- Return to book

- Review this book

- About the author

- Publishing Info

- 1. Contents

- 2. Acknowledgments

- 3. Introduction by Joy James

- 4. Author's Preface, 2007

- 5. Foreword: Police and Power in America

- 6. One: Police Brutality in Theory and Practice

- 7. Two: The Origins of American Policing

- 8. Three: The Genesis of a Policed Society

- 9. Four: Cops and Klan, Hand in Hand

- 10. Five: The Natural Enemy of the Working Class

- 11. Six: Police Autonomy and Blue Power

- 12. Seven: Secret Police, Red Squads, and the Strategy of Permanent Repression

- 13. Eight: Riot Police or Police Riots?

- 14. Nine: Our Friendly Neighborhood Police State

- 15. Afterword: Making Police Obsolete

- 16. Notes

- 17. Selected Bibliography

- 18. Index

- 19. About the Author

2

The Origins of American Policing

In February 1826, Aziel Conklin, the captain of the watch in New York's third district, was suspended - but later reinstated - after a conviction for assault and battery [1]. This incident was not especially unusual at the time. Even now, it would only stand out because cops are so rarely convicted, regardless of the evidence against them. Yet if the licensed use of violence is not new, the system employing it today looks very different than that of the 1820s. And if the abuse of authority is itself a constant feature of government, the nature of that authority has undergone substantial changes.

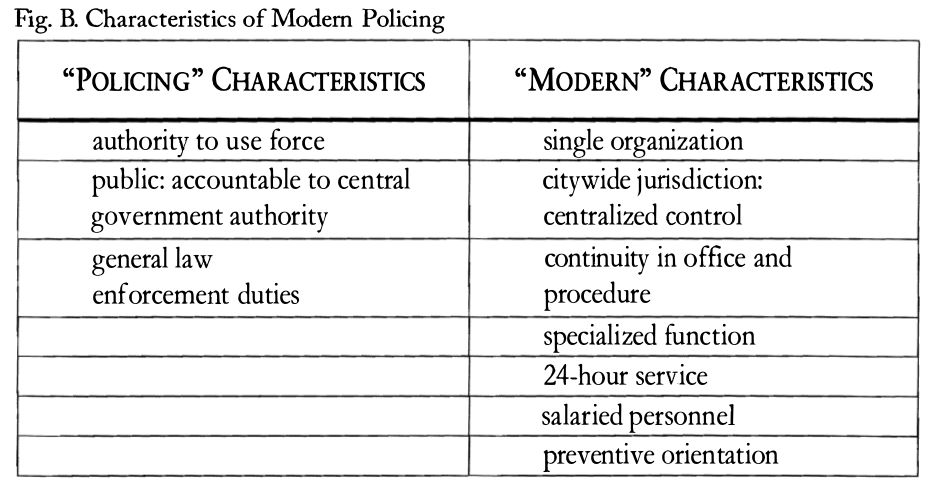

Characteristics of Modern Police

Policing itself is not a distinctly modern activity [2]. It has existed in some form, under numerous political systems, in disparate locations, for centuries. Yet most of the institutions historically responsible for law enforcement would not be recognizable to us as police. Colonial America, for example, had nothing like our modern police departments.

The earliest specialized police were watchmen.... However, although their function was certainly specialized, it is not always clear that it was policing. Very often they acted only as sentinels, responsible for sum moning others to apprehend criminals, repel attack, or put out fires [3].

It was not until the middle of the nineteenth century that most American cities had police organizations with roughly the same form and function as our contemporary departments.

Though most historians agree it was in the mid-1800s that police forces throughout the United States converged into a single type, it has been surprisingly difficult to enumerate the major features of a modern police operation. David Bayley defines the modern police in terms of their public auspices, specialized function, and professionalism [4], though he does also mention their non-military character [5] and their authority to use force [6]." Richard Lundman offers four criteria: full-time service, continuity in office, continuity in procedure, and control by a central governmental authority [7]. Selden Bacon, meanwhile. suggests six characteristics:

(a) citywide jurisdiction.

(b) twenty-four-hour responsibility,

(c) a single organization responsible for the greater part of formal enforcement,

(d) paid personnel on a salary basis,

(e) a personnel occupied solely with police duties,

(f) general rather than specific functions [8].

Raymond Fosdick argues that the defining mark of modern police departments is their organization under a single commander [9]. And Eric Monkkonen takes as his sole requirement the presence of uniforms [10].

Three of these criteria are easily done away with. The use of uniforms is neither a necessary nor a unique feature of modern policing. Some police officers, especially detectives, do not wear uniforms, and are no less modern for that fact. Furthermore, even within the history of law enforcement, uniforms predate the modern institution. The London Watch, for example, was uniformed in 1791 [11]. Likewise, though most police agencies are headed by a single police chief, this is not always the case, and has not always been the case, even in departments that are distinctly modern. Police boards of various kinds have moved in and out of fashion throughout the modern period, especially at the cusp of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The civilian character of the police is more problematic, and, precisely because it is problematic I will put it aside as a suggested criterion for modern police. The relationship between policing and the military has always been complex and controversial, and if current trends are any indication, it will remain so for some time. Given the ambiguous and shifting character of the police, it seems unwise to generalize about its essentially civilian (or military) nature, and I do not wish to define away the problem at the expense of a more nuanced analysis [12].

Those characteristics remaining may be divided into two groups. The first are the defining characteristics of police:

- the authority to use force,

- a public character and accountability (at least in principle) to some central governmental authority, and

- general law enforcement duties (as opposed to limited, specified duties such as parking enforcement or animal control).

These traits, I think, are essential to any organization that claims to be engaged in policing.

The second set comprises those criteria distinguishing modern policing from earlier forms. These include:

- the investment of responsibility for law enforcement in a single organization,

- citywide jurisdiction and centralization

- an intended continuity in office and procedure [13],

- a specialized policing function (meaning that the organization is only or mainly responsible for policing, not for keeping the streets clean, putting out fires, or other extraneous duties),

- twenty-four-hour service, and

- personnel paid on a salary basis rather than by fee.

There is one final characteristic that deserves consideration. The development of policing has been guided in large part by an emerging orientation toward preventive rather than responsive activity. Though this idea was firmly established by the time modern departments took the stage, it was not until quite some time later that specific techniques of prevention entered into use, and the degree to which the police do, or can, or should, act to prevent crime remains even now a matter of intense debate.

Rather than use these factors to draw a sharp line demarcating a clearly identifiable set of modern police (a line most police departments will have crossed and re-crossed), I propose we use these criteria to place various organizations on a continuum as being more or less modern depending on the degree to which they display these characteristics [14]. (I have listed the traits here in order of what I take to be their relative significance.) This approach may seem a bit impressionistic, but I think the picture it offers is helpful in understanding the evolution of police systems. For the most part, the creators of the new police did not see themselves as marching inexorably toward an ideal of modern policing. Instead, they adapted preexisting institutions to the demands of new circumstances, evolving their systems slowly through a process of invention and imitation, improvisation and experimentation, promise and compromise, trial and error. The rate of progress was unsteady, its path wavering, its advances frequently reversed, and its direction determined by a variety of factors including political pressure, scandals, wars, riots, economics, immigration, budget constraints, the law, and sometimes crime.

There is a further advantage to this approach: it acknowledges the fact of continuing development and leaves open the possibility of further modernization. Hence, rather than a revolution of modernity, occurring between 1829 and about 1860, we are faced with a much more protracted process. We find police departments approaching their modern form quite a while earlier; and yet, we can recognize that these same departments may not be fully modernized, even now [15]. In short, this view avoids the tendency to treat our contemporary institution as the final product of earlier progress, as an end-point marking completion, and instead situates it as one stage in an ongoing process.

English Predecessors

Many people find it astonishing that the police have predecessors. They seem to imagine that the cop has always been there, in something like his present capacity, subject only to the periodic change of uniform or the occasional technological advance. Quite to the contrary, the police have a rich and complex history, if an ugly one. Our contemporary institution owes much of its character to those that came before it, including those offices imported or imposed during the colonial period. These in turn have their own stories, closely linked to the creation of modern states. It is worth considering this lineage and the forces that propelled change, from one form of control to another.

During the time between the fall of Rome and the rise of modern states, policing - like political authority - became quite decentralized. "Gradually, new superordinate kingdoms were formed, delegating the power to create police but holding on to the power to make law [16]". Within such arrangements, policing initially took an informal mode, such as that of the frankpledge system in England [17]. Under this system, families grouped themselves together in sets of ten (called "tythings") and collections of ten tythings (called "hundreds"). The heads of these families pledged to one another to obey the law. Together they were responsible for enforcing that pledge, apprehending any of their own who violated it, and combining for mutual protection. If they failed in these duties, they were fined by the sovereign [18].

Under the frankpledge system, the responsibility for enforcing the law and maintaining order fell to everyone in the community.

Our extremely modern concept of a specialized police force did not then exist. Neither was there any public means for repressing or preventing crime, as distinguished from its detection and the apprehension of offenders. The members of each tything were simply bound to a mutual undertaking to apprehend, and present for trial, any of their number who might commit an offense [19].

This arrangement relied on the social conditions present in small communities, especially the sense of interpersonal connection and interdependence. But we should be careful of romanticizing this idyllic scenario. The frankpledge system was imposed by the Norman conquerors as a means of maintaining colonial rule. Essentially, they forced the conquered communities to enforce the Norman law [20].

Still, the system was rather limited in its authoritarian uses, as it depended on a common acceptance of the law. Hence, English sovereigns later found it necessary to supplement the frankpledge with the appointment of a shire reeve, or sheriff, to act in local affairs as a general representative of the crown. The sheriff was responsible for enforcing the monarch's will in military, fiscal, and judicial matters, and for maintaining the domestic peace [21]. Sheriffs were appointed by and directly accountable to the sovereign. They were responsible for organizing the tythings and the hundreds, inspecting their weapons, and, when necessary, calling together a group of men to serve as a posse comitatus, pursuing and apprehending fugitives. The sheriffs were paid a portion of the taxes they collected, which led to abuses and made them rather unpopular figures [22]. Eventually, following a series of scandals and complaints, the sheriff's powers were eroded and some of his responsibilities were assigned to new offices, including the coroner, the justice of the peace, and the constable [23].

According to the 1285 Statute of Winchester, the constable was responsible for acting as the sheriff's agent. Two constables were appointed for every hundred, thus providing more immediate supervision of the tythings and hundreds [24].

[The constable's] early history is closely intertwined with military affairs and with martial law; for after the Conquest the Norman marshals, predecessors of the modern constable, held positions of great dignity and were drawn for the most part from the baronage. As leaders of the king's army they seem to have exercised a certain jurisdiction over military offenders, particularly when the army was engaged on foreign soil, and therefore beyond the reach of the usual institutions of justice. The disturbed conditions attending the Wars of the Roses brought the constables further powers of summary justice, as in cases of treason and similar state crimes. They therefore came to be a convenient means by which the English kings from time to time overrode the ordinary safeguards of English law. These special powers, originating in the "law marshal," were expanded until they came to represent what we know as "martial law [25]."

Beyond his original military function, and the additional job of serving the sheriff, the constable was also responsible for a host of other duties, including the collection of taxes, the inspection of highways, and serving as the local magistrate. Ironically, as the posse comitatus came increasingly to act as a militia, the constable was without assistance in policing [26]. By the end of the thirteenth century, the constable was no longer connected to the tything; he acted instead as an agent of the manor and the crown [27]. By the beginning of the sixteenth century, the constable's function was quite limited; constables only made arrests in cases where the justice of the peace issued a warrant [28].

Around the middle of the thirteenth century, towns of notable size were directed by royal edict to institute a night watch [29]. This was usually an unpaid, compulsory service borne by every adult male. Carrying only a staff and lantern, the watch would walk the streets from late evening until dawn, keeping an eye out for fire, crime, or other threats, sounding an alarm in the event of emergency. "Charlies" - so called because they were created during the reign of Charles II [30] - were unarmed, untrained, under-supervised, often unwilling, and frequently drunk.

In 1727, Joseph Cotton, the Deputy Steward of Westminster, visited St Margaret's Watchhouse and complained that there was "neither Constable, Beadle, Watchman, or other person (save one who was so Drunk that he was not capable of giving any Answer) Present in, or near the said Watchhouse." A few years later, in 1735, John Goland of Bond Street complained to the Burgesses that he had been robbed three times in five years, noting that he "generally finds the Watchmen drunk, and wandering about with lewd Women. .. [31]"

The watch thus represented neither a significant bulwark against crime nor a major source of power for the state. Yet the watch continued in various forms for 600 years.

During the eighteenth century, the London Watch underwent a long series of reforms [32]. While neglect of duty and drunkenness remained major complaints, most of the characteristics of modern police were introduced to the watch in this period, first in one locale and then in the others. "The goal was a system of street policing that was honest, accountable, and impartial in its administration and operation.... [33]" Toward this end, the West End parishes of St James, Piccadilly, and Saint George, Hanover Square began paying watchmen in 1735; most other parishes adopted the practice within the next: fifty years [34]. During this same time, more men were hired, hours of operation were expanded, command hierarchies and plans of supervision were drafted, minimum qualifications established, record-keeping introduced, and pensions offered [35].

By 1775, Westminster and several neighboring parishes had a night watch system that was both professional and hierarchical in structure, charged with preventing crime and apprehending night walkers and vagabonds. While police authority did remain divided between several local bodies and officials, decentralization was not necessarily synonymous with defectiveness. These parochial authorities put increasing numbers of constables, beadles [church officials], watch men, and [militia] patrols on the street, paid and equipped them. They spent increased amounts of time disciplining them when they were delinquent and increasing amounts of money on wages [36].

Thus, during the eighteenth century the London Watch came very nearly to resemble the modern police department that replaced it.

The watch was also supplemented by various private efforts, including a "river police" created by local merchants and taken over by the government in 1800 [37]. "By 1829 London had become a patchwork of public and private police forces .. supported by vestries, church wardens, boards of trustees, commissioners, parishes, magistrates, and courts-leet [38]." Among this mix, we find one group worthy of special notice - the thieftakers, forerunners of the modern detective. Despite their name, thieftakers were less interested in catching thieves than in retrieving stolen property and collecting rewards. And the easiest way to do that was to act as a fence for the thieves, returning the goods and splitting the fee. Until his execution in 1725, Jonathan Wild was England's most prominent thieftaker, controlling an international operation that included warehouses in two countries and a ship for transport [39].

Such was the state of policing when Robert Peel, the home secretary, proposed a plan for a citywide police force. This body, the Metropolitan Police Department - now nicknamed "Bobbies" after their creator, but commonly called "crushers" by the public of the time [40] - adopted many of the innovations previously introduced in the local watch, adding to these a new element of centralization [41]. It thus fulfilled most of the criteria defining modern policing.

Peel based this effort on his experiences in Ireland, where he had introduced the Royal Irish Constabulary in 1818 [42]. Hence both the traditional watch and the police system that came to replace it were informed by the experience of colonial rule. They were each created by foreign conquerors to control rebellious populations. Peel had seen the difficulties of military occupation and understood the need to establish some sort of legitimacy. He crafted his police accordingly - first in Ireland, and then, with revisions, in England [43]. In London the police uniforms and equipment were selected with an eye toward avoiding a military appearance, though critics of the police idea still drew such comparisons [44].

In 1829, citing a rise in crime (especially property crime), Parliament accepted Peel's proposal with only a few adjustments [45]. The most important of these compromises excluded the old City of London from the jurisdiction of the Metropolitan Police. The old City of London (about one square mile, geographically) retained its own police force, which in 1839 was reorganized on the Metropolitan model [46]. Meanwhile, the watch and river police were preserved and proved for some time more effective than the new Metropolitans [47]. Still, though they lacked citywide jurisdiction and sole policing authority, the London Metropolitan Police are generally credited as the first modern police department.

Some historians treat the modern American police as a straightforward application of Peel's model. As we shall see, however, policing in the United States followed a separate course, motivated by different concerns and producing unique institutional arrangements. In fact, I shall argue that American policing systems, especially those designed for slave control, neared the modern type well before Peel's reforms.

Colonial Forerunners

The American colonies mostly imported the British system of sheriffs, constables, and watches, though with some important differences.

Sheriffs at first were appointed by governors, and made responsible for apprehending suspects, guarding prisoners, executing civil processes, overseeing elections, collecting taxes, and performing various fiscal functions [48]. Corruption in all of these duties was quite common, with sheriffs accepting bribes from suspects and prisoners, neglecting their civil duties, tampering with elections, and embezzling public funds [49]. The sheriff was empowered to make arrests when issued a warrant, or without one in certain circumstances, and was given additional duties during emergencies, but during the colonial period the office was only tangentially concerned with criminal law [50].

The constable's duties were similarly varied. He was charged with summoning citizens to town meetings, collecting taxes, settling claims against the town, preparing elections, impressing workers for road repair, serving warrants, summoning juries, delivering fugitives to other jurisdictions, and overseeing the night watch. In addition, he was, in theory, expected to enforce all laws and maintain the Crown's peace [51]. In practice, however, constables were paid by a system of fees, and tended to concentrate on the better-paying tasks [52].

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, both the sheriff and the constable were elected positions [53]. Still, they were not popular jobs; many people refused to serve when elected [54], and the authority of each office was commonly challenged, sometimes by violence. In 1756, for example, Sheriff John Christie was killed when trying to make an arrest. James Wilkes was convicted, but was soon pardoned by Governor Sir Charles Hardy, who reasoned that Wilkes

had imbibed and strongly believed a common Error generally prevailing among the Lower Class of Mankind in this part of the world that after warning the Officer to desist and bidding him to stand off at his Peril, it was lawful to oppose him by any means to prevent the arrest [55].

The fact that such a view would be respected, despite its legal inaccuracy, says a great deal about the weakness of the sheriff's position [56].

Neither of these offices was designed for what we now consider police work, and neither ever fully adapted itself to that function [57]. Constables survived into the twentieth century, though only as a kind of rural relic [58]. Sheriffs, meanwhile, retained many of their original duties - especially those concerning jails - and in some places still patrol the unincorporated areas of counties, though even in this respect state police forces sometimes supersede them.

Rather than invest much authority in these offices, the colonial government relied primarily on informal means of policing. As public nuisances arose concerning the behavior of slaves, the delivery of goods, sanitation, street use, gambling, and the like, the local government responded by instituting regulations. These would generally be ignored. To remedy this deficiency, the civil authorities called on the family and church to use their influence to bring about compliance. Where that failed, they would institute a system of fines (for violators) and rewards (for informers). They might then direct the constable to enforce the laws, or else appoint special informers concerned only with that particular law. Eventually towns began consolidating these positions and appointing general officers called marshals [59].

Citizens were further expected to participate in law enforcement through the night watch.

The character of the nightwatch varied from time to time. Sometimes it was composed entirely of civilians forced to take their regular turn as watchmen or pay for a substitute to replace them. At other times, especially during the intercolonial wars, the militia took over the watch. At still other times, a paid constable's watch was used, or citizens them selves were paid to guard the city [60].

As in England , the watch was charged with keeping order, reporting fires, sounding an alarm when crimes were discovered, detaining suspicious persons, and sometimes suppressing riots and lighting street lamps [61].

The Boston Watch was in many respects typical. All men over 18 years old were required to serve in person or provide a substitute (though ministers and certain public officials were exempted from duty) . The state legislature ordered the watchmen to "see that all disturbances and disorders in the night shall be prevented and suppressed" and gave them the

authority to examine all persons, whom they have reason to suspect of any unlawful design, and to demand of them their business abroad at such time, and whither they are going; to enter any house of ill-fame for the purpose of suppressing any riot or disturbance [62].

They were further instructed to

walk in rounds in and about the streets, wharves, lanes, and principal inhabited parts, within each town, to prevent any danger by fire, and to see that good order is kept, taking particular observation and inspection of all houses and families of evil fame [63].

New York provided similar instruction in 1698. The watchmen were told to go

round the Citty Each Hour in the Night with a Bell and there to proclaime the season of the weather and the Hour of the night and if they Meet in their Rounds Any people disturbing the peace or lurking about Any persons house or committing any theft they take the most prudent way they Can to Secure the said persons [64].

Like the modern police, the colonial watch was public in character and accountable to a central authority, usually either a town council or state legislature. Unlike the modern police, however, the watch had only limited authority to use force, with no training and usually no equipment for doing so. As far as "modern" characteristics go, the watch shared responsibility for enforcement with the constables, sheriffs, and sometimes other inspectors. Thus it was not the major body responsible for law enforcement. Its personnel rotated with deliberate frequency, and many places it only patrolled part of the year. Hence, it lacked continuity in office and procedure. While the watch was concerned with crime, it was often more concerned with other dangers, especially fire and military attack; thus it lacked the specialized policing function. Except in times of emergency, the watch only patrolled at night (offering no twenty-four-hour service). And for the most part, its personnel were not paid at all. In sum, by our criteria, the colonial watch may be counted as a policing effort, but in no way did it constitute a modern police agency.

The standard story in the history of policing, if we may speak of such a thing, presents the modern American police force as a direct adaptation of the night watch, following the English pattern [65]. But this story leaves out significant stages in the development of American policing. Or, put differently, it omits an entire branch of the American police family tree.

In fact, the first major reform of the traditional system did not occur in any of the big northwestern cities in the mid-1800s but in the cities of the Deep South in a much earlier period . As early as the 1780s Charleston introduced a paramilitary municipal police force primarily to control the city's large population of slaves. In later years, Savannah, New Orleans, and Mobile did the same [66].

These police forces, which I will refer to as City Guards, were distinct from both the militia and the watch . They were armed, uniformed, and salaried; they patrolled at night but kept a reserve force for daytime emergencies. In most respects, they resembled modern American police departments to the same degree as did the London Metropolitan Police of 1829.

Of course, these City Guards did not arise out of nothing. To understand their origin, we should consider the peculiar institutions of Southern society, its social and economic systems and the police measures that arose to preserve them.

Slave Patrols

Relying on a slave economy, the American South faced unique problems of social control, especially in areas where White people were in the minority. Regardless of their own economic class or ethnic background, White people were haunted by the prospect of a slave revolt They became utterly obsessed with controlling the lives of Black people, free and slave, and developed a deep and terrible fear of any unsupervised activity in which Black people might engageY As a result, the South developed distinctive policing practices. Called "slave patrols," "alarm men," or "searchers," by the authorities who appointed them, they were known as "paddyrollers," "padaroles," "padaroes," and "patterolers" by the populations they policed [68].

Michael Hindus cites three related reasons why the criminal justice system in the South developed along different lines than it did in the North: 1) tradition, 2) social and economic development, and 3) slavery [69]. Of these three, slavery exerted the most powerful influence. It held a central place in Southern society, in the social and political as well as the economic life of the region. For many Southerners, a future without slavery was literally inconceivable [70]. Thus the whole of Southern society was, at times, directed to the defense of the "peculiar institution." Where the demands of slavery conflicted with the region's traditions and social development - and to a lesser extent when it interfered with economic development - the maintenance of the slave system was nearly always preferred [71].

Faced with the difficulties of keeping a major portion of the population enslaved to a small elite, Southern society borrowed from the practices of the Caribbean, especially Barbados. There, slave owners used professional slave catchers and militias to capture runaways, while overseers were responsible for maintaining order on the plantations. The weaknesses of this system led to the creation of slave codes, laws directed specifically to the governing of slaves. Beginning in 1661, the slave code shifted the responsibilities of enforcement from the overseers to the entire White population. Shortly thereafter, in the 1680s, the militia began making regular patrols to catch runaways, prevent slave gatherings, search slave quarters, keep order at markets, funerals, and festivals, and generally intimidate the Black population [72].

The final move in policing Barbadian slaves in the seventeenth century came with the importation of two thousand professional English soldiers, who were installed on plantations as intimidating "militia tenants." Arriving between 1696 and 1702, they did not perform manual labor but instead functioned exclusively as slave control forces. Their presence served the White colonists' purposes well: throughout the eighteenth century only one slave rebellion attempt was reported in Barbados [73].

During the same period, South Carolina passed laws restricting the slaves' ability to travel and trade, and created the Charleston Town Watch. Beginning in 1671, this watch consisted of the regular constables and a rotation of six citizens. It looked for any sign of trouble-fires, Indian attacks, or slave gatherings. The laws also established a militia system, with every White man between sixteen and sixty years old required to serve [74].

In 1686, South Carolina passed a law enabling any White person to apprehend and punish runaway slaves." A few years later, the 1690 Act for the Better Ordering of Slaves required "all persons under penalty of forty shillings to arrest and chastise any slave out of his home plantation without a proper pass [76]." Those who captured runaways would receive a reward [77].

In 1704, fears of a Spanish invasion, combined with the ever-present threat of a slave revolt, led South Carolina to form its first official slave patrols. The colony faced two types of danger and divided its military capacity accordingly. Henceforth, the militia would guard against outside attack, and the patrol would be left behind to protect against insurrection [78].

Patrollers would gather from time to time and, as instructed by the law,

ride from plantation to plantation, and into any plantation, within the limits or precincts, as the General shall think fitt, and take up all slaves which they shall meet without their master's plantation which have not a permit or ticket from their masters, and the same punish [79].

In 1721, the law was revised to shift its focus from runaways to revolts. The new law ordered the patrols to "prevent all caballings amongst negros, by dispersing of them when drumming or playing, and to search all negro houses for arms or other offensive weapons [80]." The patrollers seized other goods as well, alleging them to be stolen, and were permitted to keep for their own whatever they took [81].

The patrol was essentially an institutionalized extension of the more informal system described by the 1686 law. The law's intention was, foremost, to divide the means of protecting the city so that both internal and external threats could be met simultaneously. It did not represent an effort to specialize slave control, or to reduce the obligations of each White citizen, or to interfere with the personal authority of the slave owner. But whatever the intention behind it, the law did, or threatened to do, all three.

Reform required increasing the amount of time each man devoted to protecting the safety and property of others, which was repugnant to Southern White ideas of individual freedom and, indirectly, their sense of personal honor. No White man should have to cower before slaves, it was thought, and patrols were an unequivocal manifestation of White fear. Southern honor required the individual to protect his name and family without the assistance of courts or the community; patrols, by their very nature, were communal, intrusive in the master-slave relationship, and implied that the individual alone could not adequately control his bondsmen [82].

Slave patrols were both a product of White racism, vital to the survival of slavery, and a manifest contradiction of the ideology and culture it was meant to protect. 'To admit that danger existed was to concede the possibility of fear; to admit that slaves posed a threat could undermine confidence in an entire way of life [83]." Of course, to ignore the threat of insurrection could prove equally as dangerous. The patrols were created to defend slavery, but their effectiveness was limited by the same ideology that justified the slave system.

For White people in the South, slavery was valued, in part, as a means of maintaining the entire social order and a deeply cherished way of life. It would not be an exaggeration to say that they imagined that the slave system upheld civilization itself, in part by controlling the group that most threatened it - the slaves. This racist ideology was self-reinforcing, and provided for its own defense.

As long as Charlestonians believed that blacks were the sole threat to order, White supremacy served in lieu of a police force. In such a racially stratified society, with few legal rights accorded to the black man, every White person, by virtue of his skin, had sufficient authority over blacks [84].

So, rather than develop more formal means of control, Southern ideology encouraged a reliance on informal systems rooted in racism. This was not only true of the police function, but of all authority. While the rest of the country developed systems of authority that were formal, legalistic, and centered on the state, the South maintained a unique commitment to a system that was informal, personalistic (characterized by deference and paternalism), diffused, and in which the slate was kept deliberately weak. When compared to Northern cities of the nineteenth century, plantation life seems positively feudal. "In other words, the plantation was a sort of governmental unit as to the police control of the slave, and to its head, the slaveowner, was given in large measure the sovereign management of its affairs under certain restrictions [85]." The arrangement was, in the fullest, traditional sense of the word, patriarchal; not only slaves, but also White women and children were subject to the personal authority of male heads of households [86]. Any intercession in these relationships was apt to be viewed negatively. Slaveowners felt that any outside intervention - especially that of the state - represented not only a usurpation of their authority but also a personal slight, implying that the master was not up to the task of controlling his slaves [87].

This sentiment, an important aspect of Southern "honor," created a major impediment to the effective control of the Black population. It discouraged White elites from enhancing the means of social control.

[O]nly the state (through the agency of the courts, councils, and militia) could force whites to act in concerted fashion to protect their own self-interest. And some state legislatures, like South Carolina's, simply refused to reform patrol practices in order to coerce more public service from their constituents [88].

Progress, here, came not as the result o f continual efforts at critique and improvement, but in a rush during times of crisis, typically following real or rumored revolts. Aside from minor alterations in 1737 and 1740, the patrol system established in 1704 survived, virtually unaltered, until 1819. The 1737 and 1740 acts limited the personnel of the patrols, first to landowners of 50 acres or more, and then to slaveowners and overseers [89]. But in 1819, the state legislature - spurred by two separate slave revolts shortly before - again made all "free white males" aged 18 to 45 liable for patrol duty, without compensation. Substitutes could be sent, for a fee, and discipline came in the form of fines [90]. After this revision, the structure and activities of the patrols remained relatively unchanged until the Civil War [91].

While "[the patrol system in] South Carolina seems to have been the oldest, most elaborate, and best documented," other colonies followed suit [92]. Georgia, Tennessee, Kentucky, and Mississippi all had similar arrangements, with variations. In Georgia, slave patrols were also responsible for disciplining disorderly White people, especially vagrants [93]. In Tennessee, the law required slaveowners to provide patrols on the plantations themselves, in addition to those that rode between plantations. In Kentucky, after a series of revolts, some cities established round-the-clock patrols. And in Mississippi, the first patrols were federal troops; these were gradually replaced by the militia, and then by groups appointed by county boards [94].

Until 1660, Virginia relied more on indentured European servants than on African slaves, though both groups sought to escape their bonds. Initially, the colonists used the hue and cry to mobilize the community and recapture runaways. In 1669, the colonial legislature began offering a reward (paid in tobacco) to anyone who returned a runaway. And in 1680, as the slave population grew, slaves were required to carry passes, as debtors and Native Americans already had been. Slaves were singled out for special enforcement measures beginning in 1691, when the legislature required sheriffs to raise posses for their recapture. In 1727, this responsibility was transferred to the militia, creating the colony's first slave patrol. At first the militia only patrolled as needed, but after a failed rebellion in 1730, it began regular patrols two or three times each week. In 1754, county courts began paying patrollers and requiring reports from their captains. After that point, Virginia's patrols remained essentially the same until the Civil War [95].

North Carolina's system developed along similar lines, driven by the same concerns. The colony required passes for slaves, debtors, and Native Americans beginning in 1669. In 1753, patrols were instituted. Called "searchers," the patrols were initially responsible for searching the slaves' homes, but couldn't stop them between plantations. This function reflected the motives behind their creation: the lawmakers were more afraid of revolts than escapes. In 1779, paid patrols were established, with expanded powers for searching the homes of White people and stopping slaves whenever they were off the plantation [96]. With this they came to closely resemble the patrols already in place elsewhere, and after 1802 they were placed under the auspices of the county court, rather than the militia [97].

Whether supervised by the militia or the courts, whether chiefly concerned with escapes or revolts, whether paid or conscripted, whether slave-owners or poor White people, the rural patrols all engaged in roughly the same activities and served the same function. 'Throughout all of the [Southern] states during the antebellum period, roving armed police patrols scoured the countryside day and night, intimidating, terrorizing, and brutalizing slaves into submission and meekness [98]." They patrolled together in "beat companies," on horseback and usually at night [99]. Along the roads they would stop any Black person they encountered, demand his pass, beat him if he was without one, and return him to the plantation or hold him in the jail. For this, they carried guns, whips, and binding ropes [100].

They would search slaves' homes, and sometimes the homes of disreputable White people, looking for illegal visitors, weapons, and stolen goods. Guns and horses were confiscated as a matter of course, as were linen and china [101]; slaves weren't allowed to have anything too valuable. Books and paper were often confiscated as well; education itself was deemed subversive [102].

The patrols would break up any unsupervised gathering of slaves, especially meetings of religious groups the patrollers themselves disliked. Baptist and Methodist services were specifically targeted [103]. One former slave, Ida Henry, recalled an assault against her mother:

De patrollers wouldn't allow de slaves to hold night services, and one night dey caught me mother out praying. Dey stripped her naked and tied her hands together and wid a rope tied to de handcuffs and threw one end of de rope over a limb and tied de other end to de pummel of a saddle on a horse. As me mother weighed 'bout 200, dey pulled her up so dat her toes could barely touch de ground and whipped her [104].

Patrollers couldn't legally interfere with a slave carrying a pass [105]. But patrollers would often harass Black people whom they felt to be traveling too far, or too often [106]. Moses Grandy, a former slave, verified that the law did little to restrain the patrollers:

If a negro has given offense to the patrol, even by so innocent a matter as dressing tidily to go to a place of worship, he will be seized by one of them, and another will tear up his pass; while one is flogging him, the others will look another way; so when he or his master makes complaint of his having been beaten without cause, and he points out the person who did it, the others will swear they s aw no one beat him [107].

Other abuses were also common. Black women faced sexual abuse at the hands of patrollers, both when they were found on the road and during searches of their homes [108]. Patrollers sometimes kidnapped free Black people and sold them as slaves [109]. They also frequently threatened Black people with mutilation, sometimes with a basis in law: between 1712 and 1740, South Carolina law required escalating tortures for captured runaways, from slitting the nose to severing one foot [110].

Masters sometimes complained about the abuses directed against the slaves, but courts were generally reluctant to award damages or discipline the patrollers, for fear of undermining the patrol system [111]. The main restraint on the actions of patrollers was the economic value of the slave's life; slaves were rarely killed, since the local government would then have to compensate the owner [112]. In general, however, the patrols were invested with vast authority and wide discretion, as a North Carolina court explained in 1845:

[Patrols] partake of a judicial or quasi-judicial and executive character. Judicial, so far as deciding upon each case of a slave taken up by them; whether the law has been violated by him or not, and adjudging the punishment to be inflicted. Is he off his master's plantation without a proper permit or pass? Of this the patrol must judge and decide. If punishment is to be inflicted, they must adjudge, decide, as to the question: five stripes may in some cases be sufficient, while others may demand the full penalty of the law [113].

To summarize, the state control of slave behavior advanced through three stages. First, legislation was passed restricting the activities of slaves. Second, this legislation was supplemented with requirements that every White man enforce its demands. Third, over time this system of enforcement gradually came to be regulated, either by the militia or by the courts. The transition between these second and third steps was a slow one. Each colony tried to cope with the unreliable nature of private enforcement, first by applying rewards and penalties, and later by appointing particular individuals to take on the duty. Volunteerism was eventually replaced with community-sanctioned authority in the form of the slave patrols. Among the factors determining the rate of this transition, and the eventual shape of the patrols, were the date of settlement, the size of the slave population, the size of the White population, threats of revolt, geography, and population density [114]. As this suggests, slave patrols developed differently in the cities than in the countryside.

City Guards

Slave control was no less a priority for White urbanites than for their country kin. The growing numbers of Black people in cities were of obvious concern to the White population, and their concentration in distinct neighborhoods presented an unnerving reminder of the possibility of revolt.

In many respects, the cities followed the lead of the plantations. There, too, Black people - slaves especially, but free Black people as well - were singled out by the law, and specialized enforcement mechanisms arose to ensure compliance. These agencies "went by a variety of names, including town guard, city patrol, or night police, although their duties were the same: to prevent slave gatherings and cut down on urban crime [115]."

In the initial stage, enforcement would be entrusted to private individuals and the existing watch, but after some period the town might petition the legislature for the funds to form a permanent patrol, with the same group on duty each night [116]. The urban patrols, then, did not evolve from the watch system; rather, adapted from the rural slave patrols, they came to supplant the watchmen. Charleston formed a City Guard in 1783. It wore uniforms, carried muskets and swords, and maintained a substantial mounted division. Unlike the watchmen, who walked their beats individually, the City Guard patrolled as a company [117].

Louis Tasistro, who traveled through Charleston in the 1840s, described the patrol: "the city suddenly assumes the appearance of a great military garrison, and all the principal streets become forthwith alive with patrolling parties of twenties and thirties, headed by fife and drum, conveying the idea of a general siege [118]." A few years later, in the early 1850s, J. Benwell, an English visitor to Charleston, described the reaction of Black people to the mounting of the guard: "It was a stirring scene, when the drums beat at the Guardhouse in the public square ... to witness the negroes scouring the streets in all directions, to get to their places of abode, many of them in great trepidation, uttering ejaculations of terror as they ran [119]."

Throughout the first part of the nineteenth century, similar urban patrols were created in Savannah, Mobile, and Richmond. The Savannah guard carried muskets and wore uniforms as early as 1796. It was later equipped with horses and pistols [120]. Richmond's Public Guard was formed in 1800, after the discovery of a planned rebellion. It was assigned to protect public buildings from insurrections, and was made responsible for punishing any slaves it found out after curfew [121].

The urban patrols, and the laws they enforced, were modeled on the system developed for the plantations. But cities with developing industries had different needs than did the surrounding rural areas, with their plantation economies. For one thing, the large numbers of Black people present in the city often lived in one part of town, away from their masters, making it impossible to maintain the sort of intimate knowledge of the slave's comings and goings essential to the plantation system. Furthermore, rigid restrictions on daily travel were not even desirable. proving inconvenient for the budding industries [122]. As burgeoning industries sought out cheap sources of labor, the practice of "hiring out" slaves became increasingly common. Under this arrangement, slaves paid the master a stipulated fee, and were then free to take other jobs at wages [123]. The regulations on travel, then, had to be more flexible for slaves to do their work [124].

As the masters "capitalize[d] their slaves [125]," the bondsmen became, literally, wage slaves. Industrialization in Southern cities thus not only created new demands for social control, but threatened to alter the entire institution of slavery.

The slavery system was based essentially on the agricultural regime and no other. Its system of control was fixed on the basis of the slave's forever remaining a "field hand" or at best remaining attached to the plantation. But the city had other work for the slave to do which rendered the original plan of regulation cumbersome and unsuitable [126].

Given the White population's preoccupation with controlling Black people, the practice of hiring out slaves was quite controversial. As late as 1858 it was denounced in a grand jury "Report of Colored Population." Spelling out the concerns of the White community, the report states:

The evil lies in the breaking down of the relation between master and slave-the removal of the slave from the master's discipline and control and the assumption of freedom and independence on the part of the slave, the idleness, disorder and crime which are consequential, and the necessity thereby created for additional police regulations to keep them in subjection and order, and the trouble and expense they involve [127].

In other words, economic changes related to industrialization and urban life relaxed the master's personal control over the slave but did not reduce the racist obsession with slave control. Additional responsibilities thus fell to the state.

Between 1712 and 1822 South Carolina banned the practice of hiring out slaves, but these laws went almost entirely unenforced, and other means of control emerged [128]. Beginning in 1804, Charleston established a nightly curfew for the Black population - free and slave alike [129]. A few years later a statewide nine o'clock curfew was established. Free Black people were required to carry a pass from their employers, and patrols beat those who didn't have their "free papers [130]." A stricter law was passed in Pendleton in 1835, instructing the patrol to "apprehend and correct all slaves and free persons of color" on the streets after nine at night, "whether such slave or free person of color have a pass or not [131]."

In Charleston the law requiring passes gradually gave way to a system of badges for slaves being hired out. This procedure allowed the state the opportunity to regulate the practice of hiring out slaves, and entitled it to a share of the master's fee (that is, really, of the slave's wages) [132]. Slowly, Charleston began to pre-figure the segregated South of the twentieth century: in 1848, the city limited the right of Black people to use the public parks; in 1850, Black people were banned from bars altogether [133].

Meanwhile, throughout South Carolina, town after town asked the state legislature to transfer control of the slave patrols from the county courts or state militia to the local government. Camden won that power in 1818. Columbia followed in 1823 [134]. Georgetown requested it in 1810, but was not granted it until 1829 [135]. Ten years later, the legislature granted all incorporated South Carolina towns the power to regulate patrol duty [136].

The patrols' work was not always popular. Peter Cutting, the head of the Georgetown Guards, soon found his house burned to the ground [137]. Around the same time "A Citizen" wrote in to the Charleston paper: "I think it is dangerous for a person to send out his slave even with a pass... [138]" But the most common complaint was that the guards did not do their jobs. Grand juries frequently cited them for "shameful neglect of patrol duty," a term covering absenteeism, drinking on duty, and patrolling in a slipshod fashion [139].

Whatever the faults of these patrols, the White citizens of the American South relied on them to alleviate their anxieties about slave rebellions. These anxieties changed with the growth of the urban population, and the patrols changed with them, eventually approaching the model of a modern police force.

Still, though they provided a transition between the militia and the police, and despite their resemblance to other functionaries responsible for slave control, the patrols represented a distinct mode of policing. While originally bound up with the militia system, the patrols served in a specialized capacity distinguishing them from the rest of the militia. Furthermore, the authority over the patrols came more and more to shift from the militia to the courts, and then to the city government, implying that patrolling was regarded as a civil rather than military activity [140].

The patrols also, in certain respects, resembled the watch. The watch, even in Northern cities. was issued specific instructions concerning the policing of the Black population. Boston, for example, instituted a curfew for Black people and Native Americans, beginning in 1703 [141]; in 1736 the watch was specifically ordered to "take up all Negro and Molatto [sic] servants, that shall be unseasonably Absent from their Masters [sic] Families, without giving sufficient reason therefore [142]." But while the watch was told to keep an eye on Black people along with numerous other potential sources for trouble, the slave patrols (and later, the City Guards) were more specialized, focusing almost exclusively on Black people. In fact, it is this racist specialization that - more than anything else - distinguished the slave patrols from other police types and accelerated their rate of development.

The reliance upon race as a defining feature of this new colonial creation reveals the singular difference that set slave patrols apart from their European antecedents. Although slave patrols also supervised the activities of free African Americans and suspicious whites who associated with slaves, the main focus of their attention fell upon slaves. Bondsmen could easily be distinguished by their race and thus became easy and immediate targets of racial brutality. As a result, the new American innovation in law enforcement during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries was the creation of racially focused law enforcement groups in the American south [143].

With this specialization came expanded powers - to search the homes of Black people, to mete out summary punishment, and to confiscate a broad range of valuables without need to demonstrate further suspicion. Moreover, their relationship to the militia meant that patrols generally carried firearms, whereas the watch did not [144].

While the slave patrols did anticipate the creation of modern police, it must still be remembered that they were not themselves modern police. Of the two sets of criteria listed earlier, the slave patrols satisfy those of a police endeavor: they were public, authorized (indeed, instructed) to use force, and had general enforcement powers (if only over certain segments of the population). They do not, however, seem very modern, by the second set of criteria. They were certainly not the main law enforcement body, and they usually only operated at night. Arrangements for pay and continuity of service varied by location, but they were generally no more advanced than was typical of the watch. The patrols did have citywide (and sometimes broader) jurisdiction, and they were accountable to either the militias or the courts (or later, to special committees) [145]. And perhaps more than any police force before them, the patrols had a preventive orientation. Rather than respond to slave revolts (as the militia had done), or take off after runaways (like the professional slave catchers), the patrol aimed to prevent rebellions and sometimes operated to keep the slaves from even leaving the plantation.

The slave patrol, which began as an offshoot of the militia, and came to resemble modern police, thus provides a transitional model in the development of policing. As the militia adapted to the needs of a rural, agrarian, slave society, it evolved into a new form that surpassed the original. The slave patrols, when confronted with the conditions of a proto-industrialized city (where slavery itself was facing obsolescence) underwent a similar metamorphosis.

Charleston: "Keeping Down the Niggers"

In 1671, the South Carolina's Grand Council created a watch for Charles Town, consisting of the regular constables and a rotation of six citizens. They guarded the city against fire, Indians, slave gatherings, and other signs of trouble, and detained lawbreakers until the next day [146]. The law creating the watch was renewed in 1698, with an addendum citing the increase in the Black population:

And whereas, negroes frequently absent themselves from their masters or owners [sic] houses, caballing, pilfering, stealing, and playing the rogue, at unseasonable hours of the night Bee it therefore enacted, That any Constable or his deputy, meeting with any negro or negros, belonging to Charles Town, at such unseasonable times as aforesaid, and cannot give good and satisfactory account of his business, the said constable or his deputy, is required to keep the said negro or negros in safe custody till next morning [147].

For this work, the constable was to receive a fee from the owner of the detained slaves. In 1701, the exact language of this law was repeated, though the fee was increased and the constable was further instructed to administer a severe beating [148].

In 1703, as a wartime measure, the governor established a paid watch, and added special duties related to sailors and bars. This experiment was short-lived, however, and seventeen months after its creation it was replaced with a volunteer patrol organized by the militia [149]. This organization was essentially the slave patrol. In 1721, it again merged with the militia. Its function was broadened, giving patrollers authority over a large part of the working class besides the slaves. The new law instructed patrollers

to use their utmost endeavor to prevent all caballings amongst negroes, by dispersing of them when drumming or playing, and to search all negro houses for arms or other offensive weapons; and farther, are hereby empowered to examine all White servants they shall meet with, out of their master's business, and the same (if they suspect to be runaway, or upon any ill design) to carry such servant immediately to be whipped, or punished as he shall think fit, and then send him home to his master; and also, if they meet with any idle, loose or vagrant fellow that cannot give good account of his business, shall also be hereby empowered to carry such vagrant fellow to a magistrate [150].

By 1734, this body was again removed from the militia, and was explicitly referred to as a slave police. By this time the patrollers were all armed and mounted, and were ordered to search the homes of all Black people, pursue and capture escaped slaves, and kill any slave who used a weapon against them. Until the end of the colonial period, the Parish of Saint Philip (which includes Charleston) had two separate patrols - the two largest in the state [151].

By 1785, these patrols were incorporated into the Charleston Guard and Watch. This body was responsible for arresting vagrants and other suspicious persons, preventing felonies and disturbances, and warning of fires [152]. But one guard described his job succinctly as "keeping down the niggers [153]." Indeed, slave control was the aspect of their work most emphasized by the public officials, and given highest priority by the guard itself. "With very minor differences, their orders here were a summation of those given the rural patrols in the preceding hundred years, with the major and natural exception that they did not inspect plantations [154]."

The organization of the Charleston Guard and Watch represented a significant advance in the development of policing [155]. The force contained a developed hierarchy and chain of command, consisting of a captain, a lieutenant, three corporals, fifty-eight privates, and a drummer. Each was given a gun, bayonet, rattle (for use as a signal), and uniform coat. Some acted as a standing guard; the rest were divided into two patrols - one for st. Philip's Parish, and the other for St. Michael's. The captain issued daily reports, and all the men were paid [156]. The same group patrolled every night, and discipline and morale received a level of attention unique at the time [157]."

By our earlier criteria, there can be no question that the Charleston Guard and Watch were involved in policing. They were authorized to use force, had general enforcement responsibilities, and were publicly controlled. They were also exceptionally modern. The guard was the principal law enforcement agency in Charleston, enjoyed a jurisdiction covering the entire city (and some of the surrounding countryside), served a specialized police function, and had a preventive orientation. It also established organizational continuity and paid its personnel by salary. In fact, lacking only twenty-four-hour service, the Charleston Guard and Watch may count as the first modern police department, predating the London Metropolitan Police by more than thirty years.

Charleston, being subject to the pressures of maintaining a slave system in an urban area with an industrializing economy, underwent an intense period of innovation, just around the time of the American Revolution. Its efforts to control the Black population put it in the lead in the development of modern policing. But once policing mechanisms were in place, the authorities felt little need to tamper with them. When change again appeared on the agenda - following the discovery of a plan for insurrection in 1822 - the authorities instituted reforms that had been developed previously in other cities [158]. During the intervening years, Charleston's advances were surpassed by those of another Southern city, facing similar but distinct social pressures.

New Orleans: "Barbarism," "Despotism," and "A System of Violence"

Occupying a strategic position for both economic and military uses, the city of New Orleans has changed hands numerous times. But, until the Civil War, each subsequent regime agreed on one basic principle: the utter suppression of the Black race. In succession, the French, Spanish, and American governments enacted very nearly the same set of laws for this purpose, controlling the social, economic, and political life of the Black community and regulating the work, travel, education, and living arrangements of Black people in the city. Louis XIV instituted a "Code Noir" in 1685, which Sieur de Bienville, the founder of the French colony of Louisiana, copied; the Spanish retained it as their own while they controlled the city; and the Americans re-enacted it as the "Black Code [159]."

In 1804, as the Black population nearly equaled that of the White [160], New Orleans sought out special mechanisms for enforcing these laws. At the time, two separate night patrols were in effect - a militia guard, to protect against outside attack, and a watch, called the "seranos," whose primary duty was lighting the street lamps. But in 1804 the militia organized a mounted patrol specifically to enforce the Black Codes [161]. This unit only survived a few months, however. After repeated conflicts between the English-speaking militia guard and the French-speaking army, the patrol was disbanded in 1805, replaced with the Gendarmerie.

The Gendarmerie, while nominally a military unit, functioned more as a slave patrol than anything else. The law establishing it made this clear:

They will make rounds in suspected places where slaves can congregate, particularly on Sundays. They will break up these assemblies, foresee and prevent uproars and gambling, and declare confiscated all moneys found for their own profit.... The officers accompanied by all or part of their troop, and equipped with orders from the mayor, shall search negro huts on plantations, but only after looking for and then notifying the overseer or owner of their actions, as well as inviting them to be present at the search. And all fire-arms, lances, swords, etc. that shall be found in the said cabins will be confiscated and deposited in the City arsenal [162].

The Gendarmerie also arrested slaves traveling without passes and maintained a reserve of officers for daytime emergencies [163].

While drawn from the military, this group was directed by the mayor, magistrates, and other civil officials, and was paid through a combination of salaries, fees, and rewards. Half mounted, half on foot, and all wearing blue uniforms, the same men patrolled every night [164]. In many respects, then, the New Orleans patrol closely resembled the Charleston Guard of the same period, but it survived only briefly. In February 1806 the city council abolished the Gendarmerie, citing the cost of horses and the poor quality of the men [165]. That same year, the council created a City Guard, modeled after and performing the same functions as the Gendarmerie, though less militaristic in demeanor and lacking the horses [166]. Aside from two years when there was no patrol, this body survived until 1836 [167].

In the 1830s the City Guard came under attack in the newspapers, courtrooms, and among politicians. In 1834, the Louisiana Advertiser accused the police of "barbarism" and "despotism." It urged the city council to

dispense with the sword and pistol, the musket and bayonet, in our civil administration of republican laws, and adopt or create a system more congenial to our feelings, to the opinions and interests of a free and prosperous people, and more in accordance with the spirit of the age we live in [168].

That same year a committee of the city council decried the Guard's violent treatment of suspects, saying that "the moment they lay hands on a prisoner they at once commence a system of violence towards him [169]." It was police violence, the committee argued, that caused the forceful resistance of both prisoners and passers-by acting from "just indignation [170]."

In 1830, the death of the first person killed by a New Orleans cop prompted much of the criticism [171], but an underlying xenophobia was also at work, and the native-born population openly expressed distaste for the immigrant-dominated Guard. Another important demographic shift may also help explain this backlash against the Guard: during the 1830s and 1840s the White population increased by 180 percent, while the Black population increased at a much slower rate (41 percent) [172]. Hence, with White people in the overwhelming majority, fears of a slave revolt were less present, while ethnic tensions among White groups were increasingly pronounced. "A military-style police to protect against the danger of slave rebellion no longer compensated for the day-to-day irritation of respectable citizens who found their increasingly alien policemen too menacing and too lacking in deference [171]." In short, both the initial militarization, and eventual de-militarization of New Orleans' police were the product of the ethnic fears of the city's ruling class.

In 1836, the city council did away with the military model of policing. In its place they put a system of twenty-four-hour patrolling along distinct beats. The blue uniforms were replaced with numbered leather caps like those worn by watchmen in other cities. A Committee of Vigilance was elected to supervise them. This revision brought New Orleans into line with the watch system as it existed in Northern cities, and represented a substantial break from the Charleston model [174]. Still, the new organization retained the most modern features of the City Guard, and added to them 24-hour service. Hence, in 1836, the New Orleans city government approved the adoption of a public body, accountable to a central authority, authorized to use force, and assigned general law enforcement duties. This body would be the main agency of law enforcement, with citywide jurisdiction, organizational continuity, a specialized policing function, and twenty-four hour operations. And, as its inheritance from the slave patrol, it would be oriented toward the prevention of various disorders. In short, it would have all the major features of a modern police department [175]. As luck would have it, however, this organization never materialized.

As the city government was busy redesigning the police services, the state government was redesigning the entire municipal administration. In March 1836, the Louisiana state legislature divided New Orleans along the borders of its ethnic neighborhoods, creating three distinct municipalities, and preventing the just-settled police reforms from taking effect. Motivated by ethnic and economic rivalries, the plan maintained a common mayor and Grand Council, but divided the administration of services - including the police - into three districts. The city stayed so divided until 1852 [176].

Each department adopted a new, non-military approach, and retained some features of the old City Guard - namely, its public character, its authority to use force, its general law-enforcement duties, twenty-four-hour patrols, the goal of organizational continuity, its specialized police function, and its preventive orientation. However, none of the three could be counted as the chief law enforcement agency in the city because none had citywide jurisdiction. Furthermore, while in theory each police force was accountable to the General Council, in practice they were solely controlled by the district government and little effort was made to coordinate among them [177].

The General Council met only once each year, leaving the practical management of the city's affairs to municipal councils [178]. This arrangement actually exacerbated the ethnic tensions that led to the city's division in the first place, and neighborhood rivalries now found official expression in the structure of government [179]. In effect, the two sets of changes - fragmentation of the city government and re-structuring of the police - laid the groundwork for the development of neighborhood-based and ethnocentric political machines, with the police taking a central role.

During the 1840s and early 1850s control of the police force had become an increasingly important issue in municipal politics because of its value as a source of patronage and its influence in elections. After the restoration of unitary government in the city in 1852, the police played an even larger role in the manipulation of elections and resorted more frequently to intimidation and violence [180].

Even after formal consolidation in 1852, the police functioned as separate, district based organizations, controlled more by local political bosses than the general city government [181].

The machines' influence was palpable. For example, when the American Party (the "Know-Nothings") gained control of the city in March 1855, they immediately removed all immigrants from the police force, reducing it from 450 to 265 members [182]. After that, the police stood aside while Know-Nothings prevented immigrants from voting, and sometimes aided in the effort [183]. Opposition parties likewise fought for control of the polls. In the election of June 1858, a Vigilance Committee seized the state arsenal and police headquarters, with the stated purpose of ensuring a fair election [184]. Similar actions were taken in 1888 by the Young Men's Democratic Club, who - armed with rifles - surrounded the polls to prevent Know-Nothings and police from interfering with Democratic party voters [185].

Corruption didn't end at the polls. Less politically driven misconduct was also common. Naturally, vice laws created opportunities for corruption at all levels, and throughout the nineteenth century scandals were common. In 1854, a new chief, William James, began a vigorous campaign to enforce the laws against gambling, liquor, and other vice crimes. As his reward, the Board of Police fired him and eliminated his office [186].

Meanwhile, though state law forbade carrying concealed weapons and made no exception for police, many cops did begin carrying guns, especially revolvers, illicitly. This practice was condoned and sometimes advocated by super visors, and eventually gained the mayor's approval as well. Predictably, a lack of training led to numerous accidents, often with police casualties [187].

Brutality and violence were also common, and during the 1850s several New Orleans cops were tried for murder. Most of these cases involved personal disputes, and the victims were frequently cops themselves [188].

Less severe episodes of violence were legion. In a sample of cases covering a twenty-one-month period during 1854-1856, the Board of Police adjudicated forty-three cases of assault, assault and battery, or brutality by policemen, dismissing thirteen of the accused from the force and penalizing nine others with fines or loss of rank [189].

Of course it is still worth noting that, of the 672 cases adjudicated by the Board of Police during this same period, the majority of them - 59.2 percent - dealt with the dereliction of duty. Abuses of authority came at a distant second, comprising 17.4 percent of the cases [190].

Ironically, both sorts of complaints may have resulted from the same features of the job. Lack of discipline was certainly a factor of each. But the complaints may also reflect public disagreement about what it was the police were supposed to be doing. Respectable middle-class Protestants and temperance crusaders were eager to have the police enforce laws regulating gambling, prostitution, drinking, and other vice and public order offenses. The lower-class and immigrant communities, who often enjoyed these activities, were apt to feel that the police were intruding where they weren't wanted or needed. The poor complained that they were treated unfairly or with unnecessary force; the respectable classes felt that the police weren't doing their jobs so long as such vice persisted. This dispute directly reflects the struggle for control over the municipal government, and in a different sense, the debate about the nature of democracy - neither of which was resolved in the nineteenth century.

New Orleans, in a sense, made the transition from Southern plantation politics to Northern machine politics, with the police occupying a central role in the process. Indeed, this transition was in many respects aided by the simultaneous shift from a distinctly Southern model of policing (based on the slave patrol) to a Northern style (resembling the watch).

The most distinctive features of early southern police forces were uniforms, formidable weapons, and wages (rather than fees or compulsory unpaid service); around-the-clock patrolling and unification of day and night forces came later. In the 1840s and 1850s northern cities adopted the twenty-four-hour patrol, organizational unity, and wages for patrolmen; uniforms and fire-arms followed later (often northern policemen armed themselves with guns without official authorization or even against the law). New Orleans participated in both types of reform, adopting the southern model in the period 1805-1836 and shifting to the northern model in the years 1836-1854 (191).

This shift was significant, but not absolute; as a result, New Orleans foreshadowed many of the qualities of the modern police - qualities that finally crystallized in New York in 1848.

New York: "Almost Every Conceivable Crime"

In New York, as in New Orleans, the move toward modern policing was closely tied to the reconstitution of city government. In 1830 the state legislature divided the city's common council into a board of aldermen and a board of assistant aldermen, each elected annually by ward. Distinct executive departments were formed, and the mayor was assigned the responsibility to see that the laws were enforced. A year later, the council gave him some of the authority he needed to meet that demand, putting him at the head of the watch [192].

In the spring of 1843, Mayor Richard H. Morris proposed another round of reforms designed to reorganize the city government and consolidate the police. The state legislature authorized the city to create and manage a single, centralized police department - specifically a "Day and Night Police" consisting of 800 officers. Under this plan, each ward would have its own patrol, and the officers had to live in the wards where they worked. The councilors would nominate officers from their ward, and the mayor would appoint them. This plan was finally accepted in May 1845 [193].

The new police ranked as extremely modern by the criteria listed earlier: a single organization was entrusted with the exclusive responsibility for law enforcement, served a specialized police function, patrolled twenty-four hours a day, and employed salaried personnel [194]. In fact, New York City is often credited with having the first modern department in the United States. As we've seen, its claim to this title is debatable. The Day and Night Police marked a step forward in a nationwide progression, drawing from and solidifying ideas already in circulation elsewhere. But if New York's police did not invent the model, they set the standard for the rest of the country. At the same time, they also set a new standard for political interference.