear some of the same students from occupied buildings at Columbia University. Police emptied the occupied buildings and then moved through the campus, beating any students they could find, whether or not they had been involved in the occupation [55]. One hundred thirty-two students and four faculty were injured [56]. Also in New York, that fall, 150 off-duty cops filled a Brooklyn courthouse and beat several Black Panthers who were there to observe a trial [57].

A week before he was assassinated, Martin Luther King, Jr., led 15,000 people on a march through Memphis, expressing solidarity with the city's striking garbage collectors. The police and National Guard used clubs and tear gas to break up the march, killing one person in the process [58]. In April, following King's murder, 202 riots occurred in 175 cities across the country, with 3,500 people injured and forty-three killed, mostly at the hands of police [59]. Also in April, a peace march of 8,000 moved slowly through downtown Chicago. Having been refused a parade permit marchers stayed on sidewalks and obeyed the traffic signals. Nevertheless, in an incident foreshadowing the Democratic National Convention later that year, a line of police pushed the crowd into the streets; almost at once, another line of cops pushed them back to the sidewalks. The situation quickly degenerated. Ignoring the orders of their superiors, police broke ranks, chasing and beating members of the crowd. A panel convened to study the incident lay the blame with Mayor Richard Daley and other city officials, who set the tone for the action by denying the required permits [60].

In June, cops attacked a crowd of Berkeley students listening to speeches about the Paris uprising, setting off several days of fighting [6]. In July, police responded forcefully to racial unrest in Paterson, New Jersey. A grand jury later condemned the police for engaging in "terrorism" and "goon squad" tactics. The jury reported that teams of cops intentionally vandalized Black-owned businesses and severely beat individual Black and Puerto Rican people as an example to others [62]. In August, Los Angeles exploded after police attacked a crowd at the Watts Festival. Three people were killed and thirty-five injured [63].

That winter, when students at San Francisco State College went on strike to demand a Black Studies program, college president S. I. Hayakawa declared a state of emergency, ordered classes to resume, and called in police to make sure that they did [64]. (Hayakawa is perhaps best remembered for his assertion, "There are no innocent bystanders [65].") Skirmishes followed throughout December, during which individual officers broke from their units and charged into crowds of students. News photos showed police holding protesters while other cops maced them [66]. The strike was finally defeated in January when police started making mass arrests, resulting in several felony convictions [67].

This chronology is undoubtedly incomplete, but it makes the point police violence against crowds, sometimes perfectly innocuous gatherings, was utterly common [68]. It was as frequent as it was extreme. Nevertheless, one event stands out as the paradigmatic police riot - the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

Anatomy of a Police Riot

Televised footage of the 1968 Democratic National Convention shocked the nation [69]. Mobs of police were filmed beating protesters, bystanders, and reporters viciously and indiscriminately. Over 100 people were hospitalized as the result of police violence [70]. Senator Abraham Ribicoff spoke on the floor of the convention against the "Gestapo tactics in the streets of Chicago [71]." George McGovern described the scene as a "blood bath," also making comparison to "Nazi Germany [72]."

Norman Mailer commented:

What staggered the delegates who witnessed the attack - more accurate to call it the massacre, since it was sudden, unprovoked, and total - on Michigan Avenue, was that it opened the specter of what it might mean for the police to take over society. They might comport themselves in such a case not as a force of law and order, not even as a force of repression upon civil disorder, but as a true criminal force; chaotic, improvisational, undisciplined, and finally - sufficiently aroused - uncontrollable [73].

Mailer's characterization of police behavior closely matches that produced by more systematic studies. Daniel Walker, in his authoritative report on the DNC, notes, "Fundamental police training was ignored; and officers, when on the scene, were often unable to control their men [74]." Walker's report offers this example:

A high-ranking Chicago police commander admits that on [at least one] occasion the police "got out of control." This same commander appears in one of the most vivid scenes of the entire week, trying desperately to keep individual policemen from beating demonstrators as he screams, "For Christ's sake , stop it [75]!"

Such a breakdown in command, when paired with the widespread and excessive use of force, is perhaps the defining mark of the classic police riot [76]. In his book, Police Riots: Collective Violence and Law Enforcement, sociologist Rodney Stark offers a six-step outline as to how these riots unfold:

"Convergence" - There must be substantial numbers on both sides.

"Confrontation" - Either police actions attract hostile crowds, or police deem some gathering illegal and move in to break it up.

"Dispersal"-Police attempt to break up the crowd.

"The Utilization of Force" - Police use force against the crowd.

"The Limited Riot" - Excessive or punitive force ends once the crowd is dispersed. The limited police riot is often signified by the disintegration of police formations into small autonomous groups, charging into crowds, chasing fleeing individuals, and beating people up.

"The Extended Police Riot" - Attacks continue even after the crowd has dispersed. Extended riots are most common in densely populated areas, like college campuses or urban ghettos. Then, police attacks often attract new crowds, thus renewing confrontations [77].

There are a number of factors that, in the right circumstances, give police actions this trajectory. Among them are specific crowd control tactics, operational deficiencies, the machismo inherent to cop culture, and a paranoid ideology that leads police to overestimate the threat crowds pose [79].

On the tactical level, Stark notes:

The incapacities and misconceptions of the police contribute to the occurrence of police riots in a number of ways. First, simply massing the police together, given their lack of discipline and tactical competence, provides an opportunity for them to attack crowds. Second, massive displays of police power provoke demonstrators and tend to produce confrontations and deeper conflicts. Third, police tactics mislead policemen about what is expected of them and increases [sic] their anxiety and hostility. The obsession with officer safety leads to overpreparedness, overreaction, and a disregard for the general safety [80].

Add to this an habitual reliance on violence, and the production of a riot seems quite predictable [81].

These difficulties are exacerbated by organizational weaknesses common to police departments, namely the lack of internal discipline. The tactics of riot control are generally derived from the military, but the police proved to be a very different type of organization than the Army. "To put it bluntly: the American police cannot perform at the minimum levels of teamwork, impersonality, and discipline which these military tactics take for granted [82]." For example, in the Detroit riot of 1967, the police and National Guard were responsible for establishing order on one side of town; U.S. Army paratroopers were assigned to the other side. Within a few hours, the Army had restored order in their area, having fired 201 rounds of ammunition and having killed one person. The police and Guard, in contrast, fired thousands of rounds and killed twenty-eight people, while the disorder continued.

These dramatic and critical differences seem to have stemmed from discipline. The paratroopers had it, the police and guardsmen did not. The Army ordered the lights back on and troopers to show themselves as conspicuously as possible; the police and the guardsmen continued shooting out all lights and crouched fearfully in the darkness. The troopers were ordered to hold their fire, and did so. The police and guardsmen shot wildly and often at one another. The troopers were ordered to unload their weapons, and did so. The guardsmen were so ordered, but did not comply [83].

The Guard, whose training approximates that of the Army, may have lost discipline in part because of how they were deployed. The police effectively disorganized the National Guard by converting it into a police force. One National Guard commander complained:

They sliced us like baloney. The police wanted bodies. They grabed [sic] Guardsmen as soon as they reached the armories, before their units were made up, and sent them out-two on a firetruck, this one in a police car, that one to guard some installation.... The Guard simply became lost boys in the big town carrying guns [84].

In the caSe of the 1968 Democratic Convention, other factors also came into play, in particular the attitudes of civil authorities. Walker mentions, "Chicago police [had been led] to expect that violence against demonstrators, as against rioters, would be condoned by city officials [85]." In fact, this expectation was validated; Mayor Daley continued to defend his officers long after his excuses could be considered in any way credible [86]. One further fact complicates the picture: much of the convention-week violence was planned. Some reporters received warnings from cops with whom they were friendly; they were told the police intended to target members of the media [87]. With these facts in mind, the police riot seems to take on a different air. The cops did not simply panic; they knew what they meant to do. While internal discipline broke down, the police action as a whole filled its intended role. Indeed, the cops had been encouraged, and then protected, by the mayor. Certain commanders may have been appalled by what they saw - or may simply have been afflicted by the managerial need to assert their authority in a crisis - but this did nothing to affect the behavior of the institution as a whole.

Finally, it should be noted that the Escalated Force strategy itself contributes to the likelihood of a police riot. The police riot, by Stark's analysis, moves along exactly the same lines as the Escalated Force model. (In fact, Stark refers to his six-stage articulation as an "Escalation Model [88].") The crowd control operation ends and the riot begins at the point where discipline breaks down. The implementation of the Escalated Force strategy tends to race toward this point. In practice, police commanders "tend to maximize rather than minimize the use of force in order to maximize officer safety and to maximize dispersal" even though "command control and tactical integrity tend to collapse in contact with crowds and as greater force is applied [89]." In other words, as the amount of force is increased, the likelihood that discipline will be lost and that excessive force will be used also increases. This lapse, as we've seen, was generally either tolerated or actively encouraged by local authorities; in any case, it was a predictable consequence of placing large numbers of police in tense circumstances, with neither the training nor the organization (not to mention to inclination) to respond with restraint.

While the Escalated Force model did not always produce police riots, it also did practically nothing to reduce the odds that they would occur. In one sense, the police riot can be understood as the last step in the Escalated Force sequence. During the sixties, three additional problems with Escalated Force became clear. First, the deployment of large numbers of cops often created a confrontation that could have otherwise been avoided. Second, the rigid enforcement of the law and the quick recourse to force provoked crowds and sometimes led to violence. And third, as a strategy for restoring order, Escalated Force failed [90].

Revising the Theory

Following the disasters of the late sixties, some people started to question the wisdom of a police strategy designed to "escalate" violence. Several commissions were set up to study the disturbances of the sixties, their causes, and the police response to them. Most prominent among these were the Kerner, Eisenhower, and Scranton commissions. All three bodies concluded that police actions against crowds often intensified, and in some cases provoked, civil disorder. They also recognized that the dangers of the Escalated Force model were not only tactical, but political.

The Scranton Commission wrote, "[T]o respond to peaceful protest with repression and brutal tactics is dangerously unwise. It makes extremists of moderates, deepens the divisions in the nation and increases the chances that future protests will be violent [91]."

Consequently, these boards recommended a number of changes in police handling of demonstrations. The Kerner Commission, for instance, advocated a strategy emphasizing manpower over firepower, prevention over reaction, and increased management and regimentation of the police. A new strategy, "Negotiated Management," was born.

Negotiated Management was designed to correct for the excesses of the Escalated Force model. Under the Negotiated Management approach,

Police do not try to prevent demonstrations, but attempt to limit the amount of disruption they cause.... Police attempt to steer demonstrations to times and places where disruption will be minimized.... Even civil disobedience, by definition illegal, is not usually problematic for police; they often cooperate with protesters when their civil disobedience is intentionally symbolic [92].

Under Negotiated Management, arrests are used only as a last resort, and force is kept to a strict minimum. Rather than trying to disperse the crowd, the police plan so as to contain it. Rather than responding to disorder with force, the police calculate their tactics so as to defuse potentially explosive situations. The innovation of this approach lies in the understanding that de-escalation is sometimes possible.

[T]he three most significant tactical tendencies characterizing protest policing in the 1990s appear to be (a) underenforcement of the law; (b) the search to negotiate; (c) large scale collection of information. [Beginning in the 1980s, police strategy was] dominated by the attempt to avoid coercive interaction as much as possible. Lawbreaking, which is implicit in several forms of protest, tends to be tolerated by the police. Law enforcement is usually considered as less important than peacekeeping. This implies a considerable departure from protest policing in the 1960s and 1970s, when attempts to stop unauthorized demonstrations and a law-and-order attitude in the face of the "limited rule-breaking" tactic used by the new movements maneuvered the police repeatedly into "no-win" situations [93].

Under the new model, police focus on preventing a disturbance, rather than responding to one, seeking to control demonstrations through a system of permits and a series of negotiations with protest organizers [94]. Elements such as the time of the event and the route of the march are agreed upon, and organizers are encouraged (or sometimes required) to provide their own marshals to exercise discipline over the group as a whole.

A model application of Negotiated Management is described by John Brothers in his article "Communication Is the Key to Small Demonstration Control." Brothers documents a series of anti-apartheid actions on the University of Kansas campus and details the Kansas University Police Department's response. Between April 29 and May 9, 1985, the campus was the site of three "moderate-sized" demonstrations and several small ones, including some accompanied by civil disobedience. Sixty-five arrests were made, but there were no injuries, no property damage, and no violence on either side. This small miracle was accomplished by establishing friendly relations with the demonstrators and being patient enough to let crowds dwindle on their own. Police kept their presence to a minimum and car fully crafted a non-aggressive demeanor (in part by not donning riot gear). They also provided refreshments on hot days, and waited to receive complaints before issuing citations. By these means, police won the cooperation of organizers, who met with them regularly to outline their plans [95].

Clearly this approach is better suited to a political system that espouses ideals of freedom and popular sovereignty, but the ultimate aim of Negotiated Management remains the same as that of Escalated Force (or even Maximum Force, before that) - to control dissent, to render protest ineffective.

Looking now at the Scranton, Eisenhower, and Kerner reports, what strikes the reader is the apparent schizophrenia of them all. They decry social injustice with criticisms of racial discrimination, prison conditions, and the plight of the urban poor. They push for greater inclusivity at all levels of society. But they also denounce the activities by which attention was successfully brought to these problems, and change effected. The Eisenhower report explicitly denounces civil disobedience; and, the Scranton report insists that those responsible for campus unrest be disciplined [96]. These reports push for rigorous adherence to Constitutional guarantees of free speech and the like, while at the same time offering precise instruction on the means of limiting, containing, and controlling protests.

It is tempting to read such documents as well-intentioned but politically naive defenses of the rule of law. But, rather more appropriately, one might also understand them as handbooks for social managers and others responsible for controlling dissent [97]. Taken as such, the reports' advocacy of civil liberties and the principle of minimal force reflect the sophistication of the liberal approach to repression. Negotiated Management was an innovation in the means of crowd control, but the basic aim remains unchanged. Both Negotiated Management and Escalated Force represent a defense of the status quo. Brothers' article, for example, emphasizes again and again the "neutrality" of the police, but notes that their plans were designed to "minimize the impact of the event upon the media [98]." Presumably, had the demonstrations aimed at goals besides media attention, the police would have sought to minimize their impact in those areas as well.

The Eisenhower Commission offers the Peace Moratorium March of November 15, 1969, as an example of the success of Negotiated Management:

The bulk of the actual work of maintaining the peacefulness of the proceedings was performed by the demonstrators themselves. An estimated five thousand "marshals," recruited from among the demonstrators, flanked the crowds throughout. Their effectiveness was shown when they succeeded in stopping an attempt by the fringe radicals to leave the line of the march in an effort to reach the White House.... [99]

The nature of such an arrangement is not lost on those who study law enforcement The academic literature describes marshals who "'police' other demonstrators [100]," and who have a "collaborative relationship" with the authorities [101]. This is essentially a strategy of co-optation. The police enlist the protest organizations to control the demonstrators, putting the organization at least partly in the service of the state and intensifying the function of control.

Playing by the Rules

The Negotiated Management model has its weaknesses as well. Its success requires a certain kind of cop and a certain kind of protest. If either is unavailable, Negotiated Management becomes impossible.

The Philadelphia police department made a very early attempt at this softer approach, and failed for lack of the right cop. In 1964, Police Commissioner Howard Leary created a "Civil Disobedience" unit charged with both keeping order and protecting the civil rights of demonstrators. This unit was to be headed by an officer proven to be calm, patient, and friendly. His job was to build a relationship with protest leaders and work with them to keep the peace. The unit never functioned as it was intended to. Instead, it quickly degenerated into a domineering red squad [101]. This quick return to the antagonistic approach was the result of several deeply rooted features of the police as a group, including the rejection of compromise and conciliatory tactics, an obsession with agitators and conspiracies, and the system of political sponsorship that guided promotion into the unit [103].

Police/protester cooperation requires a fundamental adjustment in the attitude of the authorities. The Negotiated Management approach demands the institutionalization of protest. Demonstrations must be granted some degree of legitimacy so they can be carefully managed rather than simply shoved about. This approach has, until recently, de-emphasized the radical or antagonistic aspects of protest in favor of a routinized and collaborative approach.

Naturally such a relationship brings with it some fairly tight constraints as to the kinds of protest activity available. Rallies, marches, polite picketing, symbolic civil disobedience actions, and even legal direct action - such as strikes or boycotts - are likely to be acceptable, within certain limits. Violence, obviously, would not be tolerated. Neither would property destruction. Nor would any of the variety of tactics that have been developed to close businesses, prevent logging, disrupt government meetings, or otherwise interfere with the operation of some part of society. That is to say, picketing may be fine, barricades are not. Rallies are in, riots are out. Taking to the streets - under certain circumstances - may be acceptable; taking over the factories is not. The danger, for activists, is that they might permanently limit themselves to tactics that are predictable, non-disruptive, and ultimately ineffective [104].

On the other side, Negotiated Management opens a pitfall for police where in they may come to rely on this cooperative arrangement. If the police assume that activists will conduct themselves within the bounds set by this approach, they leave themselves open for some nasty surprises.

Essentially, this is what happened to the Seattle police in 1999. According to the SPD's After Action Report, police planners adopted a Negotiated Management strategy early on and failed to consider contingencies that would make other options necessary. Despite well-publicized plans to disrupt the WTO conference, the police decided to "Trust that Seattle's strong historical precedents of peaceful protest and our on-going negotiations with protest groups would govern the actions of demonstrators [105]." On November 30, their mistake must have been only too obvious. When the institutional framework of protest was challenged, the cooperative relationship proved fragile and the basis of the Negotiated Management model was undermined. Not only did radicals refuse to play the game by its usual rules, even respectable protest groups were unable to keep their members in line. For example, when police changed the route of the officially sanctioned union march, hoping to keep union members away from the center of the disturbance, they were surprised when several thousand of the marchers ignored the marshals, left the route, and joined the fray [106].

The SPD offered this analysis of their mistake: "While we needed to think about a new paradigm of disruptive protest, we relied on our knowledge of past demonstrations, concluding that the 'worst case' would not occur here [107]." Such blindness is a typical fault of police agencies. Equally typical is the panic that follows a defeat - a panic felt not only in Seattle, but around the country, resulting in the sudden shift in police tactics at demonstrations nationwide.

Changes and learning processes of the police are initiated by an analysis of problematic public order interventions, that is, the police learn from their failures.... The importance of the body of past experience, however, seems such that it prevents the police from anticipating change. Tactical and strategic errors in confrontations with new movements and protest forms may trigger off a relapse into an antagonistic protest policing style [108].

In the wake of Seattle, the use of force has received a new emphasis. Riot gear, tear gas, mass arrests, and widespread violence have again become common features of demonstrations. While police violence has always been a possibility, it has lately come to resemble an open threat. Some of this is surely deliberate. The threat of violence is an effective tool for suppressing the attendance at a gathering, especially among portions of the population who are more routinely subject to police attack. It also serves to criminalize dissent. When members of the public see the police in riot gear, it is easy to assume that the crowd they are monitoring is dangerous, or even criminal [109]. But some of the police reliance on force is the product of desperation. They simply don't know what to do, and while they figure it out, the old-fashioned, straightforward head-knocking approach seems like a safe bet.

A Terrorist Strategy

The police and other authorities are frantically trying to find new footing in their handling of protests. Naturally, their mistakes in Seattle figure prominently in the developing analysis.

While everyone acknowledges that the police needed to be better prepared if they wanted to maintain control in Seattle, it is hotly disputed what, precisely, they should have been prepared for. The McCarthy report implies that the police should have been trained, armed, and organized as though to repel an invasion [110]. The city council's committee notes that the cops weren't even ready to implement the plan that they had and condemns the subsequent civil rights abuses and police violence. Essentially, the city council's committee thinks the problem was not with the Negotiated Management strategy, but with its implementation. They urged, not more force, but increased accommodation:

It is clear to the committee that demonstrators who sought arrest - in order to underline their statements of principle - should have been accommodated by police. Tear gas is a cruel implement to use against persons trying to make deeply-felt statements against what they view as injustice [111].

But the city council's perspective on this situation may rely on a misconception about what the protesters hoped to accomplish. Rather than seek symbolic arrests to "underline their statements of principle," protesters intended to directly interfere with the WTO's work by blockading the conference and disrupting its proceedings. The police didn't understand this until the disruption was underway; the city council seems never to have figured it out.

The McCarthy and Associates report implies that where Negotiated Management failed on November 30, Escalated Force succeeded on December 1. If this is true, then the lesson the police should take from Seattle is that the Negotiated Management model is one strategy of control, but that to rely on it exclusively is to court disorder. The use of force must always be prepared for, if only as a backup. The LAPD has adopted just such a two-track approach, alternating between Negotiated Management and Escalated Force strategies according to the circumstances. Two incidents from the 2000 Democratic National Convention suffice to make the case:

On August 14, after a concert in one of the designated protest areas [112], police cut power to the stage, declared the event an unlawful assembly, and gave approximately 10,000 people twenty minutes to leave through a single exit. A short time later, the cops attacked, charging with horses and firing rubber bullets. The Los Angeles Times reported, "In addition to rubber bullets, police also used pepper spray and projectile beanbags, striking many of the protesters and some bystanders as they fired indiscriminately for more than an hour [113]." Jesse Jackson termed the police action "unnecessary brutality"; Commander David Kalish called it "a measured, strategic response [114]." They may both be right. The ACLU described the event precisely, referring to it as "an orchestrated police riot [115]."

A few days later, the cops showed a different face when thirty- seven people sat down in front of the notorious Rampart Division police station and refused to leave.

The civil disobedience action ... attempted to focus on the brutality, corruption, and violence of the LAPD.... However, some of the organizers had collaborated closely with the Rampart police prior to the action to work out the details of the arrests, and had followed some suggestions of the police in order to avoid what they feared would be the cops going berserk if taken by surprise. After presenting the police chief with a list of demands, one of the arrestees shook hands amicably with him as the cameras flashed. Ironically, the result was a PR/media opportunity to showcase the civility and non-violent behavior of the cops [116].

This incident shows the effective co-optation of protest when it proceeds through collaborative channels. It also shows the disciplining effect of police violence: the threat of violence motivates protesters to negotiate ahead of time, and allows the cops to set the rules. As per the McCarthy team recommendations, a hybrid approach may incorporate Escalated Force as the primary strategy of control, with Negotiated Management serving as a tool for police to establish boundaries. This approach works as a modification of the Good Cop/Bad Cop routine: if the Bad Cop is bad enough, he may only need to act in minor or symbolic ways to keep the crowd in line. Negotiation with the Good Cop starts to look more attractive, as does playing by the rules. This, in essence, is the strategy of political terrorism. The threat of violence is made clear at every turn, and a politically useful climate of fear is carefully developed in order to control the population [117]. Terrorism and co-optation are thus subsumed under a single system.

This is something we should learn to expect: the strategic use of both the Good Cop and the Bad Cop to control and, ultimately, to neutralize dissent.

Organizational Changes

If the 2000 Democratic Convention is any indication, it would seem that the biggest change since 1968 is the broadened range of tactics available to police. Police commanders have gained the ability to restrain officers when a Good Cop approach is in order. This is made possible by organizational changes connected, both historically and conceptually, to the process of militarization.

Historically, the federal government prompted the development of Negotiated Management: the approach was shaped by the various commission reports, Supreme Court rulings, the development of the National Park Service permit system, and the availability of crowd control training at the U.S. Army Military Police School [118]. (In this respect, local police have followed a course similar to that of the National Guard, which was militarized after the 1877 strike wave.) This new training was specifically designed according to the recommendations of the Kerner and Eisenhower reports [119].

The Negotiated Management model arose at the same time and from the same sources as the militarization of the police. To make sense of this, it is important to understand that militarization does not only refer to police tactics and weaponry, but also to their mode of organization. 120 The Kerner report argued for it explicitly:

The control of civil disturbances ... requires large numbers of disciplined personnel, comparable to soldiers in a military unit, organized and trained to work as a team under a highly unified command and control system. Thus when a civil disturbance occurs, a police department must suddenly shift into a new type of organization with different operational procedures. The individual officer must stop acting independently and begin to perform as a member of a closely supervised, disciplined team [121].

In short, it is military discipline that makes Negotiated Management a possibility, restraining the individual officers while maintaining the potential for a coordinated attack. This requires careful planning for the operation itself, and a high level of discipline among the officers so that each one acts according to the established plan [122]. Hence, militarization may increase the organization's overall capacity for violence, but may decrease individual acts of brutality, owing to a higher level of discipline [123].

Previously, individual acts of brutality were tolerated or encouraged as a means of controlling the population through terror. But this approach can be limiting, as it renders negotiation and co-optation unlikely. Militarization formalizes the strategy of violence at the institutional level. It thus maintains discipline and employs force more selectively, with direction from above.

Ironically, while the conventional wisdom associates militarization with the Escalated Force approach, in point of fact militarization is essential to Negotiated Management [124]. Moreover, as we shall see, militarization is a key component of community policing.