- Return to book

- Review this book

- About the author

- Publishing Info

- 1. Contents

- 2. Acknowledgments

- 3. Introduction by Joy James

- 4. Author's Preface, 2007

- 5. Foreword: Police and Power in America

- 6. One: Police Brutality in Theory and Practice

- 7. Two: The Origins of American Policing

- 8. Three: The Genesis of a Policed Society

- 9. Four: Cops and Klan, Hand in Hand

- 10. Five: The Natural Enemy of the Working Class

- 11. Six: Police Autonomy and Blue Power

- 12. Seven: Secret Police, Red Squads, and the Strategy of Permanent Repression

- 13. Eight: Riot Police or Police Riots?

- 14. Nine: Our Friendly Neighborhood Police State

- 15. Afterword: Making Police Obsolete

- 16. Notes

- 17. Selected Bibliography

- 18. Index

- 19. About the Author

1

Police Brutality in Theory and Practice

In April 2001, when police officer Stephen Roach killed Timothy Thomas, Cincinnati served as the stage for a classic American drama. Thomas, an unarmed teenager wanted for several misdemeanor warrants, was the fifteenth Black man the Cincinnati police had killed in six years [1]. A few days later, protesters led by the victim's mother occupied City Hall for three hours. When they were forced out, the crowd marched to the police station, growing as it went. At the police station, the demonstration escalated. Members of the crowd hit the cops with rocks and bottles, shattered the station's glass entryway, and removed the American flag outside. When the police responded with tear gas and rubber bullets, the disorder spread [2]. For three nights, hundreds of people, mostly young Black men, participated in looting and vandalism [3]. The rioting mostly consisted of window-breaking and sporadic attacks on White people, though dumpster fires became so common that the fire department stopped responding to them [4]. The fight was by no means one-sided. The police made 760 arrests and injured an unknown number of people [5].

In what was perhaps the most disgraceful episode of the entire affair, police fired seven less-lethal "beanbags" at a crowd gathered for Thomas's funeral service. Four people were hit, including two children. One victim, Christine Jones, was hospitalized with a fractured rib, bruised lung, and injured spleen. She described the incident: "It was like a drive-by shooting. All of a sudden, out of the blue, several police cars screeched to a halt at [the] intersection, jumped out of cars and just immediately started shooting people with the shotguns. No warning. No nothing [6]."

It's no secret that the police come into conflict with members of the public. The police are tasked with controlling a population that does not always respect their authority and may resist efforts to enforce the law. Hence, police are armed, trained, and authorized to use force in the course of executing their duty. At times, they use the ultimate in force, killing those they are charged with controlling.

Under such an arrangement, it is not surprising that officers sometimes move beyond the bounds of their authority. Nor is it surprising that the affected communities respond with anger - sometimes rage. The battles that ensue do not only concern particular injustices, but also represent deep disputes about the rights of the public and the limits of state power. On the one side, the police and the government try desperately to maintain control, to preserve their authority. And on the other, oppressed people struggle to assert their humanity. Such riots represent, among other things, the attempt of the community to define for itself what will count as police brutality and where the limit of authority falls. It is in these conflicts, not in the courts, that our rights are established.

The Rodney King Beating: "Basic stuff really"

On March 3, 1991, a Black motorist named Rodney King led the California Highway Patrol and the Los Angeles Police Department on a ten-minute chase. When he stopped and exited the car, the police ordered him to lie down; he got on all fours instead, and Sergeant Stacey Koon shot him twice with an electric taser. The other passengers in King's car were cuffed and laid prone on the street. An officer kept his gun aimed at them, and when they heard screams he ordered them not to look. One did try to look, and was clubbed on the head [7].

Others were watching, however, and a few days later the entire world saw what had happened to Rodney King. A video recorded by a bystander shows three cops taking turns beating King, with several other officers looking on, and Sergeant Stacey Koon shouting orders. The video shows police clubbing King fifty-six times, and kicking him in the body and head [8]. When the video was played on the local news, KCET enhanced the sound. Police can be heard ordering King to put his hands behind his back and calling him "nigger [9]."

The chase began at 12:40 A.M. and ended at 12:50 A.M. At 12:56, Sgt. Koon reported via his car's computer, "You just had a big time use of force... tased and beat the suspect of CHP pursuit, Big Time." At 12:57, the station responded, "Oh well ... I'm sure the lizard didn't deserve it ... HAHA." At 1:07, the watch commander summarized the incident (again via Mobile Data Terminal): "CHP chasing ... failing to yield ... passed [car] A 23 ... they became primary ... then tased, then beat ... basic stuff really [10]." Koon himself endorsed this assessment of the incident. In his 1992 book on the subject, he described the altercation with Rodney King as unexceptional: "Just another night on the LAPD. That's what it had been [11]."

King was jailed for four days, but released without charges. He was treated at County-USC Hospital, where he received twenty stitches and treatment for a broken cheekbone and broken ankle. Nurses there reported hearing officers brag and joke about the beating. King later listed additional injuries, including broken bones and teeth injured kidneys, multiple skull fractures, and permanent brain damage [12].

Twenty-three officers had responded to the chase, including two in a helicopter. Of these, ten Los Angeles Police Department officers were present on the ground during the beating, including four field training officers, who supervise rookies. Four cops - Stacey Koon, Laurence Powell, Timothy Wind, and Theodore Briseno - were indicted for their role in the beating. Wind was a new employee, still in his probationary period, and was fired. The two California Highway Patrol officers were disciplined for not reporting the use of force, and their supervisor was suspended for ten days. But none of the other officers present were disciplined in any way, though they had done nothing to prevent the beating or to report it afterward [13].

The four indicted cops were acquitted. Social scientists have argued that the verdict was "predictable," given the location of the trial. As Oliver, Johnson, and Farrel write:

Simi Valley, the site of the trial, and Ventura County more generally, is a predominantly white community known for its strong stance on law and order, as evidenced by the fact that a significant number of LAPD officers live there. Thus, the four white police officers were truly judged by a jury of their peers. Viewed in this context, the verdict should not have been unanticipated [14].

Koon, Powell, Wind, and Briseno were acquitted. They were then almost immediately charged with federal civil rights violations, but that was clearly too little, too late. L.A. was in flames.

A Social Conflagration

The people of Los Angeles offered a ready response to the acquittal. Between April 30 and May 5, 1992, 600 fires were set [15]. Four thousand businesses were destroyed [16], and property damage neared $1 billion[17]. Fifty-two people died, and 2,383 people were injured seriously enough to seek medical attention [18]. Smaller disturbances also erupted around the country - in San Francisco, Atlanta, Las Vegas, New York, Seattle, Tampa, and Washington, D.C. [19].

Despite the media's portrayal of the riot as an expression of Black rage, arrest statistics show it to have been a multicultural affair: 3,492 Latinos, 2,832 Black people, and 640 White people were arrested, as were 2,492 other people of unidentified races [20]. Likewise, despite the media focus on violence (especially attacks on White people and Korean merchants), the data tell a different story. Only 10 percent of arrests were for violent crime. The most common charge was curfew violation (42 percent), closely followed by property crimes (35 percent) [21]. Likewise, the actual death toll

definitely attributable to the rioters was under twenty. The police killed at least half that many, and probably many more ... Moreover, although some whites and Korean Americans were killed, the vast majority of fatalities were African Americans and Hispanic Americans who died as bystanders or as rioters opposing civil authorities [22].

Depending on whom you ask, you will hear that the riots constituted "a Black protest," a "bread riot," the "breakdown of civilized society," or "interethnic conflict" [23]. None of these accounts is sufficient on its own, but one thing is certain: the riots speak to conditions beyond any single incident.

In the five years preceding the Rodney King beating, 2,500 claims relating to the use of force were filed against the LAPD [24]. To describe just one: In April 1988, Luis Milton Murrales, a twenty-four-year-old Latino man, lost the vision in one eye because of a police beating. That incident also began with a traffic violation, followed by a brief chase. Murrales crashed his car into a police cruiser and tried to flee on foot. The police caught him, clubbed him, and kicked him when he fell. They resumed the beating at the Rampart station; the attack involved a total of twenty-eight officers. One commander described his subordinates as behaving like a "lynch mob." Though the city paid $177,500 in a settlement with Murrales, none of the officers was disciplined [25]."

Such incidents, as well as the depressed economic conditions of the inner city, supplied the fuel for a major conflagration. The King beating, the video, and the verdict offered just the spark to set it off [26].

A Lesson to Learn, And Learn Again

Rodney King's beating was unusual only because it was videotaped. The community that revolted following the acquittal seemed to grasp this fact, even if the learned commentators and pious pundits condemning them did not. By the same token, the revolt itself also fit an established pattern.

In 1968, the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (commonly called the Kerner Commission) examined twenty-four riots and reached some remarkable conclusions:

Our examination of the background of the surveyed disorders revealed a typical pattern of deeply-held grievances which were widely shared by many members of the Negro community. The specific content of the expressed grievances varied somewhat from city to city But in general, grievances among Negroes in all cities related to prejudice, discrimination, severely disadvantaged living conditions and a general sense of frustration about their inability to change those conditions.

Specific events or incidents exemplified and reinforced the shared sense of grievance.... With each such incident, frustration and tension grew until at some point a final incident, often similar to the incidents preceding it, occurred and was followed almost immediately by violence.

As we see it, the prior incidents and the reservoir of underlying grievances contributed to a cumulative process of mounting tension that spilled over into violence when the final incident occurred. In this sense the entire chain - the grievances, the series of prior tension-heightening incidents, and the final incident - was the "precipitant" of disorder [27].

The Kerner report goes on to note, "Almost invariably the incident that ignites disorder arises from police action. Harlem, Watts, Newark, and Detroit - all the major outbursts of recent years - were precipitated by routine arrests of Negroes for minor offenses by white officers [28]."

A few years earlier, in his essay "Fifth Avenue, Uptown: A Letter from Harlem," James Baldwin had offered a very similar analysis:

[T]he only way to police a ghetto is to be oppressive. None of the Police Commissioner's men, even with the best will in the world, have any way of understanding the lives led by the people they swagger about in twos and threes controlling. Their very presence is an insult, and it would be, even if they spent their entire day feeding gumdrops to children. They represent the force of the white world, and that world's real intentions are, simply, for that world's criminal profit and ease, to keep the black man corralled up here, in his place... One day, to everyone's astonishment, someone drops a match in the powder keg and everything blows up. Before the dust has settled or the blood congeals, editorials, speeches, and civil-rights commissions are loud in the land, demanding to know what happened. What happened is that Negroes want to be treated like men [29].

Baldwin wrote his essay in 1960. Between its publication and that of the Kerner report, the U.S. witnessed civil disturbances of increasing frequency and intensity. Notable among these was the Watts riot of 1965. The Watts rebellion has been said to divide the sixties into its two parts - the classic period of the civil rights movement before, and the more militant Black Power movement after [30].

Like the riots of 1992, the Watts disturbance began with a traffic stop. Marquette Frye was pulled over by the California Highway Patrol near Watts, a Black neighborhood in Los Angeles. A crowd gathered, and the police called for backup. As the number of police and bystanders grew, the tension increased accordingly. The police assaulted a couple of bystanders and arrested Frye's family. As the cops left, the crowd stoned their cars. They then began attacking other vehicles in the area, turning them over, and setting them on fire. The next evening, the disorder arose anew, with looting and arson in the nearby commercial areas. The riot lasted six days and caused an estimated $35 million in damage. Almost 1,000 buildings were damaged or destroyed. One thousand people were treated for injuries, and thirty-four were killed [31].

Fourteen years after Watts, and thirteen years before the Rodney King verdict, a similar drama played out on the other side of the country, in Miami. On December 17, 1979, the police chased, caught, beat, and killed a Black insurance salesman named Arthur McDuffie. McDuffie, who was riding his cousin's motorcycle, allegedly popped a wheelie and made an obscene gesture at Police Sergeant Ira Diggs, before leading police on an eight-minute high speed chase. Twelve other cars joined in the pursuit, and when they caught McDuffie, between six and eight officers beat him with heavy flashlights as he lay handcuffed, face down on the pavement. Four days later, he died [32].

Three officers were charged with second-degree murder, and three others agreed to testify in exchange for immunity. Judge Lenore Nesbitt called the case "a time bomb" and moved it to nearby Tampa, where an all-White jury had recently acquitted another officer accused of beating a Black motorist [33]. The defense then used its peremptory challenges to remove all Black candidates from the jury. The outcome was predictable: the cops were acquitted [34], crowds then looted stores, burned buildings, and attacked White passers-by. Crowds also laid siege to the police station, breaking its windows and setting fire to the lobby [35]. When calm returned, seventeen people were dead, 1,100 had been arrested, and $80 million in property had been damaged [36]. Four hundred seventeen people were treated in area hospitals, the majority of them White [37].

Here was a key difference: in Miami, the typical looting and burning of White-owned property were matched with attacks against White people. In the disorders of the 1960s, attacks against persons had been relatively rare. In three of the sixties' largest riots - those of Watts, Newark, and Detroit - the crowd intentionally killed only two or three White people. Bruce Porter and Marvin Dunn comment:

What was shocking about Miami was the intensity of the rage directed against white people: men, women and children dragged from their cars and beaten to death, stoned to death, stabbed with screwdrivers, run over with automobiles; hundreds more attacked in the street and seriously injured.... In Miami, attacking and killing white people was the main object of the riot [38].

Among those injured in the riots was an elderly White man named Martin Weinstock. Weinstock was hit in the head with a piece of concrete and suffered a fractured skull. He was hospitalized for six days. Still, he told an interviewer:

They should only know that I agree with their anger.... If the people who threw the concrete were brought before me in handcuffs, I would insist that the handcuffs be removed, and I'd try to talk to them. I would say that I understand and that I'm on their side. I have no anger at all. But they'll never solve their problems by sending people like me to the hospital [39].

Weinstock is right: violence directed against random representatives of some dominant group is hardly strategic, much less morally justifiable. But if such attacks are (as Porter and Dunn insist) "shocking, " it can only be because Black anger has so rarely taken this form.

White violence against Black people has never been limited to the destruction of their property. Even in Miami, Black people got the worst of the violence. Of the seventeen dead, nine were Black people killed by the police, the National Guard, or White vigilantes [40]. Are these deaths somehow less shocking than those of White people?

Yet - how loudly White people denounce prejudice when it is directed against them, and how quietly they accept it as it continually bears down on people of color. They indignantly point out the contradiction when those who object to prejudice employ it, and all the while adroitly ignore their own complicity in the institutions of White supremacy.

James Baldwin, again in his "Letter from Harlem, " imagines the predicament of a White policeman patrolling the ghetto: "He too believes in good intentions and is astounded and offended when they are not taken for the deed. He has never, himself, done anything for which to be hated.... But, "Baldwin asks, "which of us has [41]?"

The Basics

We are encouraged to think of acts of police violence more or less in isolation, to consider them as unique, unrelated occurrences. We ask ourselves always, ''What went wrong?" and for answers we look to the seconds, minutes, or hours before the incident. Perhaps this leads us to fault the individual officer, perhaps it leads us to excuse him. Such thinking, derived as it is from legal reasoning, does not take us far beyond the case in question. And thus, such inquiries are rarely very illuminating.

Of the instances of police violence I discussed above - the shooting of Timothy Thomas, the beatings of Rodney King and Luis Milton Murrales, the arrest of Marquette Frye, the killing of Arthur McDuffie - any of these may be explained in terms of the actions and attitudes of the particular officers at the scene, the events preceding the violence (including the actions of the victims), and the circumstances in which the officers found themselves. Indeed, juries and police administrators have frequently found it possible to excuse police violence with such explanations.

The unrest that followed these incidents, however, cannot be explained in such narrow terms. To understand the rioting, one must consider a whole range of related issues, including the conditions of life in the Black community, the role of the police in relation to that community, and the history and pattern of similar abuses.

If we are to understand the phenomenon of police brutality, we must get beyond particular cases. We can better understand the actions of individual police officers if we understand the institution of which they are a part. That institution, in turn, can best be examined if we have an understanding of its origins, its social function, and its relation to larger systems like capitalism and White supremacy. Each of these topics will be addressed in later chapters, while here, as a first course, I will focus on what is known about police violence per se.

Let's begin with the basics: violence is an inherent part of policing. The police represent the most direct means by which the state imposes its will on the citizenry [42]. When persuasion, indoctrination, moral pressure, and incentive measures all fail - there are the police. In the field of social control, police are specialists in violence. They are armed, trained, and authorized to use force. With varying degrees of subtlety, this colors their every action. Like the possibility of arrest, the threat of violence is implicit in every police encounter. Violence, as well as the law, is what they represent.

Defining Brutality

The study of police brutality faces any number of methodological barriers, not the least of which is the problem of defining it. There is no standard definition, nor is there one way of measuring force and excessive force. As a consequence, different studies produce very different results, and these results are difficult to compare. Kenneth Adams, writing for the National Institute of Justice, notes:

Because there is no standard methodology for measuring use of force, estimates can vary considerably on strictly computational grounds. Different definitions of force and different definitions of police-public interactions will yield different rates.... In particular, broad definitions of use of force, such as those that include grabbing or handcuffing a suspect, will produce higher rates than more conservative definitions.... Broad definitions of police-public "interactions," such as calls for assistance, which capture variegated requests for assistance, lead to low rates of use of force. Conversely, narrow definitions of police-public interactions, such as arrests, which concentrate squarely on suspects, lead to higher rates of use of force [43].

Adams himself outlines multiple definitions for use-of-force violations, focusing on different aspects of the misconduct.

For example, "deadly force" refers to situations in which force is likely to have lethal consequences for the victim. [The victim need not necessarily die.] ... [T]he term "excessive force" is used to describe situations in which more force is used than allowable when judged in terms of administrative or professional guidelines or legal standards .... "Illegal" use of force refers to situations in which use of force by police violated a law or statute.... "Improper," "abusive," "illegitimate," and "unnecessary" use of force are terms that describe situations in which an officer's authority to use force has been mishandled in some general way, the suggestion being that administrative procedure, societal expectations, ordinary concepts of lawfulness, and the principle of last resort have been violated, respectively [44]."

Adding to the difficulty of comparing one set of figures with another, each of these concepts refers to standards that vary according to the agency, jurisdiction, and community involved. Even within a single agency, agreement on the interpretation of the relevant standards may not be perfect Bobby Lee Cheatham, a Black cop in Miami, noted the different standards among the police: 'To [white officers], police brutality is going up and just hitting on someone with no reason.... To me, it's when a policeman gets in a situation where he's too aggressive or uses force when it isn't needed. Most of the time the policeman creates the situation himself [45]."

Even where the facts of a case are agreed upon (which is rare), there may yet be intense disagreement about the relevant standards of conduct and their application to the particular circumstances. For example, in October 1997, sheriff's deputies in Humboldt County, California, swabbed pepper-spray fluid directly into the eyes of non-violent anti-logging demonstrators locked together in an act of civil disobedience. Amnesty International called the tactic "deliberately cruel and tantamount to torture." A federal judge refused to issue an injunction against the practice, however, claiming that it only caused "transient pain [46]."

This case highlights the disparate judgments possible, even given the same facts. A great many people feel about police brutality as Justice Potter Stewart felt about pornography: they can't define it, but they know it when they see it. Unfortunately, they might not know it when they see it. Many police tactics - the use of pressure points, the fastening of handcuffs too tightly, and the direct application of pepper spray, for example - really don't look anything like they feel. More to the point, in most cases, nobody sees the brutality at all, except for the cops and their victims. The rest of us have to rely on secondary information, usually taking one side or the other at their word.

Things get even stickier when general patterns of violence are scrutinized, even where no particular encounter rises to the level of official misconduct "Use of excessive force means that police applied too much force in a given incident, while excessive use of force means that police apply force legally in too many incidents [47]." While the former is more likely to grab headlines, it is the latter that makes the largest contribution to the community's reservoir of grievances against the police. But, since the force in question is within the bounds of policy, the excessive use of force is more difficult to address from the perspective of discipline and administration.

All of this controversy and confusion points to a very simple fact: police brutality is a normative construction. It involves an evaluation, a judgment, and not simply a collection of facts. David Bayley and Harold Mendelsohn explain:

It should also be noted that police brutality is not just a descriptive category. Rather it is a judgment made about the propriety of police behavior.... Since the use of the phrase implies a judgment, people may disagree profoundly about whether a particular incident, even though it involves the obvious use of force, is a case of brutality.

Any discussion of police brutality is therefore encumbered by confusion about whether it applies to more than physical assaults and also by disagreement over what circumstances absolve the police from blame [48].

In short, the technical distinctions between, say, excessive force and illegal force, while bringing some measure of precision to the discussion, lead us no nearer to a resolution of these disputes. That's because, at root, the disagreement is not about whether a rule was broken, or a law violated. The question - the real question - is one of legitimacy. The larger conflict is a conflict of values.

Let's consider this problem anew: the trouble, or part of it, comes in discerning the legitimate and illegitimate uses of violence. Abuses of authority may look very much like their less corrupt counterparts. Or, stated from a different perspective, the application of legitimate force often feels quite a lot like abuse. But there is no paradox here, not really. The state, claiming a monopoly on the legitimate use of force, needs to distinguish its own violence from other, allegedly less legitimate, uses of force. In nontotalitarian societies, authority exists within carefully prescribed, if vague (one might suggest, intentionally vague), boundaries. Action within these limits is "legitimate," similar action outside of such limits is "abuse." It's as simple as that. If the difference seems subtle, that's because it is subtle. In the case of police violence, the difference between legitimate and excessive force is one of degree rather than one of kind. (Even the term "excessive force" implies this.) Hence, where you or I see brutality, the cop sees only a day's work. The authorities - the other authorities - more often than not side with the policeman, even where he has violated some law or policy. This is, in a sense, only fair, since the police officer - unless he engages in mutiny - always sides with them. The main difference, then, between policing and police abuse is a rule or law that usually goes unenforced. The difference is the words.

Why We Know So Little About Police Brutality

The preceding observations provide a framework for understanding police brutality, but tell us almost nothing about its prevalence, its forms, its perpetrators, or its victims. Solid facts and hard numbers are very hard to come by.

This dearth of information may say something about how seriously the authorities take the problem. Until very recently, nobody even bothered to keep track of how often the police use force - at least not as part of any systematic, national effort. In 1994, Congress decided to require the Justice Department to collect and publish annual statistics on the police use of force. But this effort has been fraught with difficulty. Unlike the Justice Department's other major data-collection projects - the Uniform Crime Reports provide a useful contrast - the examination of police use of force has never received adequate funding, and the reports appear at irregular intervals. Furthermore, the data on which the studies are based are surely incomplete. Many of the reports rely on local police agencies to supply their numbers, and reporting is voluntary [49]." Worse, the information, once collected and analyzed, is often put to propagandistic uses; its presentation is sometimes heavily skewed to support a law enforcement perspective. But despite their many flaws, the Justice Department reports remain one of the most comprehensive sources of information about the police use of force.

These reports represent various approaches to the issue. They measure the use of force as it occurs in different circumstances, such as arrests and traffic stops. They examine both the level of force used and the frequency with which it is employed. And some studies collect data from victims as well as police.

Unfortunately, under-reporting handicaps every means of compiling the data. One report states frankly: "The incidence of wrongful use of force by police is unknown.... Current indicators of excessive force are all critically flawed [50]." The most commonly cited indicators are civilian complaints and lawsuits. But few victims of police abuse feel comfortable complaining to the same department under which they suffered the abuse, and lawyers usually only want cases that will win - in other words, cases where the evidence is clear and the harm substantial. Many people fail to make a complaint of any kind, either because they would like to put the unpleasant experience behind them, because they fear retaliation, because they suspect that nothing can be done, or because they feel they will not be believed [52]. Hence, measures that depend on victim reporting are likely to represent only a small fraction of the overall incidence of brutality.

According to a 1999 Justice Department survey, "The vast majority (91.9 percent) of the persons involved in use of force incidents said the police acted improperly.... Although the majority of persons with force [used against them] felt the police acted improperly, less than 20 percent of these people ... said they took formal action such as filing a complaint or lawsuit.... [53]" Naturally, the victim is not always the best judge as to whether force was excessive, but in some cases, he may be the only source willing to admit that force was used at all. This provides another reason to separate questions concerning the legitimacy of violence from those concerning its prevalence.

The difficulties in measuring excessive and illegal force with complaint and lawsuit records have led academics and practitioners to redirect their attention to all use-of-force incidents. The focus then becomes one of minimizing all instances of police use of force, without undue concern as to whether force was excessive. From this perspective, other records, such as use-of-force reports, arrest records, injury reports, and medical records, become relevant to measuring the incidence of the problem [54].

Of course, these indicators also have their shortcomings. Arrest records, medical records, and the like will surely reveal uses of violence that have not resulted in lawsuits or formal complaints. But they will still underestimate the overall incidence of force, since not every case will be accurately recorded. For example, attempts to assess the prevalence of force based on arrest reports leave out those cases where force was used but no arrest was made [55]. Like the victims (though for very different reasons), the perpetrators of police violence are also likely to under-report its occurrence. And they are likely to understate the level of force used and the seriousness of resultant injuries when they do report it [56]. Individual medical records, meanwhile, are not generally available for examination, except when presented as evidence in a complaint hearing or civil trial. And even if emergency rooms were to main tain statistics on police-related injuries, many victims of violence, especially the uninsured, do not seek treatment except for the most serious of injuries.

Other indicators, such as media reports and direct observation, are similarly flawed. The media, of course, can only report on events if they know about them. Furthermore, they are unlikely to report on routine uses of force because - like the fabled "Dog Bites Man" story - it is so commonplace [57]. Direct observation is limited by the obvious fact that no one can observe everything, everywhere, all the time. And observation can lead a subject (either the officer or the suspect) to change his behavior while he is being observed. In humanitarian terms, such deterrence is all for the good, but it doesn't do much for the systematic study of police activity or the measurement of police violence.

The sad fact is that nobody knows very much about the police use of force, much less about the use of excessive force. Its prevalence, frequency, and distribution remain, for the most part, unmeasured; and there is only limited information available concerning its perpetrators, victims, forms, and causes. Nevertheless, some information is available through the sources mentioned above. And, imperfect though they are, the statistics they produce may point to a reliable baseline, an estimated minimum to which we can refer with a fair amount of certainty. With that aim in mind, and with not a little trepidation, we should turn our attention to the data that are available, and consider what they indicate.

A Look at the Numbers

According to a 1996 Justice Department survey, 20 percent of the American public had direct contact with the police during the previous year. Most of these contacts took the form of traffic stops, and most were unremarkable. Only 1 in 500 residents was subject to the use of force or the threat of force. Three years later, the Justice Department repeated the study, this time with a sample almost fifteen times as large. The results were nearly identical: 21 percent of the population had contact with the police in 1999, and 1 in 500 fell victim to violence or threats of violence [58].

Now, that may not sound like a lot of people, until you realize that "1 in 500" is a polite way of saying "nearly half a million" - an estimated 471,000 people in 1996 and 422,000 in 1999 [59]. Four hundred thousand people, if we got them all together, would make for a fair-sized city, larger than Atlanta, Georgia, and almost as large as Fresno, California [60]. And when you orient yourself to the fact that this city could be reproduced every year, you start to get some picture of how common police violence really is. Another way of looking at the figures is that, out of every 100 people the police come into contact with, they will threaten or use force against one of them (0.96 percent) . This rate is nearly twice as high for Black people and Latinos, who experience force (or the threat thereof) in 2 percent of their interactions with the police [61].

Among these 422,000 people, the most common form of violence they suffered involved being pushed or grabbed [62]. Approximately 20 percent were threatened, but not subject to actual physical violence. At the other end of the curve, another 20 percent reported injuries [63]. More than three-quarters of the victims (76 percent) characterized the force as excessive [64], and the "vast majority (92 percent) of persons experiencing [the] threat or use of force said the police acted improperly [65].

According to a Justice Department study of six police agencies [66], police use force in 17.1 percent of all adult custody arrests (or 18.9 percent, if we include threats of force). Suspects, in contrast, use force against the police in less than 3 percent of arrest cases. More specifically, suspects employ weaponless tactics in 1.9 percent of arrests, and use weapons in 0.7 percent. Police, meanwhile, use weaponless tactics in 15.8 percent of arrests, and use weapons in about 2.1 percent [67]. The police, in short, use force far more often than it is used against them.

With police using force in about one of every six arrests, it strikes me as an inescapable fact that police violence is quite routine, but most studies resist this conclusion, insisting that the use of force is exceptional [68]. The police themselves seem untroubled by the level of violence within their departments. According to a National Institute of Justice study on "Police Attitudes Toward Abuse of Authority, "24.5 percent of police surveyed "agreed" or "strongly agreed" that "It is sometimes acceptable to use more force than is legally allowable to control someone who physically assaults an officer"; 31.1 percent contended that "Police are not permitted to use as much force as is often necessary in making arrests"; and 42.2 percent felt that "Always following the rules is not compatible with getting the job done [69]."

Interestingly, 62.4 percent of police feel that officers in their department "seldom" "use more force than is necessary to make an arrest." Sixteen percent maintained that police never do, and 21.7 percent said that police sometimes, often, or always use excessive force [70]. Sociologist Rodney Stark (writing well before the study in question) explained this tendency to understate the incidence of violence: "[If] each policeman only loses his temper once or twice a year and roughs someone up, a very large number of citizens will get roughed up during the year. Thus, their violence may seem occasional to individual policemen, when in fact for the force as a whole it is routine [71]."

Of course, the propensity for violence is not distributed evenly throughout police departments. The Independent Commission on the Los Angeles Police Department (also called the Christopher Commission) noted:

Of nearly 6,000 officers identified as involved in a use of force ... from January 1987 through March 1991, more than 4,000 had less than five reports each. But 63 officers had 20 or more reports each. The top 5 percent of officers ranked by number of reports accounted for more than 20 percent of all reports, and the top 10 percent accounted for 33 percent [72].

These numbers may not be as comforting as they first seem. For one thing, 6,000 cops is still quite a lot, even when the occasions of their violence are spread over four years. In fact, it seems the Christopher Commission fell into precisely the trap that Rodney Stark described: by emphasizing the idea that most officers rarely use force, they demonstrate that brutality is individually rare, while obscuring the fact that it is collectively common. Four thousand officers, with fewer than five reports each, together could have nearly 20,000 such reports. Moreover, the unruly 5 percent, in numerical terms, would add up to about 300 officers [73]. One retired LAPD sergeant told the Christopher Commission that there were at least one or two cops in every division who regularly use excessive force [74], This would imply that not only is brutality routine, it is widespread.

But, however common police brutality may be, its victims are not a perfect cross-section of the American public. In 1999, for example, 86.9 percent of the victims of police violence were male, and 55.3 percent were between the ages of sixteen and twenty-four [75]. While most victims were White (58.9 percent), Black people and Latinos were victimized in numbers significantly out of proportion to their representation in the general population. Latinos make up 10.2 percent of the population nationally, but accounted for 15.5 percent of those victimized by the police. Black people constitute 11.4 percent of the population, and 22.6 percent of those facing police violence [76]. Of those killed by police from 1976 to 1998, 42 percent were Black [77].

These figures, which I have recited with relatively little comment, offer only a very limited representation of police violence. The studies producing these numbers, with their statistics and their charts, seem altogether too sanitized. They should, to do the subject justice, come smeared with blood, with numbers surrounded by chalk outlines. The real cost of police violence, the human cost, is too easily forgotten, figured away, buried under a mountain of decimal points. We must not allow that to happen. We must bear in mind, always, that each of these statistics represents a tragedy. Behind each there lies real pain, humiliation, indignity, often injustice, and sometimes death. Our understanding of police brutality relies on our ability to hear the scream behind the statistic. Once we do, the rage of L.A, of Miami, of Cincinnati becomes comprehensible. Their fires may burn inside us.

Explaining Away the Abuse

In Uprooting Racism, Paul Kivel makes a useful comparison between the rhetoric abusive men employ to justify beating up their girlfriends, wives, or children and the publicly traded justifications for widespread racism. He writes:

During the first few years that I worked with men who are violent I was continually perplexed by their inability to see the effects of their actions and their ability to deny the violence they had done to their partners or children. I only slowly became aware of the complex set of tactics that men use to make violence against women invisible and to avoid taking responsibility for their actions. These tactics are listed below in the rough order that men employ them....

- Denial. - "I didn't hit her."

- Minimization. - "It was only a slap."

- Blame. - "She asked for it."

- Redefinition. - "It was mutual combat."

- Unintentionality. - "Things got out of hand."

- It's over now. - "I'll never do it again."

- It's only a few men. - "Most men wouldn't hurt a woman."

- Counterattack. - "She controls everything."

- Competing victimization. - "Everybody is against men [78]."

Kivel goes on to detail the ways these nine tactics are used to excuse (or deny) institutionalized racism. Each of these tactics also has its police analogy, both as applied to individual cases and in regard to the general issue of police brutality [79].

Here are a few examples:

(1) Denial.

- "The professionalism and restraint displayed by the police officers, supervisors, and commanders on the 'front line' ... was nothing short of outstanding [80]."

- "America does not have a human-rights problem [81]."

(2) Minimization.

- The injuries were "of a minor nature [82]."

- "Police use force infrequently [83]."

(3) Blame.

- "This guy isn't Mr. Innocent Citizen, either. Not by a long shot [84]."

- "They died because they were criminals [85]."

(4) Redefinition.

- It was "mutual combat [86]."

- "Resisting arrest [87]."

- "The use of force is necessary to protect yourself [88]."

(5) Unintentionality.

- "Officers have no choice but to use deadly force against an assailant who is deliberately trying to kill them.... [89]"

(6) It's over now.

- "We're making changes [90]."

- "We will change our training; we will do everything in our power to make sure it never happens again [91]."

(7) It's only a few men.

- "A small proportion of officers are disproportionately involved in use-of-force incidents [92]."

- "Even if we determine that the officers were out of line ... it is an aberration [93]."

(8) Counterattack.

- "The only thing they understand is physical force and pain [94]."

- "People make complaints to get out of trouble [95]."

(9) Competing victimization.

- The police are "in constant danger [96]."

- "[L]iberals are prejudiced against police, much as many white police are biased against Negroes [97]."

- The police are "the most downtrodden, oppressed, dislocated minority in America [98]."

Another commonly invoked rationale for justifying police violence is:

(10) The Hero Defense.

- "The police routinely do what the rest of us don't: They risk their lives to keep the peace. For that selfless bravery, they deserve glory, laud and honor [99]."

- "[Wlithout the police ... anarchy would be rife in this country, and the civilization now existing on this hemisphere would perish [100]."

- "[T]he police create a sense of community that makes social life possible [101]."

- "[T]hey alone stand guard at the upstairs door of Hell [102]."

This list is by no means exhaustive, but it should offer something of the tone that these excuses can take. Many of these approaches overlap, and often several are used in conjunction. For example, LAPD sergeant Stacey Koon offers this explanation for the beating of Rodney King:

From our view, and based on what he had already done, Rodney King was trying to assault an officer, maybe grab a gun. And when he was not moving, he seemed to be looking for an opportunity to hurt somebody, his eyes darting this way and that....

So we'd had to use force to make him respond to our commands, to make him lie still so we could neutralize this guy's threat to other people and himself.

The force we used was well within the guidelines of the Los Angeles Police Department; I'd made sure of that. And, I was proud of the professionalism [the officers had] shown in subduing a really monster guy, a felony evader seen committing numerous traffic violations [103].

In three paragraphs, Koon employs minimization, blame, redefinition, unintentionality, counterattacks, competing victimization, and the Hero Defense, As is usual, his little story stresses the possible danger of the situation, and elsewhere Koon emphasizes the generalizable sense of danger that officers experience: "[W]e'd all thought that maybe we were getting lured into something. It's happened before. How many times have you read about a cop getting killed after stopping somebody for a speeding violation [104]?"

The danger of the job is a constant theme in the defense of police violence. It is implicit (or sometimes explicit) in about half of the excuses listed above. By pointing to the dangers of the job, the excuse-makers don't only defend police actions in particular circumstances (which might actually have been dangerous) , but as often as not take the opportunity to mount a general defense of the police. This is a clever bit of sophistry, as cynical as a Memorial Day speech during wartime. It's one thing to make a banner of the bloody uniform when discussing a case where the cops actually were in danger, but quite another to do so when they might have been in danger, or only thought that they were.

The fact that policing is risky, by this view, seems to justify in advance whatever measures the police feel necessary to employ. This point lies at the center of the Hero Defense. Its genius is that it is so hard to answer. Few people are indifferent to the death of a police officer, espeCially when they feel (though only in some vague, patriotic kind of way) that it occurred because the officer was selflessly working - as former Philadelphia city solicitor Sheldon Albert put it - "so that you and I and our families and our children can walk on the streets [105]." The flaw of the Hero Defense, however, is both simple and (if you'll pardon the term) fatal: policing is not so dangerous as we are led to believe.

The Dangers of the Job

In 2001, 140 cops were murdered on the job. Most of these (71) were killed in the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. The remaining 69 deaths represent 65 separate incidents, most commonly domestic disturbances and traffic stops. Additionally, 77 officers died in on-duty accidents [106].

The 2001 figures are exceptional, skewed by the fact that more cops died in one day than in the entire rest of the year combined. Outside of the World Trade Center attack, only three officers were intentionally killed in the entire northeastern United States. If we bracket the anomaly of September 11, we get a more representative picture of the dangers police face: more officers died in accidents (77) than were murdered (69) [107]. This is not unusual. Between 1995 and 2000, 360 cops were murdered and 403 died in accidents. To take just one year's figures, 135 cops died in 2000; this number represents 51 murders and 84 accidents [108].

Naturally it is not to be lost sight of that these numbers represent human lives, not widgets or sacks of potatoes. But let's remember that there were 5,915 fatal work injuries in 2000 [109]. Policing may be dangerous, but it is not the most dangerous job available. In terms of total fatalities, more truck drivers are killed than any other kind of worker (852 in the year 2000) [110].

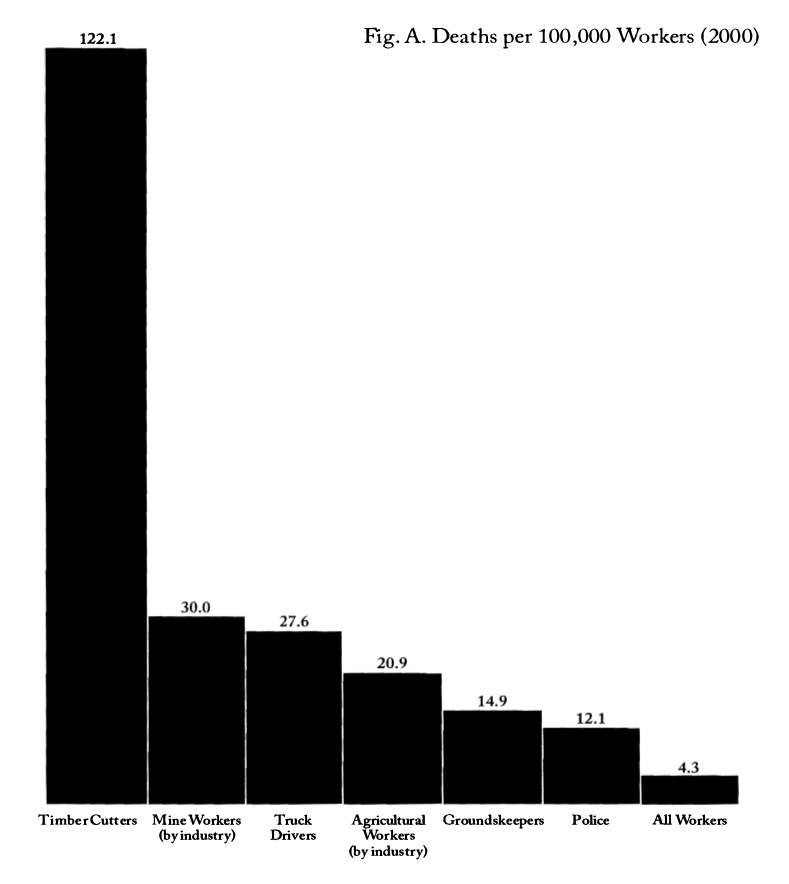

A better measure of occupational risk, however, is the rate of work-related deaths per 100,000 workers. In 2000, for example, it was 27.6 for truck drivers. At 12.1 deaths per 100,000, policing is slightly less dangerous than mowing lawns, cutting hedges, and running a wood-chipper: groundskeepers suffer 14.9 deaths per 100,000. By occupation, the highest rate of fatalities is among timber cutters, at 122.1 per 100,000 [111]. By industry, mining and farming are the most dangerous. "The mining industry recorded a rate of 30.0 fatal work injuries per 100,000 workers in 2000, the highest of any industry and about 7 times the rate for all workers. Agriculture recorded the second highest rate in 2000 (20.9 fatalities per 100,000 workers) [112]." The rate for all occupations, taken together, is 4.3 per 100,000 workers [113].

Where are the headlines, the memorials, the honor guards, and the sorrowful renderings of taps for these workers? Where are the mayoral speeches, the newspaper editorials, the sober reflections that these brave men and women died, and that others risk their lives daily, so that we might continue to enjoy the benefits of modern society?

Policing, it seems, is the only industry that both exaggerates and advertises its dangers. It has done so at a high cost, and to great advantage, though (as is so often the case) the costs are not borne by the same people who reap the benefits. The overblown image of police heroism, and the "obsession" with officer safety (Rodney Stark's term), do not only serve to justify police violence after the fact; by providing such justification, they legitimize violence, and thus make it more likely [114]. The exaggerated sense of danger has helped to re-order police priorities, to the detriment of the public interest.

Stark argues that

the police ought to understand clearly that they are being paid to take a certain degree of risk and that their safety does not come before public safety or the common good. Unfortunately, the police typically place their safety first and in recent years we have come to accept this priority [115].

By way of counterpoint, Stark describes the performance of the U.S. Marshals deployed to protect James Meredith during his September 1962 entrance into the University of Mississippi. Two hundred Marshals faced off with a crowd of 2,000 White people determined to prevent the school's integration. The Marshals stood for hours, while the crowd attacked them with bricks and sporadic sniper fire. Twenty-nine Marshals were injured, but they never broke ranks or fired their weapons. "Recalling this episode, consider how little we have come to expect of the police and how greatly we have come to share their obsession with their own safety [116]."

The police exaggerate the dangers they face, both in a general sense and in particular cases, where bloodied victims are charged with assault or resisting arrest, and the officer is left unharmed [117]. The fact is the police produce more casualties than they suffer. "Since 1976, an average of 79 police officers have been murdered each year in the line of duty.... [118]" All together, 1,820 law enforcement officers were murdered during the twenty-two-year period between 1976 and 1998 [119]. In the same time, the police killed 8,578 people, averaging 373 annually - more than one a day [120]. If we do the math, we see that the police kill almost five times as often as they are killed.

I will surely be accused of ghoulishly keeping score, of measuring the differences where I should be emphasizing the shared tragedy, of subtracting when I ought to be adding. It isn't my purpose here to disregard the deaths of the police, only to put them in perspective. The disparity between the violence police face and the violence they use is striking, especially if we remember that the available statistics reflect the officers' tendency to overstate the dangers they face and understate their own use of force, both in terms of degree and frequency. The fact that police use more force than they face is incontrovertible; it is left for us to wonder how often the police use violence - in some cases, deadly force - that is out of all proportion to the danger they face.

The available studies tell us very little about the prevalence of excessive force, but they do indicate that the police use violence more often, at higher levels, and with deadlier effects, than they actually encounter it [121]. This disparity should not be surprising, considering the nature of policing - the imperative to maintain control at all times, in every situation (hardly a realistic goal), the training to use escalating levels of force to gain compliance, and authority unhindered by genuine oversight. Policing, as I said earlier, is inherently violent; this violence, generally speaking, seems to be of an offensive - rather than defensive - character. In essence, the police are professional bullies. And like all bullies, the thing they most fear is an even fight. As Kenneth Bradley, a Miami-Dade Metro officer sees it: "I don't get paid to get hurt, and I don't get paid to fight fair.... [122]" No wonder, then, that the violence used by the police far outstrips anything used against them.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, "National Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries in 2000"

Institutionalized Brutality

Given such pervasive violence, it is astonishing that discussions of police brutality so frequently focus on the behavior of individual officers. Commonly called the "Rotten Apple" theory, the explanation of police misconduct favored by police commanders and their ideological allies holds that police abuse is exceptional, that the officers who misuse their power are a tiny minority, and that it is unfair to judge other cops (or the department as a whole) by the misbehavior of the few [123]. This is a handy tool for diverting attention away from the institution, its structure, practices, and social role, pushing the blame, instead, onto some few of its agents [124]. It is, in other words, a means of protecting the organization from scrutiny, and of avoiding change.

Despite the official insistence to the contrary, it is clear that police organizations, as well as individual officers, hold a large share of the responsibility for the prevalence of police brutality [125]. Police agencies are organizationally complex, and brutality may be promoted or accommodated within any (or all) of its various dimensions. Both formal and informal aspects of an organization can help create a climate in which unnecessary violence is tolerated, or even encouraged. Among the formal aspects contributing to violence are the organization's official policies, its identified priorities, the training it offers its personnel [126], its allocation of resources, and its system of promotions, awards, and other incentives [127]. When these aspects of an organization encourage violence - whether or not they do so intentionally, or even consciously - we can speak of brutality being promoted "from above." This understanding has been well applied to the regimes of certain openly thuggish leaders - Bull Connor, Richard Daley, Frank Rizzo [128], Daryl Gates, Rudolph Giuliani (to name just a few) - but it needn't be so overt to have the same effect.

On the other hand, when police culture and occupational norms support the use of unnecessary violence, we can describe brutality as being supported "from below." Such informal conditions are a bit harder to pin down, but they certainly have their consequences. We may count among their elements insularity [129], indifference to the problem of brutality [130], generalized suspicion [131], and the intense demand for personal respect [132]. One of the first sociologists to study the problem of police violence, William Westley, described these as "basic occupational values," more important than any other determinant of police behavior:

[The policeman] regards the public as his enemy, feels his occupation to be in conflict with the community and regards himself as a pariah. The experience and the feeling give rise to a collective emphasis on secrecy, an attempt to coerce respect from the public, and a belief that almost any means are legitimate in completing an important arrest. These are for the policeman basic occupational values. They arise from his experience, take precedence over his legal responsibilities, are central to an understanding of his conduct, and form the occupational contexts with which violence gains its meaning [133].

Police violence is very frequently over-determined-promoted from above and supported from below. But where it is not actually encouraged, sometimes even where individuals (officers or administrators) disapprove of it, excessive and illegal force are nevertheless nearly always condoned. Among police administrators there is the persistent and well-documented refusal to discipline violent officers; and among the cops themselves, there is the "code of silence."

In its 1998 report, Human Rights Watch noted the inaction of police commanders:

Most high-ranking police officials, whether at the level of commissioner, chief, superintendent, or direct superiors, seem uninterested in vigorously pursuing high standards for treatment of persons in custody. When reasonably high standards are set, superior officers are often unwilling to require that their subordinates consistently meet them [134].

Even where officers are found guilty of misconduct, discipline rarely follows. For example, in 1998 New York's Civilian Complaint Review Board issued 300 findings against officers; fewer than half of these resulted in disciplinary action [135].

LAPD assistant chief Jesse Brewer told the Christopher Commission:

We know who the bad guys are. Reputations become well known, especially to the sergeants and then of course to lieutenants and captains in the areas. But, I don't see anyone bringing these people up and saying, "Look, you are not conforming, you are not measuring up. You need to take a look at yourself and your conduct and the way you're treating people" and so forth. I don't see that occurring.... The sergeants don't, they're not held accountable so why should they be that much concerned[?]... I have a feeling that they don't think that much is going to happen to them anyway if they tried to take action and perhaps not even be supported by the lieutenant or the captain all the way up the line when they do take action against some individual [136].

Rank-and-file cops, likewise, are extremely reluctant to report the abuses they witness. Some of this reluctance, surely, is a reflection of their superiors' indifference. (After all, if nothing's going to come of it, why report it?) But their peers also enforce this silence. A National Institute of Justice study on police integrity discovered

a large gap between attitudes and behavior. That is, even though officers do not believe in protecting wrongdoers, they often do not turn them in. More than 80 percent of police surveyed reported that they do not accept the "code of silence" (i.e., keeping quiet in the face of misconduct by others) as an essential part of the mutual trust necessary to good policing.... However, about one-quarter (24.9 percent) of the sample agreed or strongly agreed that whistle blowing is not worth it, more than two thirds (67.4 percent) reported that police officers who report incidents of misconduct are likely to be given a "cold shoulder" by fellow officers, and a majority (52.4 percent) agreed or strongly agreed that it is not unusual for police officers to "turn a blind eye" to other officers' improper conduct.. . A surprising 6 in 10 (61 percent) indicated that police officers do not always report even serious criminal violations that involve the abuse of authority by fellow officers [137].

We should remember that these numbers reflect the reluctance of police to report misconduct when they recognize it as such. Given police attitudes about the use of force (when nearly a quarter of officers - 24.5 percent - think it acceptable to use illegal force against a suspect who assaults an officer) [138], we can reasonably conclude that the police report their colleagues' excessive force only in the rarest of circumstances.

I have, to this point, concentrated on the means by which violence (and excessive force in particular) is institutionalized by police agencies. That is, I have discussed the ways police organizations produce and sanction violence, even outside the bounds of their own rules and the law. This examination has provided a brief sketch of the way the institution shapes violence, but has not thus far considered the implications of this violence for the institution. It seems paradoxical that an institution responsible for enforcing the law would frequently rely on illegal practices. The police resolve this tension between nominally lawful ends and illegal means by substituting their own occupational and organizational norms for the legal duties assigned to them. Westley suggests:

This process then results in a transfer in property from the state to the colleague group. The means of violence which were originally a property of the state, in loan to its law-enforcement agent, the police, are in a psychological sense confiscated by the police, to be conceived of as a personal property to be used at their discretion [139].

From the officers' perspective, the center of authority is shifted and the relationship between the state and its agents is reversed. The police become a law unto themselves.

This account reflects the attitudes of the officers, and explains many of the institutional features already discussed. It also identifies an important principle of police ideology, one that (as we shall see in later chapters) has guided the development of the institution, especially in the last half-century. But Westley's theory also raises some important questions. Chief among these: why would the state allow such a coup?

The Police, The State, and Social Conflict

We might also ask: To what degree is violence the "property" of the state to begin with? At what point does the police co-optation of violence challenge the state's monopoly on it? When do the police, in themselves, become a genuine rival of the state? Are they a rival to be used (as in a system of indirect rule) or a rival to be suppressed? Is there a genuine danger of the police becoming the dominant force in society, displacing the civilian authorities? Is this a problem for the ruling class? Might such a development, under certain conditions, be to their favor? These are good questions, and we will get to them.

heir favor? These are good questions, and we will get to them. For now, let us concentrate on the question of why the state (meaning, here, the civil authorities) would let the police claim the means of violence as their own. Police brutality does not just happen; it is allowed to happen. It is tolerated by the police themselves, those on the street and those in command. It is tolerated by prosecutors, who seldom bring charges against violent cops, and by juries, who rarely convict. It is tolerated by the civil authorities, the mayors, and the city councils, who do not use their influence to challenge police abuses. But why?

The answer is simple: police brutality is tolerated because it is what people with power want.

This surely sounds conspiratorial, as though orders issued from a smoke filled room are circulated at roll call to the various beat cops and result in a certain number of arrests and a certain number of gratuitous beatings on a given evening. But this isn't what I mean, or not quite. Instead, the apparent conflict between the law and police practices may not be so important as we tend to assume. The two may, at times, be at odds, but this is of little concern so long as the interests they serve are essentially the same. The police may violate the law, as long as they do so in the pursuit of ends that people with power generally endorse, and from which such people profit. This idea may become clearer if we consider police brutality and other illegal tactics in relation to lawful policing: when the police enforce the law, they do so unevenly, in ways that give disproportionate attention to the activities of poor people, people of color, and others near the bottom of the social pyramid [140]. And when the police violate the law, these same people are their most frequent victims. This is a coincidence too large to overlook. If we put aside, for the moment, all questions of legality, it must become quite clear that the object of police attention, and the target of police violence, is overwhelmingly that portion of the population that lacks real power. And this is precisely the point: police activities, legal or illegal, violent or nonviolent, tend to keep the people who currently stand at the bottom of the social hierarchy in their "place," where they "belong" - at the bottom. This is why James Baldwin said that policing was "oppressive" and "an insult."

Put differently, we might say that the police act to defend the interests and standing of those with power - those at the top. So long as they serve in this role, they are likely to be given a free hand in pursuing these ends and a great deal of leeway in pursuing other ends that they identify for themselves . The laws may say otherwise, but laws can be ignored.

In theory, police authority is restricted by state and federal law, as well as by the policies of individual departments. In reality, the police often exceed the bounds of their lawful authority, and rarely pay any price for doing so. The rules are only as good as their enforcement, and they are seldom enforced. The real limits to police power are established not by statutes and regulations - since no rule is self-enforcing - but by their leadership and, indirectly, by the balance of power in society.

So long as the police defend the status quo, so long as their actions promote the stability of the existing system, their misbehavior is likely to be overlooked. It is when their excesses threaten this stability that they begin to face meaningful restraints. Laws and policies can be ignored and still provide a cover of plausible deniability for those in authority. But when misconduct reaches such a level as to prove embarrassing, or so as to provoke unrest, the authorities may have to tighten the reins - for a while[141]. Token prosecutions, minimal reforms, and other half-measures may give the appearance of change, and may even serve as some check against the worst abuses of authority, but they carefully fail to affect the underlying causes of brutality. It would be wrong to conclude that the police never change. But it is important to notice the limits of these changes, to understand the influences that direct them, and to recognize the interests that they serve. Police brutality is pervasive, systemic, and inherent to the institution. It is also, as we shall see, anything but new.